Most culturally literate Americans would agree that the Declaration of Independence is a basic expression of American ideals and that high school graduates should understand, in a general way, the circumstances in which it was written, the principles it articulates, and the influence it has had in the nearly 250 years since it was adopted.

The education standards of nearly every state require teachers to teach and pupils to learn about the Declaration of Independence. The problem with most of these standards is that they don’t say, with sufficient clarity, what teachers are expected to teach about the Declaration.

The New York standards, for example, direct teachers to address the Declaration in elementary, middle school, and high school as an expression of “American democratic values and beliefs.” The associated framework for high school says that “students will examine the purpose of and the ideas contained in the Declaration of Independence,” mentioning the Declaration of Independence just this once.

This vague guidance opens the door to pernicious nonsense like the claim — advanced by journalist Nicole Hannah-Jones in her “1619 Project” — that Congress declared independence to protect American slaveholders from the threat of British abolitionism. Never mind that the premise is false. There were a few opponents of slavery in Britain in 1776, as there were in America, but no abolitionist movement. Britain abolished slavery in its empire in 1834 — fifty-eight years after American independence — thanks to the trans-Atlantic abolitionist movement inspired by the American Revolution. Ms. Hannah-Jones gets the Revolution backward, presenting it as a source of oppression in American life when it is actually the source of freedom.

The New York State Education Department nonetheless lists the “1619 Project Curriculum” among just fourteen “Teacher Resources” that “promote standards-based instruction for all New York State students.” The department adds that it doesn’t endorse the resources on this highly selective list, but that seems more than a little disingenuous. In New York a teacher can address the Declaration as an expression of “American democratic values and beliefs” by retailing the false claim that the Declaration failed to promote democratic values and beliefs.

In fact the Declaration has little to say about democracy but much to say about popular sovereignty, the foundation of our democratic values and institutions. The Declaration of Independence is also the most important expression of the fundamental ideals that have defined our national identity for 250 years: independence, liberty, equality, natural and civil rights, and responsible citizenship.

While the largest part of the Declaration was devoted to a list of the “Injuries and Usurpations” George III had visited on the colonies in the recent past, the most important parts were entirely forward looking — a declaration that Americans constituted “one people,” that this new nation would assume a “separate and equal station” among “the Powers of the Earth,” and that the nation would be dedicated to ideals of universal equality and natural rights. The consequences of these commitments for government and for the lives of ordinary Americans all had to be worked out. Thomas Jefferson, who wrote the Declaration in the quiet of a rented room over the last three weeks of June 1776, understood this. So did the men who subscribed their names to the Declaration. They mutually pledged their lives, their fortunes, and their honor to the principles it expressed.1

The Declaration of Independence was, in the summer of 1776, a radical, revolutionary manifesto of national purpose. It remains so. If we are going to educate young Americans about what it means to be an American, we have to get this right.

One People

The Declaration of Independence is a proverbial classic — something everyone has heard of but few people read. Even fewer read it carefully, though no document offers careful readers more insights about the ideals that have shaped our history.

The first part of the Declaration explained that the purpose of the document was to express to the world why the colonies had severed their connection with Britain:

When in the Course of human Events, it becomes necessary for one People to dissolve the Political Bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the Powers of the Earth, the separate and equal Station to which the Laws of Nature and Nature’s God entitle them, a Decent Respect to the Opinions of Mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to that Separation.

The phrase “Laws of Nature and Nature’s God” locates the Declaration in the Enlightenment, that remarkable movement to reconcile the insights of the scientific revolution, driven by Newton’s understanding of the immutable laws governing the natural world, with the omnipotence of God as revealed in Scripture. There can be no mistaking this: the Declaration places God before nature — there are natural laws but they are the creation of God, as is nature itself. The Declaration is not troubled by the conflict so many modern people find between natural science and revealed religion. It enlists both in cause of freedom, defying the claims of kings to rule by divine ordination.

Jefferson packed several assumptions into this opening sentence. The first was that the colonists were “one People,” which was not yet true. The colonists still identified very closely with their colonies, and the idea that they constituted a nation in the sense that Englishmen or Frenchmen belonged to a single nation had barely occurred to anyone. The colonists were loosely tied by a common language, though many recent arrivals — particularly the Germans who had been pouring into the middle colonies for a generation — spoke little English. They were nearly all Christians and overwhelmingly Protestant, but they belonged to many Protestant denominations and sects, some of which were mutually antagonistic. The colonists were scattered from the subtropical lowlands of coastal Georgia to the mountain valleys of New England, a vast expanse of territory that was in no sense a single land.

The thing that most closely bound them together — common allegiance to the British Crown — they were in the act of discarding. But perceptive leaders understood that the shared experience of resistance and war was binding the colonists together in a new way. Americans may not have been one people in 1776, but shared principles and the shared experience of a war that would last for eight years and touch every part of the new nation would make them one people, with common ideals, shared history, heroes, and symbols. In time the Declaration of Independence itself would become a part of that national identity and its draftsman, Thomas Jefferson, would be recognized as one of the central figures in our national history.2

The Powers of the Earth

Jefferson’s second assumption was that other peoples constituted “the Powers of the Earth,” distinguished by their “separate and equal station” in the world. This was true but did not describe the global situation in a comprehensive way, as Jefferson and his peers understood. The world that they knew was dominated by a small group of great powers, among which Britain, France, Spain, Austria, and Russia predominated, to which might be added minor powers including Holland, Prussia, and Sweden.3

The great powers were, in varying ways, imperial powers that exercised dominion over large areas of the globe and over peoples who enjoyed few rights. Most of their peoples were subjects who were either exploited or ignored by the powers that dominated them. The united colonies had no intention of being dominated. The Declaration expressed the bold intention to assume a separate and equal place among “the Powers of the Earth.”

The extraordinary nature of this intention is easily lost on us, because our world is divided into hundreds of independent, sovereign states, each in principle separate from and equal to all the others. The modern United Nations, an assembly of the world’s sovereign states, has 193 members. Most of them are, in reality, too small or too weak, economically or militarily, to be wholly independent of the modern great powers, but nearly all of them maintain sovereign authority over their territory — they have governing bodies that make laws, institutions to enforce those laws, exert at least some control over their boundaries, and engage in relations with other sovereign states.

The eighteenth-century world was not divided in this way into separate and equal sovereign states. Much of the world was still occupied by indigenous peoples for whom the concept of sovereign statehood had no meaning, or as in much of North America, indigenous peoples who had a sense of identity, belonging, place, and subordination to custom and tradition that was comparable, but far from identical, to the European idea of sovereign statehood.

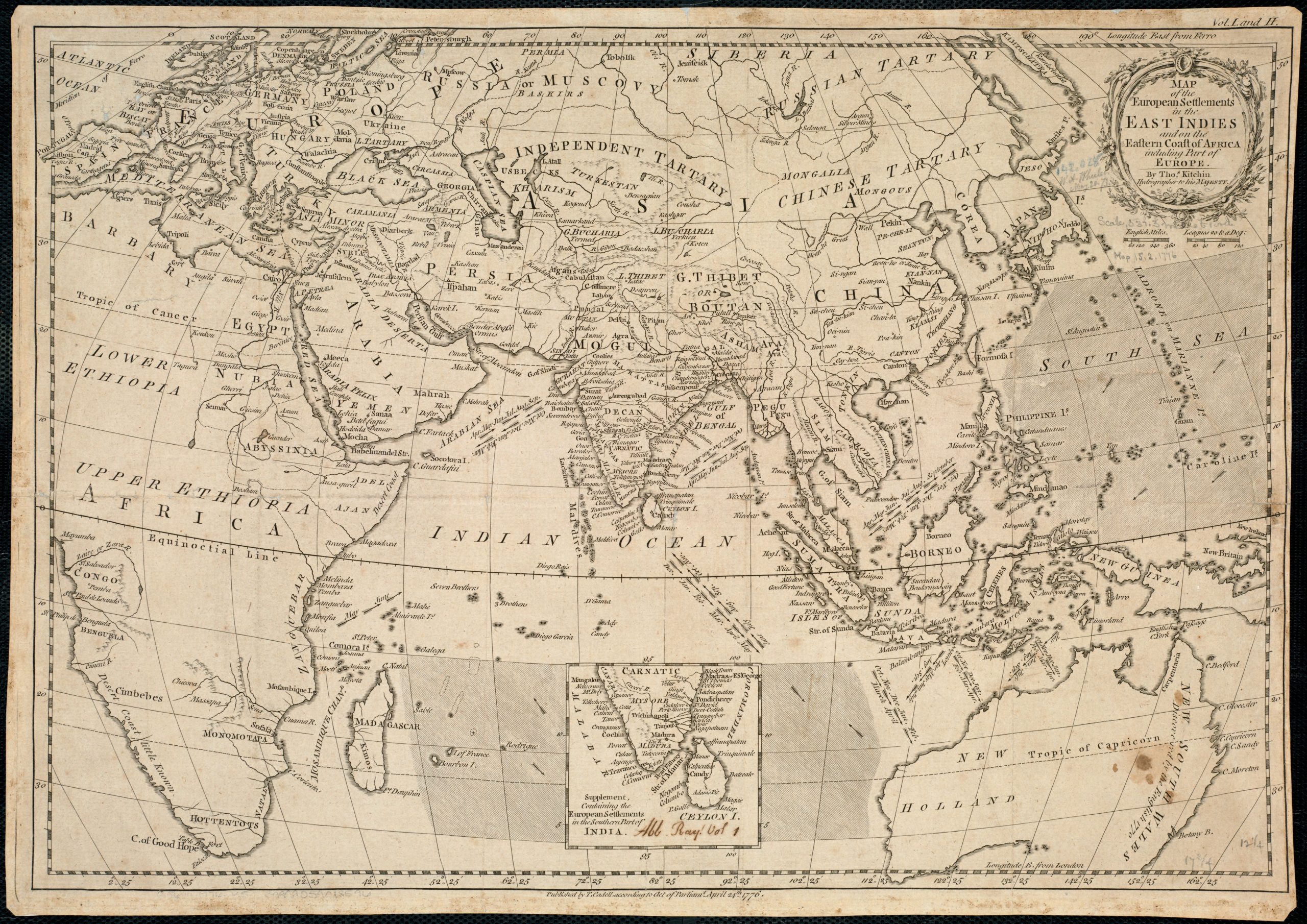

The empires of the European powers were growing even as Americans were fighting the first successful war of liberation against colonial domination. This British map of the Eastern Hemisphere, published within months of the Declaration of Independence, reflects Britain’s vast imperial ambitions. Courtesy Boston Public Library

Much of Europe, including most of what we know as Germany, still consisted of semi-feudal fiefdoms, some of them separate from others but many of them subordinate to or dependent on some imperial power in a way that compromised their equality with the fully independent states. The same was true of much of Asia and Africa, which were home to monarchical states of varying independence, ranging from the vast but diffuse authority of the “Celestial Empire” of the Chinese emperors to the dependent kingdoms and vassal states spread across the Eastern Hemisphere. The leaders of the American Revolution had no intention of creating a client state dependent on any of the great powers.

The idea of creating a new, independent, sovereign state was unprecedented. Most of the established states, and all of the “Powers of the Earth,” were several centuries old, and each claimed to be rooted in customs and traditions reaching back to antiquity.

Creating new, independent, sovereign states was a subject of theoretical speculation for the political and legal thinkers of the Enlightenment. The most important was the Swiss jurist Emer de Vattel, whose 1758 treatise, The Law of Nations, was the standard work on international law for more than fifty years.4 “Every nation which governs itself,” Vattel wrote,

without dependency on any foreign country, is a sovereign state. Its rights are by nature the same as those of every other state. These are the moral persons who live together in a natural society subject to the law of nations. For any nation to make its entrance into this great society, it is enough that it should be truly sovereign and independent, that is to say, that it governs itself under its own authority and its own laws.

Jefferson and most of the other leaders in the Continental Congress were intimately familiar with Vattel’s work. Those who were not could refer to the copy presented to Congress by Benjamin Franklin, who wrote to Vattel’s English editor in December 1775 that the book “has been continually in the hands of the members of our congress.”5 The United States was the first new state established in the world on the basis of sovereign independence as Vattel defined it. What Vattel imagined, Americans created. America is free because they did so.

Popular Sovereignty

For thousands of years, monarchs had ruled the peoples of the world. Although those monarchs, from the pharaohs of Egypt to the emperors of China, varied considerably, nearly all of them claimed their right to rule was ordained by divine power. In Britain, reverence for the divine nature of royal authority had eroded in the seventeenth century, when Parliament tried and executed one king and drove a second into exile, then limited the authority of his hand-picked successor with a bill of rights that assured that the king would share governing authority with Parliament. King George III nonetheless claimed to rule over his empire “by the Grace of God,” and anyone who challenged that authority risked arrest, trial, and execution for treason.

The delegates who signed the Declaration of Independence took that risk. The longest part of their Declaration listed the “repeated Injuries and Usurpations” committed by the king, charging that he had blocked legislation, interfered with their assemblies, discouraged immigration, deprived colonists of due process, and sent a standing army to the colonies to impose his will. He had, they said, “plundered our Seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our Towns, and destroyed the Lives of our People,” and was in the process of sending foreign mercenaries to complete “the Works of Death, Desolation and Tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty and Perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous Ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized Nation.” He was a tyrant, Congress concluded “unfit to be the ruler of a free people,” and had forfeited the allegiance of the colonies, which would henceforth be “Free and Independent States.”

In our age of unfettered expression, when severe criticism of government officials is published every day, the boldness of these charges may be hard to grasp. Nothing quite like it had ever been published. But the charges leveled at the king were modest compared to the extraordinary claim the Declaration makes about the source of government power.

The Declaration of Independence claims that the authority to govern is derived “from the Consent of the Governed.” Like many of the ideas in the Declaration, this one had been proposed and discussed by political thinkers for generations before the American Revolution. The idea was common among radical thinkers in Britain during the English Civil War of the 1640s that resulted in the overthrow and execution of King Charles I. John Locke explained in his Second Treatise of Government, published in 1690, that the “liberty of man, in society, is to be under no other legislative power, but that established, by consent, in the commonwealth; nor under the dominion of any will, or restraint of any law, but what that legislative shall enact, according to the trust put in it.”6

Locke and others appealed to the idea that sovereignty originates with the people to justify the English Glorious Revolution of 1688, in which King James II was driven from the throne and the sovereign power of the monarchy transferred to William of Orange and his wife, Mary. They claimed popular sovereignty as the ultimate foundation of royal sovereignty, not as a power to replace monarchy with a new form of government.

Today we take it for granted that the authority of government is based on the consent of the people, and that acting together a people can change their form of government, but in 1776 this was a radical idea.7 The Declaration makes this claim in its most familiar passage:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these Rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just Powers from the Consent of the Governed, that whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these Ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and institute new Government, laying its Foundation on such Principles and organizing its Powers in such Form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

The Declaration based the right of the people to abolish or alter their government on what it claimed was the self-evident truth that “all Men are created equal” and possess “unalienable rights.” European philosophers and political radicals had been speculating about universal equality and universal natural rights for decades, but the American Revolutionaries were the first people in modern times to base a system of government on the principle of universal equality and to define the purpose of government as promoting and defending the rights of a sovereign people to “Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness.”

Whatever else they were in 1776, those truths were not self-evident, at least in the sense that they were truths any rational person then living would acknowledge. They were declared in darkness, in a world where equality was almost unknown and the rights we cherish were barely recognized. It was a world where daily experience suggested that the mass of mankind was made to suffer without recourse, without rights, the lives of ordinary people held cheap by men who claimed that the right to rule and to high status and wealth was a birthright of the few, whom the many were created to serve. The darkness of that world was too great to be dispelled in one movement, or even a few decades. Reforming it has been the work of many generations, and its heroes — men and women of all races — are the common creators of free society.8

Unalienable Rights

The Declaration refers to unalienable rights — rights that cannot be sold, given away, or taken away. We would be more likely to call these natural rights or human rights. They include the basic rights inherent in the human condition. They are not granted by government and do not depend on government for their existence. They are based on what the Declaration calls the “Laws of Nature and Nature’s God.”

The Declaration lists life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness among these natural rights. The right to life is the most fundamental, implying, at the very least, that every person has a right to defend himself or herself against aggression and to provide for their own basic needs.

Liberty is the absence of restraint or interference, including interference in what people choose for themselves as long as those choices do not endanger the lives or compromise the rights of others to make choices for themselves. Thus the rights of conscience — to make personal judgements, especially about matters of faith, morality, and ethics — are natural rights. So are the choices people make about religion and their expression in practice, as long as those practices do not endanger the lives or comparable rights of others. Likewise the right to express our judgments is also a natural right.

The third natural right named in the Declaration is the pursuit of happiness. This phrase seems odd to many modern readers because happiness now refers mainly to personal satisfaction or pleasure, often of a short-lived kind. In the eighteenth century, happiness included satisfaction and pleasure but it also included something richer and more complicated. It also referred to the sense of personal fulfillment achieved by virtuous deeds — sacrificing private gain and setting aside selfish motives for the good of other people.9

The right to pursue happiness was thus a right to seek fulfillment by doing good for others, or what people in the eighteenth century called benevolence. By doing so an individual could secure for himself or herself dignity, respect, appreciation, honor, fellowship, community, and love. We do not need these things to be free — that is, to live and exercise our liberty — but we need them to be truly happy.10

In writing this passage of the Declaration, Jefferson could have followed John Locke’s assertion that our rights to life, liberty, and property are the most fundamental. Some historians contend that Jefferson substituted pursuit of happiness for property, or even that possessing property is an essential aspect of happiness, and so is embraced by pursuit of happiness. It seems just as plausible to conclude that Jefferson left the right to property out, remembering that the Declaration says that life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness are “among” our unalienable rights, implying that there are others. Our right to possess property is certainly among those other natural rights.

The catalogue of the king’s “abuses and usurpations” that makes up the largest part of Declaration documents the British government’s violations of the political or civil rights of the colonists. The list is presented to justify the claim that the king had become a tyrant and thus abandoned his responsibility to defend the natural rights of his subjects.

Unlike natural rights, which exist independent of government, political or civil rights are based on the consent of the sovereign people to be bound by laws designed to protect their lives, promote their interests, and resolve their disputes. Natural rights are universal, but civil rights may differ from one political system to another. Britain’s North American colonies had long enjoyed rights to participate in making the laws, to the swift and fair administration of justice, and to freedom from excessive taxation, military occupation, and expensive, invasive government regulation. Although the Declaration of Independence did not describe the governments the independent states would form or the laws they would enact, the list of the king’s abuses reflects the civil rights the Revolutionary generation valued most highly.

Created Equal

The Declaration of Independence appealed to the principle of universal equality at a time when the natural rights of many colonist were routinely violated and when the majority, including all women, were excluded from the enjoyment of civil rights.

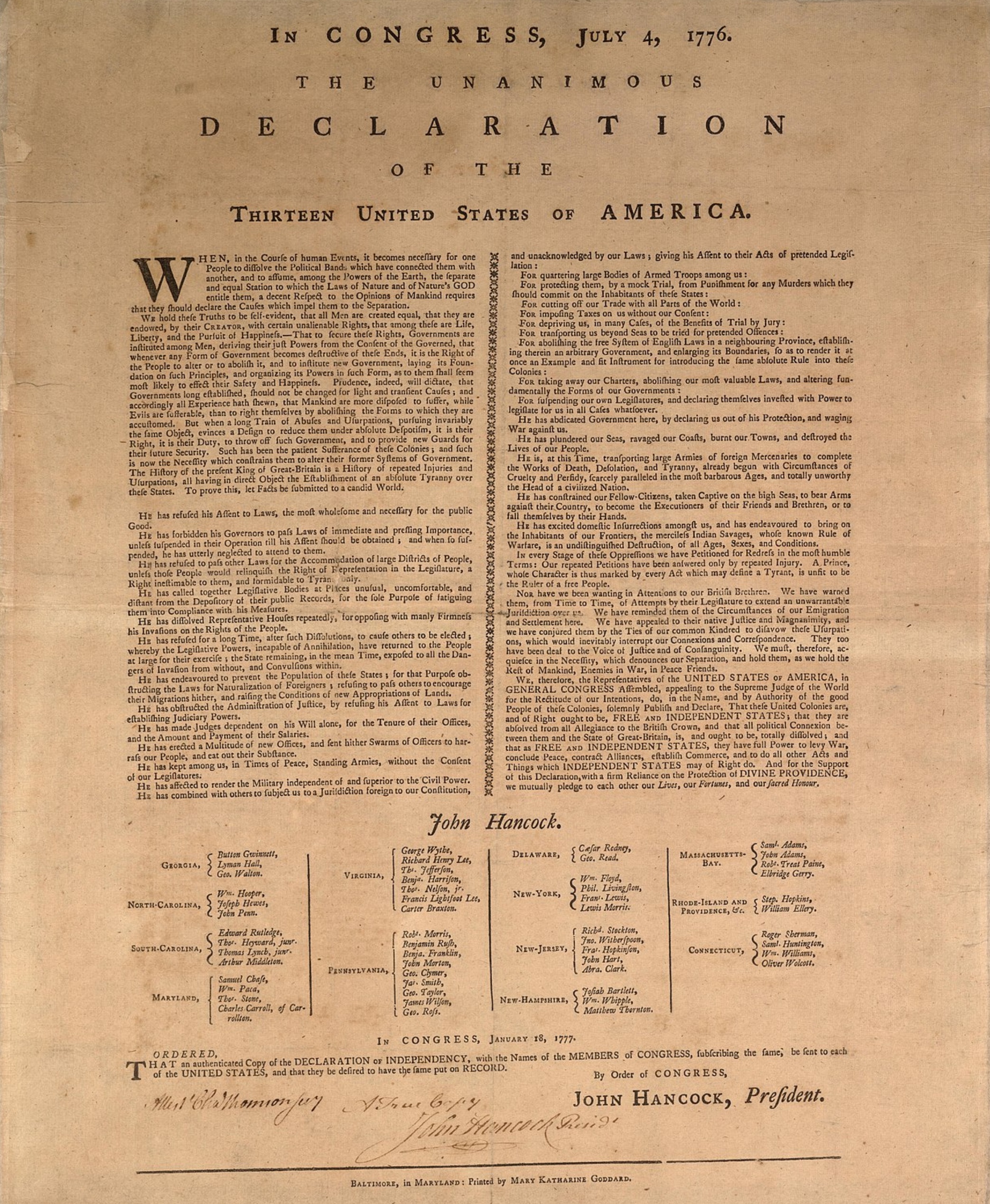

This broadside of the Declaration of Independence was the first printed version to include the names of the signers. It was published by Mary Katherine Goddard, a Baltimore printer. The Declaration’s bold assertion that “all men are created equal” has fueled claims to the same equality for women and minorities for 250 years. Library of Congress

The natural rights of enslaved Americans were ignored. The law deprived them of control over their lives and did little to protect them from attack. Killing an enslaved person was a serious crime under the laws of most of the colonies, but those laws were only rarely enforced. Indeed enslavement was maintained by violence and the threat of violence. The dehumanizing brutality of slavery sought to deprive the enslaved of independent thought and self-esteem in order to make them obedient, and their constant subordination to the will of their enslavers made personal fulfillment — the pursuit of happiness — impossible.11

The logic of the Declaration was inescapable, although many people dependent on enslavement as a source of wealth would seek to escape it: if all men were created equal and endowed with unalienable natural rights, slavery would have to be abolished and the natural rights of former slaves protected and promoted.

The only alternative was to prove that Africans and their American descendants were not men and women in the same way that the Europeans and their American descendants were — that they were naturally inferior and that their inferiority meant they did not possess natural rights. Such racist views were widely held in the eighteenth century, even by otherwise sophisticated thinkers. Scottish philosopher David Hume, who had no personal experience with Africans, thought that the races of mankind had different origins and wrote that he was “apt to suspect the Negroes, and in general all other species of men, to be naturally inferior to the whites.”12

Others like Pennsylvania abolitionist Anthony Benezet insisted that Africans and their descendants had the same natural capacities as Europeans and their descendants and possessed the same natural rights. Frances Hutcheson, the Scottish philosopher whose ideas influenced Jefferson and other American Revolutionaries, argued against slavery, insisting that there could be no “right to assume power over others, without their consent.”13

Among those who insisted that Africans and their descendants possessed natural rights were Africans themselves, including Ignatius Sancho. Born on a slave ship sailing for the Caribbean, he was later freed and became a successful London shopkeeper, writer and opponent of slavery. Sancho and others who argued for the abolition of slavery expected America to become a haven for justice and equality.14

Thoughtful people on both sides of the Atlantic recognized that talented men and women of African descent like Ignatius Sancho and Phillis Wheatley proved that people born in Africa and their descendants, enslaved and free, possessed natural abilities in the same way as Europeans and their descendants and possessed the same natural rights. Others recognized that the possession of talents had no bearing on the possession of natural rights.

Principled opposition to slavery, which had previously been expressed by a few, mostly on religious grounds, attracted support as the idea of universal natural rights took hold. The controversy between the colonies and Britain accelerated thinking on both sides of the Atlantic about natural rights and fed the early development of the antislavery movement in America and in Britain.15

People in Britain who were most uncomfortable with slavery tended to be vocal defenders of American rights and supporters of the American cause. Some of them saw the Revolution as a truly radical movement based on the natural rights of all mankind. This was the view of the English radical Richard Price, a great friend and admirer of Benjamin Franklin. Englishmen like Price who believed that governments should be based on natural rights recognized the American Revolution as a truly and deeply radical moment in world history that would ultimately transform the lives of people everywhere.

Since principled opposition to slavery rested on the idea of natural rights, it is not at all surprising that the first statute abolishing slavery ever written was adopted, not in Britain, but in what might justly be described, at that moment, as the most culturally diverse, philosophically sophisticated, and forward-looking place in the western world: Pennsylvania. With a founding creed based on Quaker ideas of moral equality, tolerance, charity, and non-violence, eighteenth-century Pennsylvania attracted settlers and religious refugees from several parts of western Europe, including people from differing cultural and legal traditions. The idea that universal equality and natural rights were the basis of government was accepted more readily there than anywhere else and led logically to the Pennsylvania Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery, adopted in 1780.

Slavery was abolished by law in the states north of Pennsylvania during the Revolutionary generation and as a direct consequence of the Revolutionary appeal to universal natural rights. Securing the adoption of those laws required, in some cases, lengthy debate and compromises resulting in gradual abolition schemes that prolonged the bondage of enslaved Americans, but which ultimately extinguished slavery in the middle states and New England.

While other Americans considered the meaning of the Declaration of Independence and debated measures to fulfill its ideals, thousands of African Americans served in the armed forces that won American independence. As many as nine thousand served in the Continental Army and Navy, in the militia, on privateering vessels, and as teamsters or servants to officers. This was about four percent of the men who served, but their terms were typically much longer than that of whites. During the latter stages of the war, when white recruitment slowed, black soldiers, sailors, and support personnel probably accounted for between fifteen and twenty percent of the effective strength of the armed forces. America is free thanks to their service.16

“Posterity will triumph”

The Declaration of Independence did not describe the independent states as they were. It reflected ambitions for what they might and should become — free republics in which natural and civil rights would be respected and citizens would devote themselves to the public good. Declaring that all men are created equal was not hypocrisy — it was an aspiration to which the delegates pledged themselves. All that their pledge implied was not clear to them.

The Declaration of Independence was a beginning. The Declaration did not make the American states independent. There remained a war to fight and win. “I am well aware of the toil and blood and treasure, that it will cost us to maintain this Declaration, and support and defend these States,” John Adams wrote home.

Declaring Americans one people did not make them so. Americans would become one people when they had a national identity, made up of shared experiences, heroes, victories, suffering, symbols, and ideals. The long war for independence supplied many of them. Generations of historical experience would supply many more.

Declaring universal equality and rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness self-evident and those rights unalienable did not immediately change the lives of the women and men for whom those rights were routinely ignored. Inequality remained the norm, and whatever rights people might possess in the imagination of philosophers, few enjoyed those rights in practice.

In the years that followed the Declaration of Independence, Americans made remarkable progress in fulfilling its high ideals. They devised state constitutions reflecting the consent of the governed — or at least those who possessed sufficient property to vote and hold public office. They created republican governments responsive to the will of the people and dedicated to their interests — governments that would become increasingly democratic in the early nineteenth century. They began the process of dismantling established religions, ensuring greater liberty of conscience than enjoyed anywhere in the world. And they began the process of dismantling slavery.

Generations of Americans would have to dedicate themselves to fulfilling the aspirations expressed in the Declaration before most Americans would enjoy their natural and civil rights. Progress has been uneven and often frustrating, slowed by complacence and timidity as well as selfishness, bigotry, and intolerance. But progress we have made, and we will continue to make.

All of this is clear in hindsight. At the time the path ahead was dark. “Yet through all the gloom,” John Adams wrote home to Abigail, “I can see the rays of ravishing light and glory. I can see that the end is more than worth all the means. And that posterity will triumph . . .”17

This essay is adapted from the author’s new book, Freedom: The Enduring Importance of the American Revolution, published by Lyons Press in October 2023. Freedom is available from independent bookstores (here’s a link to the listing at Politics and Prose in Washington, D.C.) and from online retailers, including Barnes and Noble and Amazon.

Notes

- On Jefferson’s service in Congress and the drafting of the Declaration, see Dumas Malone, Jefferson and His Time, vol. 1: Jefferson the Virginian (Boston: Little Brown and Company, 1948), 197-231, and Julian Boyd, The Declaration of Independence: the evolution of the text as shown in acsimiles of various drafts by its author, Thomas Jefferson (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1945. [↩]

- On the symbolic role of Jefferson and the Declaration in American culture, see Merrill D. Petersen, The Jefferson Image in the American Mind (New York: Oxford University Press, 1960). On the Declaration as a visual symbol of national identity, see David Hackett Fischer, Liberty and Freedom: A Visual History of America’s Founding Ideas (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 190-91, 207-8, 211-12. On the Declaration as a definition of the nation’s first principles, see Harry V. Jaffa, Crisis of the House Divided: An Interpretation of the Issues in the Lincoln-Douglas Debates (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1959). [↩]

- On the international importance of the Declaration of Independence, see David Armitage, The Declaration of Independence: A Global History (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007). On American ambitions and their fulfillment, see Eliga H. Gould, Among the Powers of the Earth: The American Revolution and the Making of a New World Empire (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012). [↩]

- Emerich de Vattel, The Law of Nations; or Principals of the Law of Nature Applied to the Conduct and Affairs of Nations and Sovereigns (2 vols., London: Printed for J. Newbery, et al., 1760) was the first English edition. It has been continuously in print since. [↩]

- Franklin to Charles-Guillaume-Frédéric Dumas, December 9, 1775, William B. Willcox, ed., The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 22: March 23, 1775-October 27, 1776 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982), 287-91. [↩]

- John Locke, Two Treatises of Government: A Critical Edition with an Introduction and Apparatus Criticus by Peter Laslett (2nd ed., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980), 301. On the influence of Locke’s moral and political ideas in the American Revolution, see Thomas L. Pangle, The Spirit of Modern Republicanism: The Moral Vision of the American Founders and the Philosophy of Locke (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988) and Michael P. Zuckert, Natural Rights and the New Republicanism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994). [↩]

- For an intriguing argument that uncertainty about the meaning and application of popular sovereignty was left unresolved by the Revolutionary generation and shaped subsequent American political and constitutional development, see Christian G. Fritz, American Sovereigns: The People and America’s Constitutional Tradition Before the Civil War (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007). [↩]

- No modern historian has challenged us to take the ideas of the Declaration more seriously than C. Bradley Thompson, whose America’s Revolutionary Mind: A Moral History of the American Revolution and the Declaration That Defined It (New York: Encounter Books, 2019) seeks to reconstruct the common philosophy he argues shaped the Declaration and the way it was understood, which he calls a “near-unified system of thought.” Professor Thompson is puzzled that the interpretation of Revolutionary political thought that emerged from the work of Bernard Bailyn, J.G.A. Pocock, Gordon Wood, and their contemporaries in the 1960s and 1970s, focused on republican ideas drawn from antiquity and filtered through Renaissance civic humanists, has remained so dominant for so long. In fact it has not. Historians of the last generation are simply not focused on formal political thought or political ideology. They are far more interested in reconstructing the experiences of ordinary people for whom formal political thought had little meaning. Those who are interested in political ideas have whittled away at the republican synthesis by exploring the wide-ranging political ideas of people other than Adams, Jefferson, Hamilton, Madison, and James Wilson. The republic synthesis has not been replaced by a new unified interpretation because today’s historians are more interested in other themes and in exploring diversity. But that hasn’t stopped Professor Thompson, who seeks, with brilliant erudition, to replace republicanism with Lockean liberalism as the way to understand the Declaration and ourselves. [↩]

- For an alternative reading — these are indeed matters about which serious people disagree — see Thompson, America’s Revolutionary Mind, 206-10, in which Professor Thompson contends that Jefferson drew “pursuits of happiness” from Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding, and that happiness for Locke is an individual pursuit, constrained only by our ability to recognize the difference between real and imaginary or ephemeral happiness. [↩]

- Jefferson may have based his ideas about the pursuit of happiness on the moral philosophy of Scottish philosopher Frances Hutcheson’s A System of Moral Philosophy (3 vols., Glasgow: Printed and Sold by R[obert] and A[ndrew] Foulis, 1755). On the influence of Hutcheson on Jefferson, see Garry Wills, Inventing America: Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1978). No study of the Declaration has been more effusively praised or more fiercely condemned. Critics found Wills’ claim that Hutcheson was more important to Jefferson’s thinking than Locke subversive as well as wrong. The debate is a splendid place to begin exploring the varied historical interpretations of the Declaration, which all the participants agree is vital to understanding our republic—hence the remarkable passion with which they approach what may seem, to laymen, like esoteric points about eighteenth-century political philosophy. To begin, see Ralph Luker, “Garry Wills and the New Debate Over the Declaration of Independence,” Virginia Quarterly Review, 56, no. 2 (Spring 1980), published online at http://www.vqronline.org/essay/garry-wills-and-new-debate-over-declaration-independence. [↩]

- Ira Berlin, The Long Emancipation: The Demise of Slavery in the United States (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015), 47-106. [↩]

- Of National Characters,” in David Hume, Essays: Moral, Political, and Literary, edited by Eugene F. Miller, Thomas Hill Green, and Thomas Hodge Grose (Indianapolis, Indiana: Liberty Fund, 1987), 629. Hume seems to have been at least somewhat more conflicted about race than this blunt passage suggests. Ins his essay “On the Populousness of Ancient Nations,” written about the same time, Hume wrote “As far . . . as observation reaches, there is no universal difference discernible in the human species.” ibid., 378. [↩]

- Frances Hutcheson, A System of Moral Philosophy (3 vols., Glasgow: Printed and Sold by R[obert] and A[ndrew] Foulis, 1755), 1: 299-300. [↩]

- Sancho’s correspondence, published as Letters of the Late Ignatius Sancho, An African. In Two Volumes. To which are prefixed, Memoirs of his Life (2 vols., London: Printed for J. Nichols, 1782) reveal a witty, determined man of high principle. Sancho abhorred American war, but wrote with anticipation about the future of American society: “When it shall please the Almighty that things shall take a better turn in America — when the conviction of their madness shall make them court peace — and the same conviction of our cruelty and injustice induce us to settle all points in equity — when that time arrives, my friend, America will be the grand patron of genius—trade and arts will flourish—and if it shall please God to spare us till that period — we will either go and try our fortunes there — or stay in Old England and talk about it.” (1: 170). [↩]

- For an authoritative treatment of the development British antislavery thought in the wake of the American Revolution, see Christopher Leslie Brown, Moral Capital: Foundations of British Abolitionism (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006). [↩]

- These estimates of African American participation in the armed forces are from Gary B. Nash, The Forgotten Fifth: African Americans in the Age of Revolution (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006). These figures may underestimate African American participation in the armed forces, since black soldiers and sailors are not easily distinguished from their white counterparts; most estimates are based on the identification of common and distinctively African American names and on muster rolls and other contemporary documents that explicitly identify soldiers and sailors as African American. Estimates based on these methods and records inevitably vary. [↩]

- John Adams to Abigail Adams, July 3, 1776, Lyman H. Butterfield, ed., Adams Family Correspondence, vol. 2: June 1776 - March 1778 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1963), 29-33. [↩]