In 1787, when James Madison was preparing for the convention that wrote our Constitution, his friend Thomas Jefferson was in Paris, wasting his time as ambassador from a government that had so little authority that the French government could safely ignore it. With little official business to do, Jefferson occupied his time corresponding with Madison and other American friends about the nature of free government and the capacity of ordinary people to govern themselves. Together they fashioned institutions that empower people around the world.

Many of Jefferson’s friends were deeply concerned about violent unrest driven by high taxes and the burden of debts compounded by deflation. In Massachusetts those toxic conditions had driven thousands of farmers to take up arms to stop debt collection, leading the state government — inexperienced, insecure, and imperious — to impose order at the point of a bayonet.

Jefferson was not deeply concerned about the unrest in Massachusetts, known then and since as Shays’ Rebellion. He agreed with Madison that the insurgents had committed “absolutely unjustifiable” acts, but he thought “they were founded in ignorance, not in wickedness.” The insurgents did not understand that their distress was the result of economic conditions the government was incapable of addressing.1

Although the people were sovereign, Jefferson wrote, they would not always be right. “The people can not be all,” he wrote, “and always, well informed.” In a government in which the people have a just degree of influence a certain amount of what Jefferson called “turbulence” was inevitable. But Jefferson was concerned that the unrest might lead reformers to conclude “that nature has formed man insusceptible of any other government but that of force, a conclusion not founded in truth, nor experience.” A government based on force — including monarchy in all its forms — was inherently unjust. “It is a government of wolves over sheep.”2

The people of the world have been governed for most of history by wolves. Jefferson had confidence in the capacity of ordinary people to govern themselves.

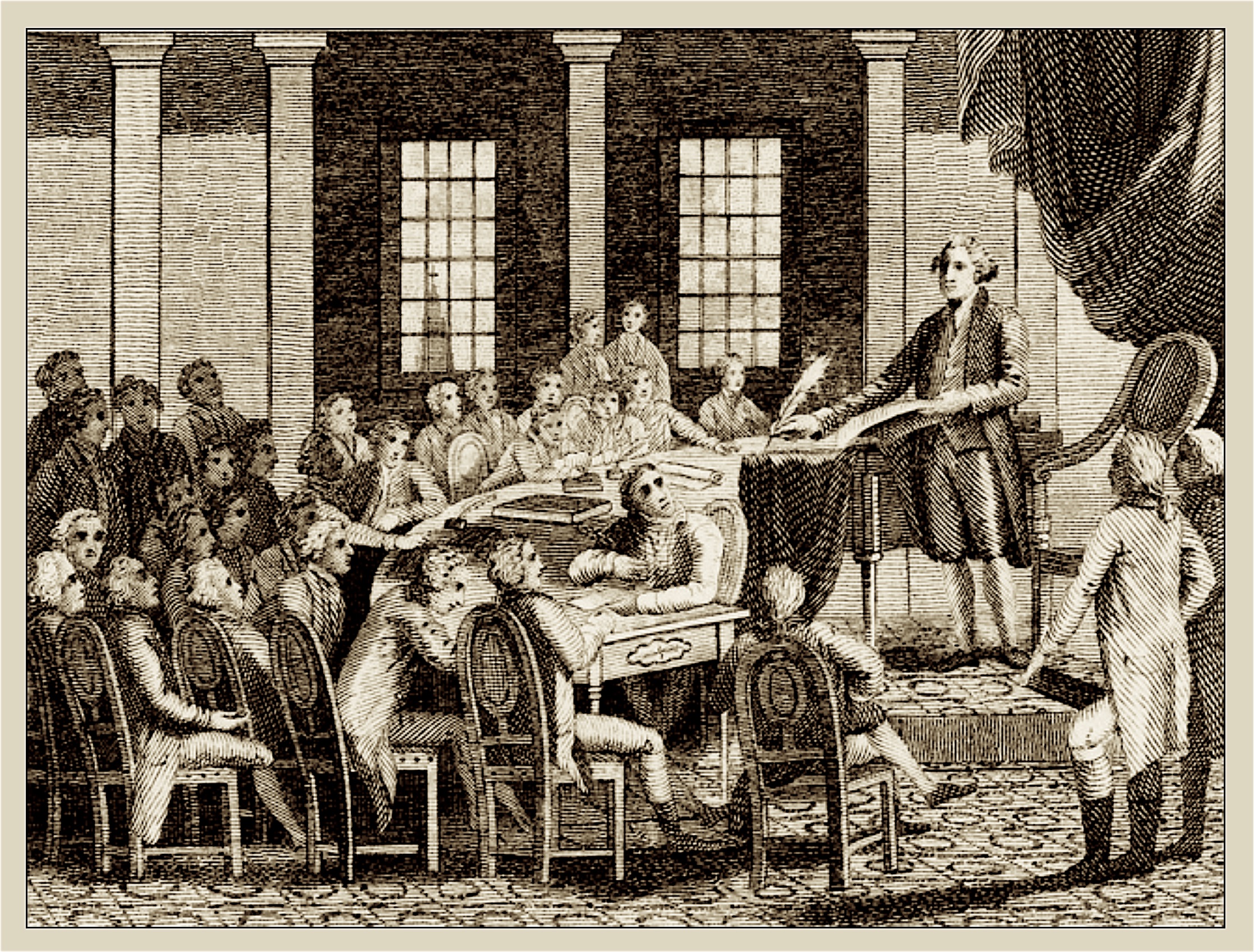

So did James Madison, who spent that summer at the Federal Convention in Philadelphia, shut up through the unforgiving summer heat in the Pennsylvania State House with the windows closed to prevent anyone from eavesdropping. Madison and the other leading delegate, James Wilson of Pennsylvania, were intent on creating a new kind of government — republican in form and spirit, national in scope, and endowed with authority that would enable it to protect the interests of Americans in a world of predatory imperial powers.3

Lesser and less thoughtful men faced with the challenge of governing a continental nation might have done what Jefferson feared and imposed an authoritarian government — a government of wolves over sheep — as lesser and less thoughtful leaders have done before and since. The delegates to the Federal Convention, guided by Madison and Wilson, did precisely the opposite. They built their proposed frame of government on the sovereignty of the people.

At the heart of their plan was a bicameral legislature consisting of a larger lower house and a smaller upper house — later the convention would decide to call them the House of Representatives and the Senate — that would have the power to tax, regulate commerce, impose tariffs, coin money, and make laws governing all matters not delegated to the states. This legislature was to express the sovereign will of the people in making the laws. The Constitution they shaped made no reference to co-equal branches of government or balance of power between separate branches of government. They recognized the need for an independent executive to carry the laws into effect and an independent judiciary to interpret the laws, but the legislature was to be the chief instrument of the sovereign people.

Members of the lower house would be elected by the people in direct proportion to population, each member representing an equal number of citizens. This proposal, which gave substance to the abstract principle of popular sovereignty, was extraordinary. It has since become commonplace, but at the end of the eighteenth century no national legislature had ever been constituted in this way. The British House of Commons, in which members were elected to represent constituencies that varied in size from a few people to thousands and in which many thousands of people went unrepresented, was archaic by comparison.

A government that aims at the public good must begin by finding out the people’s numbers. Hard as it may now be to imagine, eighteenth-century governments did not know with any degree of certainty how many people they governed or where they lived. To the extent they felt any need to know, they relied on estimates and guesswork. To elect a national legislature based on population required counting every American and repeating the process periodically to keep representation in balance with a growing and moving population. The effort to do so reflects the confidence of the Enlightenment in the potential of governments based on rational principles to serve their people rather than subjugate them and the faith of the Enlightenment in the fundamental equality of people.4

Many of the delegates had misgivings about what Madison and Wilson proposed, because many of the problems of the moment seemed to flow from what they regarded as the errors of popularly elected state legislatures. “The people,” Roger Sherman said, “should have as little to do as may be about the government” because “they want information and are constantly liable to be misled.” Vesting the people with sovereign power, skeptical delegates believed, was the problem.5

While acknowledging that democratically elected state legislatures were acting unwisely, Madison and Wilson held the real problem was that no government possessed sufficient authority to address the nation’s ills. They argued that vesting the people with sovereign power was the solution.

Madison credited James Wilson with making the strongest case “for drawing the most numerous branch of the Legislature immediately from the people. He was for raising the federal pyramid to a considerable altitude, and for that reason wished to give it as broad a basis as possible.”

“No government,” Wilson said, “could long subsist without the confidence of the people. In a republican Government this confidence was peculiarly essential.” Confidence would come, Wilson contended, from a legislature that was “the most exact transcript of the whole Society.”6

We look on their work today with the detachment that comes from knowing how the story came out. They managed to draft a constitution that became what is now the world’s oldest continuously functioning written frame of government. We live with its peculiarities and its compromises and imperfections while giving insufficient attention to the magnitude of their achievement and the living ideal on which it is ultimately based — the conviction that the people, though they might not always be well informed, would ultimately choose well.

Madison and Wilson, along with the absent Jefferson, were trained in the moral philosophy of the Scottish Enlightenment. They were convinced by the writings of Francis Hutcheson, David Hume, and other Scottish thinkers that people possess a natural moral sense that guides them and allows them to make judgements quickly and intuitively, without close study or the application of acquired learning.7

In the summer of 1787, Jefferson explained the moral sense in a letter to his nephew Peter Carr, a student at the College of William and Mary, advising him to skip lectures on moral philosophy:

I think it lost time to attend lectures in this branch. He who made us would have been a pitiful bungler if he had made the rules of our moral conduct a matter of science. For one man of science, there are thousands who are not. What would have become of them? Man was destined for society. His morality therefore was to be formed to this object. He was endowed with a sense of right and wrong merely relative to this. This sense is as much a part of his nature as the sense of hearing, seeing, feeling; it is the true foundation of morality . . . The moral sense, or conscience, is as much a part of man as his leg or arm. It is given to all human beings in a stronger or weaker degree, as force of members is given them in a greater or less degree. It may be strengthened by exercise, as may any particular limb of the body. This sense is submitted indeed in some degree to the guidance of reason; but it is a small stock which is required for this: even a less one than what we call Common sense. State a moral case to a ploughman and a professor. The former will decide it as well, and often better than the latter, because he has not been led astray by artificial rules.8

This optimistic view of the capacity of ordinary people to make good moral and ethical judgements is the most important justification of popular sovereignty — the defining ideal of the Federal Constitution — and remains the ultimate foundation of American democracy.

The practical implementation of a theory of popular sovereignty on a national scale was so new that it baffled many of the delegate who gathered in Philadelphia for the Federal Convention. Their anxieties obscured their ability to imagine the future of democratic government. None approached that future with as much confidence as James Wilson, who imagined, he said, “the influence which the Government we are to form will have, not only on our people and their multiplied posterity, but on the whole Globe.” He was, Wilson admitted, “lost in the magnitude of the object.”9

The future of the Constitution still depends on the people, who should remember Jefferson’s admonition that the moral sense needs to be exercised. “Above all things,” Jefferson concluded, “lose no occasion of exercising your dispositions to be grateful, to be generous, to be charitable, to be humane, to be true, just, firm, orderly, courageous etc. Consider every act of this kind as an exercise which will strengthen your moral faculties, and increase your worth.”8

No better advice can be offered to people determined to preserve their freedom.

Notes

- Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, January 30, 1787, Julian P. Boyd, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 11: January 1- August 6, 1787 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1955), 92-97; Thomas Jefferson to William Stephens Smith, November 13, 1787, Boyd, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 12: August 7, 1787 - March 31, 1788 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1955), 355-57. [↩]

- Thomas Jefferson to William Stephens Smith, November 13, 1787, Boyd, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 12: 355-57; Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, January 30, 1787, Julian P. Boyd, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 11: January 1- August 6, 1787 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1955), 92-97. [↩]

- James Wilson did not leave behind a substantial body of correspondence and other papers, so the scholarly literature on him will never be as rich as it is on Madison, Jefferson, and other intellectually sophisticated Revolutionaries. Page Smith, James Wilson, Founding Father, 1742-1798 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1956) is the first scholarly biography. An insightful treatment of Wilson’s thought — perhaps the first whose author did not feel the need to introduce Wilson to readers — is John Fabian Witt, “The Pyramid and the Machine: Founding Visions in the Life of James Wilson” in his Patriots and Cosmopolitans: Hidden Histories of American Law (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007), 15-82. Witt interprets Wilson as an advocate for a unified nation state based on popular sovereignty rather than a pluralist republic of balanced, competing interests. Wilson spoke in the convention 168 times, second only to Gouverneur Morris, who spoke 173 times. Wilson generally spoke at greater length than Morris, and thus was the most active speaker in the convention. [↩]

- On the history of the U.S. census, see Margo J. Anderson, The American Census: A Social History (2nd edition, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015). Efforts to enumerate populations are as old as civilization, but until modern times they were nearly all mandated by monarchs as a tool to extract revenue or military service from their subjects. A systematic census of Iceland commissioned by the king of Denmark conducted in 1702-1703 enumerated 50,358 people with remarkable accuracy and was the first census in the modern sense of the term. [↩]

- Max Farrand, ed., The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787 (3 vols., New Haven: Yale University Press, 1911), 1: 48 (May 31). [↩]

- Farrand, Records of the Federal Convention, 1: 49 (May 31), 1: 132 (June 6). [↩]

- Wilson’s attachment to the moral sense was particularly clear in his later law lectures, in which he said that the “science of morals . . . is founded on truths, that cannot be discovered or proved through reasoning.” See C. Bradley Thompson, America’s Revolutionary Mind: A Moral History of the American Revolution and the Declaration That Defined It (New York: Encounter Books, 2019), 395. [↩]

- Thomas Jefferson to Peter Carr, August 10, 1787, Boyd, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 12: 14-19. [↩] [↩]

- Farrand, Records of the Convention, 1: 405-6 (June 2). [↩]