Portraits are not always what they seem at first sight, especially more than 250 years after they were created. Meaning that was apparent to contemporaries evaporates. Symbolism, once clear, becomes opaque. Visual allusions are forgotten. Consider, for example, Johan Zoffany’s 1771 portrait of George III, which is not as simple as it seems. Zoffany painted it at a tumultuous moment in public life when politics spilled into the streets, which became a stage for riot edging toward rebellion. What now seems like a simple portrait was a political statement expressed in the visual vocabulary of theater, with the king in his greatest role.

Zoffany painted the portrait at a turning point in the long reign of George III. The king had come to throne in 1760 at twenty-two, entirely unprepared for his role. A lazy child difficult to teach, George was eleven before he could read and never learned proper grammar. His father, Prince Frederick, had been heir to the throne but died when George was twelve. As an adolescent George was deeply attached to John Stuart, 3rd earl of Bute, a Scotsman who was a friend of his mother and guided his education, such as it was, and prepared him to succeed his grandfather as king.1

Allan Ramsay’s grand coronation portrait of George III, painted in 1761-62, was a traditional royal portrait. The young king is clothed in ermine and silk and the crown rests on the table at right. Through painted copies and prints this quickly became the most familiar portrait of the king. Royal Collections Trust

Bute and his mother kept the prince away from aristocratic loungers and encouraged his piety, which shaped his ideas about the duty of a king to be a moral exemplar for his people. George believed in Divine Providence and his reign was shaped by a strong sense of moral duty. He was nonetheless congenitally weak-minded, conscious of his own inadequacy, and desperate for familiar support.

George made Bute prime minister shortly after ascending the throne. The king and his favorite were no match for the powerful Whig families who dominated the political life of Britain. Among them were the dukes of Newcastle and Devonshire, William Pitt — a skilled parliamentarian and brilliant speaker who sparred with Newcastle and Devonshire and led Britain to sweeping victories in the Seven Years War — and Pitt’s relatives the ambitious, able, and cunning Grenvilles. George learned to loath them all. Bute was not up to the challenge of managing a government dominated by such men. He resigned and left the insecure young king on his own. That was in 1763 — the year peace was made, Britain’s enemies humbled, and a vast empire secured.

It was a miserable year for George III, who had lost his mentor and felt himself pressed by problems beyond his poor comprehension. For seven years thereafter a succession of prime ministers came and went. Henry Grenville served two years, pressed through a stamp tax on the colonies, and was succeeded by the marquess of Rockingham who oversaw the repeal of the stamp tax during one year in office. He was followed by Pitt, who was elevated to the peerage as the earl of Chatham. Sick and mentally exhausted the whole time, Pitt organized a coalition government Edmund Burke described as “chequered and speckled . . . a very curious show; but utterly unsafe to touch, and unsure to stand on.”2 Pitt’s tenure was dominated by Charles Townshend, chancellor of the exchequer, who secured the passage of duties on paint, paper, lead, tea, and glass imported into the American colonies. Pitt resigned after two years and was followed by the duke of Grafton, who lasted a little more than a year.

The political instability was upsetting to the king. What was worse, none of these ministers had the slightest interest in serving him as a mentor, friend, or even an advisor in more than whatever limited way was required to cultivate the royal favor they needed. Chatham shut himself out of sight and refused to see the king when he offered to come personally to his prime minister.

Bute had impressed upon George the importance of cultivating respect for the monarchy but for the first ten years of his reign the great ministers of state operated with little deference toward him. George was frustrated by the contentious nature of politics. That frustration had little to do with public finance, which he did not understand, or imperial diplomacy, which was beyond his mean comprehension. It flowed mainly from the appearance of disrespect toward his government, which he took personally even if he did not understand what his government was doing or why.

Nathaniel Dance painted this portrait of Lord North in 1773-74. A contemporary of Zoffany, Dance had painted a conventionally regal portrait of George III in 1769. National Portrait Gallery, London

By happenstance the resignation of Grafton led to the elevation of a new prime minister much more to the king’s liking. Frederick North, who had become chancellor of the exchequer upon the sudden death of Townshend, succeeded Grafton in early 1770.

North was a heavy, indolent man who bore a striking physical resemblance to the king, with the same flabby features and bulging eyes. A rumor circulated that the king’s father, Prince Frederick, was North’s father, but the evidence is slight and circumstantial. The prince had a reputation for taking liberties with other men’s wives. North’s father was lord of the bedchamber to Prince Frederick, who stood as the child’s godfather. The rumor may have been gossip, though the king’s eldest son — later King George IV — said many years later that he thought it was true.3

Although North resembled the king he was much smarter. He was a capable administrator and a witty, charming debater in the House of Commons. The king was drawn to him because North had a deep reverence for the monarchy and treated him with the deference for which he longed. They had other things in common. Like the king, North preferred settled family life to the rakish indulgences common among aristocrats. North was also a serious man who conferred with the king and made the monarch feel he was fulfilling his destined role.

A united opposition led by Chatham, Rockingham, and Grenville resisted North’s leadership for several months, but North outmaneuvered them. His ministry negotiated a swift and successful conclusion to a naval confrontation with Spain over the remote Falkland Islands, dashing Chatham’s hope of returning to lead a war ministry. The uneasy opposition alliance disintegrated thereafter as moderates and wait-and-see members shifted their support to North. By early 1771 his ministry had a secure majority in the Commons, much to the king’s relief. “The seeing that the Majority constantly increases,” the king wrote to his new prime minister, “gives me great pleasure.”4

II

The artist who painted the king’s portrait at that auspicious moment, Johan Zoffany, had arrived in Britain in 1760, the year George ascended the throne. Zoffany was then twenty-seven. Despite his youth he had already spent several years painting in Italy and his native Germany, where he had been, most recently, a “court and cabinet painter” to the Prince-Archbishop of Trier. Zoffany spoke little English at first and briefly made his living painting decorations on clocks, but he was talented, personable, and energetic and soon found better work painting drapery and backgrounds for Benjamin Wilson, a portrait painter whose studio was in fashionable Bloomsbury. The work was beneath Zoffany’s talent but gave him an opportunity to meet potential patrons of his own, including David Garrick, the flamboyant actor-director who dominated the London stage. Garrick commissioned Zoffany to paint him performing a scene from a theatrical interlude he had written and published as a tribute to his friend William Hogarth, the first important English artist to portray actors on stage.5

Garrick’s commissioned Zoffany to paint the comic moment in The Farmer’s Return when the farmer tells his family he encountered a London ghost famed for answering questions by knocking — once for yes and two for no — and that it knocked twice when he asked whether his wife had been faithful to him. But, he added, the ghost was “was much giv’n to Loying.” Johan Zoffany, David Garrick and Mary Bradshaw in David Garrick’s ‘The Farmer’s Return,’ ca. 1762. Paul Mellon Collection, Yale Center for British Art

The painting was a great success and Zoffany quickly established himself as a painter of theatrical subjects. He had a gift for capturing the most memorable moments in the most popular plays, particularly the comedies in which Garrick excelled. Humor in those plays involved word play that was probably opaque to Zoffany, who needed time to develop a command of English, but this may have been a benefit to him. He focused on the gestures, postures, and facial expressions that made these moments memorable to their audiences. “The painter absolutely transports in imagination back again to the theatre,” a newspaper critic wrote, not taking note of the fact that Zoffany depicted the characters in furnished rooms rather than in front of scenery flats and lit them in natural ways that would have been impossible in an eighteenth-century theater.6 Zoffany’s theatrical paintings succeeded because they were idealized — depicting what audiences remembered and imagined, not exactly what they had seen.

Zoffany was inspired by Hogarth’s work, which included paintings based on situations in plays Hogarth exploited to comment on virtue and vice.7 Zoffany also mastered conversation pieces — a kind of group portrait Hogarth had popularized, depicting family or friends socializing in informal settings. Hogarth was sixty-three in 1760 — too old to take on a protégé — but Zoffany missed no opportunity to socialize with him. Zoffany attended the St. Martin’s Lane Academy, which Hogarth had established, and made a careful study of Hogarth’s work. He collected many of Hogarth’s etchings and engravings, rich in visual allusions and symbols.8 Like Hogarth, he befriended printers who published engraved versions of his works. And in 1764, having started to earn a comfortable income, Zoffany rented a country house on the Thames very close to Hogarth’s rural retreat in Chiswick.9

Zoffany’s theatrical paintings, many of them commissioned by David Garrick, established his reputation in the mid-1760s. Above is Parsons, Bransby, and Watkyns in a Scene from ‘Lethe,’ painted in 1766, depicting a scene from Garrick’s first play, a burlesque upon characters of Henry Fielding. Birmingham Museum Trust/Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery. Below is David Garrick as Sir John Brute in Vanbrugh’s ‘The Provok’d Wife,’ painted between 1763 and 1765, It portrays Garrick as Sir John Brute — one of his favorite roles — disguised in a woman’s clothes and being accosted by night watchmen while on drunken spree with his friends. Claiming to be “Boudoucca, Queen of the Welchmen” he threatens to destroy their legions with “a leek as long as my pedigree.” Wolverhampton Art Gallery

In 1763 Lord Bute, whose country house at Kew was near Chiswick, commissioned Zoffany to paint group portraits of his children. Shortly thereafter Bute seems to have introduced the artist to the king and queen — or just as likely, the countess of Bute, who was a friend of the queen, introduced the artist to them. Given their interest in the theater, the royal couple may have already seen and admired Zoffany’s theatrical paintings. However it happened, the king commissioned Zoffany to paint a group portrait of his two sons, George, prince of Wales, and his brother Frederick, later duke of York.10

Zoffany completed these paintings by late 1764. By then Hogarth had died, leaving Zoffany the leading painter of conversation pieces and theatrical scenes in London. He was also a favorite at court — especially of the queen, originally Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, with whom he spoke in their native German. The king appointed Zoffany to the new Royal Academy in 1769 and the next year commissioned the artist to paint a group portrait of the royal family — himself, the queen, and their six children. With the king’s approval Zoffany exhibited the painting at the Royal Academy. Zoffany’s friend Robert Sayer published a fine mezzotint of the group portrait, which brought Zoffany’s work to a wider audience and earned him a tidy income.

Johan Zoffany, George III, Queen Charlotte, and the Six Eldest Children, 1770. Royal Collections Trust. Their most Sacred Majesties George IIId and Queen Charlotte with his Royal Highness George Prince of Wales, Frederick Bishop of Osnaburg, Prince William Henry, Princess Charlotte August Mattilda, Prince Edward, and Princess Sophia, mezzotint by Richard Earlom after Zoffany, London, Robert Sayer, 1771.

The success of the family portrait led to the most coveted commission of all — a commission to paint a new portrait of the king. The most familiar portrait of George III was then the lavish coronation portrait painted by Allan Ramsay in 1761-62 — a life-sized standing portrait of the king in a profusion of silk and ermine. Ramsay’s studio produced dozens of replicas of the portrait that were supplied to colonial governments and British ambassadors on the European Continent. Together with thousands of engraved copies they made it the best known portrait of George III.

Zoffany imagined something completely different — a portrait of the king in a relaxed domestic manner, leading the aristocracy and the gentlemen of his realm as well as his ordinary subjects — a unifying monarch, above partisanship, confident and comfortable in his role.

III

The king was neither confident nor comfortable in 1771. He was grateful to North for insulating him from the byzantine maneuvers of aristocratic factions, but he was perplexed and disturbed by politicians who stirred up opposition to his government among ordinary people. Despite his determination to promote the best interests of all his subjects, the king had no clear conception of how to deal with the changing and increasingly fractious — and even rebellious — nature of popular politics and its leaders.

Fueled by an increasing volume of pamphlets, leaflets, broadsides, and inexpensive news sheets, often scurrilous and filled with invective, the political world of the coffee houses and the streets was remote from the aristocrats and the country gentlemen upon whom the king relied and through whom he sought to maintain harmony in his realm. Its leaders, whether in London or Boston, had little regard for honors bestowed at court. They operated outside the traditional structure of political power, in which order was maintained by distributing offices, sinecures, pensions, and other favors through networks associated with aristocrats.

In 1771 the most prominent leader of this sort was John Wilkes, who was as bizarre a character as eighteenth-century politics produced.11 The son of a distiller, educated at the University of Leyden, Wilkes was cross-eyed and by most accounts unusually ugly. But this did not limit his rise in society, discourage his taste for lewdness, nor diminish his claims of prowess with women. He said that with ten minutes head start to work his charms he could outmaneuver the handsomest man in Britain.12 For men willing to overlook his vices Wilkes was good company. “I scarcely ever met with a better companion,” Edward Gibbon wrote, “he has inexhaustible spirits, infinite wit and humour, and a great deal of knowledge.” Wilkes enjoyed the company of artists and actors and was friends with David Garrick and his circle.13

Elected to Parliament for Aylesbury in 1757, he told a group of drunken companions, including the usually reserved Gibbon, that he was determined to take advantage of “public dissension . . . to make his fortune.” His aim was some ministerial sinecure or an ambassadorship, and he made enough friends in Whig circles to make this aim plausible.14

This aim was derailed by the rise of Bute, who recognized Wilkes as a vulgar adventurer and made no secret of it. When George III installed Bute as prime minister in 1762, Wilkes launched a weekly news sheet, The North Briton, to undermine his ministry. Thus far Wilkes was much like any other opposition politician of the eighteenth century: denied favors reserved by the ruling ministry for its friends, he set out to embarrass it, hoping to dislodge it or force it to buy his support. What distinguished Wilkes was his methods, his skill as a writer, the risks he was willing to take, and his precocious skill at attracting and mobilizing the enthusiastic support of ordinary English men and women.

Wilkes attacked Bute’s character — insinuating that Bute was having an affair with the king’s mother, for which there wasn’t the slightest evidence — and Bute’s efforts to end the Seven Years’ War on terms Wilkes said conceded too much to France. Facts were of little importance to Wilkes. “Give me a grain of truth,” he boasted privately, “and I will mix it up with a great mass of falsehood so that no chemist will ever be able to separate them.”15 He gored most of the king’s ministers — Lord Egremont, he wrote, was “a weak, passionate, and insolent secretary of state” and Secretary to the Treasury Samuel Martin “the most treacherous, base, selfish, mean, abject, low-lived and dirty fellow, that ever wriggled himself into a secretaryship.”16 His arguments were popular with the London crowd, which gloried in the humiliation of France, distrusted a Scotsman as prime minister, and had no grasp of the fiscal pressures with which Bute had to deal. Wilkes sustained his vendetta against Bute until the prime minister resigned in April 1763.

Not satisfied with Bute’s resignation, Wilkes turned his attack on Bute’s successor. But he went too far in criticizing the king’s speech to Parliament at the end of April. In North Briton Number 45 Wilkes called the speech “the most abandoned instance of ministerial effrontery ever attempted to be imposed on mankind.”17

He was arrested for seditious libel and jailed in the Tower. Posing as a victim of an arbitrary political prosecution and a champion of free speech, Wilkes announced in court that his trial would “determine at once whether English liberty be a reality or a shadow,” especially for “all the middling and inferior set of people, who stand most in need of protection.” He secured his release by casting doubt on the legitimacy of the arrest warrant and claiming that as a member of Parliament he was exempt from such prosecution. The crowd delighted in his success.18

John Wilkes Esqr. Drawn from the Life and Etch’d in Aquafortis by Willm Hogarth, May 16, 1763. John Wilkes, who decorated his parlor with Hogarth prints, owned this copy. Eighteenth-century print collector George Steevens purchased it at the sale Wilkes’ library. It is now in the George Steevens’s Collection of Hogarth Prints in The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.19

The Bruiser, C. Churchill (once the Revd) in the Character of a Russian Hercules, Regaling Himself after having Kill’d the Monster Caricatura that so Sorely Gall’d his Virtuous friend, the Heaven born Wilkes, William Hogarth, August 1, 1763, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Wilkes and his friends responded in kind. Charles Churchill, a poet and contributor to The North Briton, wrote An Epistle to William Hogarth, savaging the artist in verse for surrendering to vanity, envy, and malice. Hogarth retaliated with a satirical portrait of Churchill as a drunken bear in torn clerical garb (Despite having been an Anglican priest he was known as a brawler). Hogarth’s alter ego — his dog Trump — urinates on Churchill’s Epistle in the foreground. Wilkes’ supporters responded with prints ridiculing Hogarth as a corrupt agent of the ministry with a bag of government money tied to his arm and a cloven hoof stepping on a liberty cap; as an ass wearing a boot (a pun on Bute) with The Bruiser on his easel, while Wilkes fits him with a cuckold’s horns; as an aging, impotent tool of the ministry with the caricature of Wilkes on his easel; and one depicting Wilkes strangling Trump in a noose while Churchill flogs him without mercy.20

An Answer to the Print of John Wilkes Esqr by Wm Hogarth ([London], n.p., 1763), The Bruiser Triumphant. A Farce (London: E Sumpter, 1763), both from the George Steevens’s Collection of Hogarth Prints, The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University, and Tit for Tat or Wm Hogarth Esqr Principal Pannel Painter to his Majesty (London: J. Pridden, 1763), British Museum

Pug the snarling Cur chastised, or a Cure for the Mange. prepared by J. Wilkes Esqr and C. Churchil (London: sold by E. Sumpter, [1763]). British Museum

Although Hogarth’s caricature was intended to hold Wilkes up to ridicule, the image was taken up by Wilkes’ supporters as a symbol of their idol. Thousands of copies were sold. The print was displayed in windows and tacked up in taverns. It even appeared on punch bowls and other commemorative items celebrating the popular politician who was standing up to the king’s ministers in defense of civil liberties. The image could be found, in its various forms, all over England, and it soon reached Britain’s American colonies. Nor did it fade from popular memory. In February 1770 a man appeared at masquerade dressed as Wilkes, with a cross-eyed mask and carrying a pole topped with a liberty cap, just as in Hogarth’s caricature.22

Punch bowl commemorating John Wilkes, Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1764–70, Winterthur Museum, Garden, & Library, Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont, 1960

When Parliament reconvened in the fall the House of Lords charged Wilkes with obscenity and blasphemy for publishing a lewd poem, an offense not covered by parliamentary immunity. Rather than face prosecution he fled to France. He was then declared an outlaw and promptly expelled from the House of Commons.

Wilkes returned to Britain in 1768 and stood for election to the House of Commons from Middlesex (the county bordering London on the north and west), employing his formidable skills to work the London crowds into a frenzy. “London was illuminated two nights running at the command of the mob for the success of Wilkes in the Middlesex election,” Benjamin Franklin wrote, adding

the second night exceeded any thing of the kind ever seen here on the greatest occasions of rejoicing, as even the small cross streets, lanes, courts, and other out-of-the-way places were all in a blaze with lights, and the principal streets all night long, as the mobs went round again after two o’clock, and obliged people who had extinguished their candles to light them again.23

After securing his election Wilkes surrendered to the authorities to face trial. As soon as he was jailed a crowd of as many as 15,000 demonstrated outside the prison. In the resulting confrontation between the crowd and troops sent to maintain order at least six protestors and bystanders were killed. Dubbed the “St. George’s Field Massacre,” the incident galvanized popular support for Wilkes. He was nonetheless convicted and spent twenty-two months in prison, during which he was expelled from the House of Commons. Claiming that a corrupt ministry was interfering with the right of freeholders to the representative of their choice, Wilkes was re-elected three successive times between February and April 1769. Parliament declared each election void and finally seated his opponent.

Prosecution, expulsion, and imprisonment made Wilkes more and more the darling of the crowd. The Middlesex elections were a partisan circus. “Wilkes and Liberty” was the popular cry. His supporters chalked “45” on doors, shutters, walls and bridges, and even on the sides of passing carriages.24 They pinned it on their hats. It was the mob’s password. Layered with meanings, it served many purposes. It was at once an allusion to the offending issue of the North Briton, which few in the crowd had read, and to “the 45,” the Scots rebellion of 1745, which had aimed at placing the Stuart pretender on the throne. Wilkes used the number as a jab at Bute (a distant kinsman of the Stuart monarchs), claiming that Bute continued to mislead the king.

Elaborate festivities marked Wilkes’ release from prison in April 1770. Newgate prisoners illuminated their windows. So did Londoners on the principal streets. The poor burned lights along the back alleys, lanes, and courts in honor of their hero. In Greenwich musicians played in the streets, houses and shops were illuminated, and the Greyhound Inn was lit up with some three hundred candles forming the words “Wilkes and Liberty.” Crowds gathered in the market square for a fireworks display in which rockets were fired every forty-five seconds for an hour and forty-five guns were discharged. Similarly theatrical celebrations were staged in towns across the south of England from Kent to Cornwall.25

Wilkes flooded London with handbills promoting his cause. Often they were adorned with a portrait or included tributes to “Wilkes and Liberty” in verse and were sold for a penny or passed from hand to hand for free. In this contemporary print of a scene outside a debtor’s prison, a woman peddles handbills while a boy chalks “45” on the back of a lawyer buying one of the cheap prints. British Museum

To Wilkes politics was theater. “He was an incomparable comedian in all he said or did,” wrote Nathaniel Wraxhall, who knew Wilkes, “and he seemed to consider human life as a mere comedy.” His ability to keep the crowd entertained was the foundation of his appeal.26

Many observers found the passion for Wilkes inexplicable. He was a poor public speaker. His bizarre appearance, vulgar antics, lewdness, habitual turning on those who had been his friends, and thinly veiled expressions of contempt for ordinary people — none of these things diminished his support. What those observers did not understand was that Wilkes was the darling of Britons who were frustrated by the status quo and imagined themselves victims, not of economic or demographic forces they did not comprehend but of a ministerial conspiracy to manipulate law and public policy for the benefit of an entrenched governing class they deeply distrusted. It was not the real John Wilkes they adored. It was their idea of John Wilkes that mattered. He was a champion who would save them or a martyr whose sacrifice would expose their oppressors — it was never clear which they imagined. Probably both at once. And that idea of John Wilkes could endure criminal prosecutions, accusations of impropriety, and his very real indiscretions.

The extent to which the public life of London was consumed by Wilkes between 1768 and 1771 can scarcely be overestimated. His admirers invested him with the symbolic importance normally attached to the king. They pasted handbills on church walls urging the clergy to pray for “Wilkes and Liberty.” To his followers his name was synonymous with English liberty, so when they cried out “No Wilkes — No King” they meant “No Liberty — No King.” And in their enthusiasm they raised their loyal toasts to Wilkes instead of George III.27

V

George III loathed Wilkes. Thomas Whately reported that the king “sat up all the first night of the illuminations, the Monday night, full of indignation at the insult, and saying to those about him, who expressed apprehension of the mob coming to the Queen’s house, that he wished they would push their insolence so far; he should then be justified in repelling it, and giving proper orders to the Guards.” The king insisted on Wilkes’ expulsion from the Commons and rejected the suggestion that he might bury the controversy by pardoning him and then ignoring his antics.28

This engraving of the riot outside St. James’s Palace was published in the London Magazine in April 1769, shortly after the event. Protesters have smashed the windows of the carriage at upper right. At lower right a gentlemen pulled from his carriage is being roughed up by the crowd. At left is a hearse decorated with a placards and paintings of two people killed in Brentford during the Middlesex elections and those who died in St. George’s Fields in 1768. It followed the merchant’s procession to the palace. British Museum29

The king demonstrated remarkable forbearance when a mob gathered outside St. James’s Palace on March 22, 1769 — at the height of he election controversy — while he was inside waiting to receive a delegation of London merchants. The mob stopped the merchant’s procession at the Temple Bar, then harassed them as they made their way to the palace, stoned and overturned carriages, and pelted the merchants with dirt and trash. Thousands gathered outside the palace. Some of them sang “God save Great Wilkes our King.” Troops stationed there beat to arms. the mob pressed forward, “up to the muzzles of their firelocks,” the duke of Chandos wrote, but they held their fire. A dozen merchants, their clothes dirty and torn, finally made their way inside the palace to present their address to the king. “He carried himself so,” wrote Lord Holland, “that it was hard to know whether he was concerned or not. A lord who is near him told me that after the great riot at St. James’s, or rather in the midst of it, you could not find out, either in his countenance or his conversation, that everything was not quiet as usual.” He was “quite calm and serene,” Thomas Whately thought, “and expressed his hopes that this event would be the means of gaining effectual support to Government from all who wished well to their country.”30

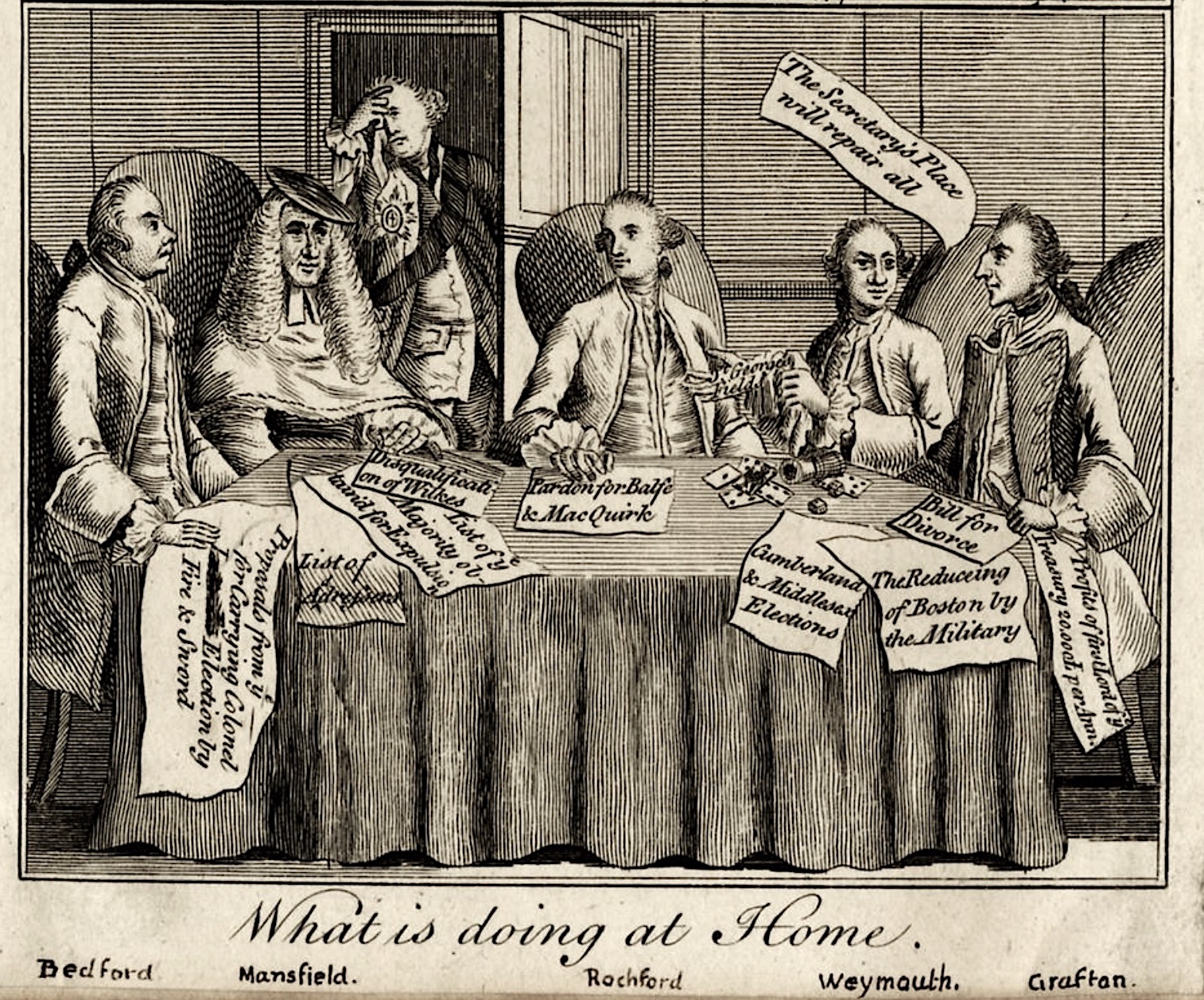

In 1769 the ministry’s obsession with Wilkes excited criticism and ridicule. In this cartoon from the Political Register, King George listens while his minister discuss public affairs. Grafton, the prime minister, at right, is concerned with his divorce, lining his pockets, and suppressing popular unrest in Boston through military occupation. To his right, Weymouth, secretary of state for the northern department (and reputedly a degenerate gambler and womanizer) is focused on the use of force to suppress protests in favor of Wilkes. The blood spilled in the St. George’s Field Massacre of 1768 is still on his hands. At center, Rochford wants to secure pardons for Balfe and McQuirk, two Irish bruisers convicted of killing Wilkes supporters in an election brawl. Lord Mansfield is preoccupied with the disqualification of Wilkes, and Bedford, at left, is determined to secure the election of Wilkes’ opponent, Colonel Henry Luttrell, “by Fire and Sword” if necessary. British Museum

Londoners booed the king as he passed in the royal carriage on his way give his assent to acts of Parliament. He did his best to ignore the affront, even when one of his subjects hit the carriage with a rotten apple. By the spring of 1771 the king counseled Lord North that treating Wilkes carefully — giving him no new occasion to stir up the London crowd — was the prudent course and would hasten the end of what he called “this unpleasant affair.” The king’s wishes were soon widely known. “The Ministers avow Wilkes too dangerous to meddle with,” a member of the Commons told Chatham. “He is to do what he pleases; we are to submit. So His Majesty orders: he will have nothing more to do with that devil Wilkes.”31

This required a considerable degree of discipline. In the king’s eyes Wilkes was lewd, licentious, dissolute, dishonest, and disloyal. He was blasphemous, coarse, and vulgar. He was factious, thrived on discord, and constantly misled the king’s subjects. George III saw himself as everything Wilkes was not: pious and moral, a loyal husband and dedicated father. He hated partisanship and longed to be respected as the common father of all his people at the head of a unified nation.

Johan Zoffany had little in common with the king. He was neither pious nor particularly moral. He was occasionally blasphemous, licentious, and lewd. His young wife, miserable in London, had long since moved back to Germany. Thereafter Zoffany had posed as a widower and had a series of mistresses before taking up with the teenage daughter of a London glovemaker, whom he ultimately married. Among his several self-portraits is one in which he is donning a monk’s habit; in the background are liquor, playing cards, a print of a female nude, and two condoms. A sociable man, Zoffany spent much of his time in coffee houses and taverns and the homes and studios of friends and fellow artists. He was vain, contentious, and opinionated, indulged a taste for flamboyant clothes, spent freely, and occasionally drank too much. “He was a very ugly man,” an acquaintance wrote, “tall, and very much marked with the small pox.” Zoffany also suffered from misalignment of the eyes. He had much more in common with the risqué John Wilkes than with George III, though the king was probably not aware of Zoffany’s vices when he posed for his portrait.32

Johan Zoffany, Self-Portrait, ca. 1775. Galleria degli Uffizi

Never before had a British monarch been presented in such a casual way. Zoffany portrayed the king as a self-confident, untroubled man. He looks relaxed but resolute. His right arm rests on the arm of his chair. His left hand rests on his thigh, pointed in the direction he is looking, out of the frame to the viewer’s right. The setting, with its elaborate gilded table and finely upholstered chair, is elegant, but not regal. A bicorn hat and sword take the place of the crown and scepter usually depicted in royal portraits.

Despite the portrait’s air of elegant informality, no contemporary viewer could have confused the sitter with a country squire. He wears a general’s coat and the sash and star of the Order of the Garter, England’s highest order of chivalry, in which membership was limited to the sovereign and twenty-four companions chosen by the king. The embroidered garter below his left knee is part of the order’s insignia. Membership in the order was the highest of the many honors at the king’s disposal.

By emphasizing the king’s role as head of the order, Zoffany alluded to the very traditional idea of the king unifying the realm by drawing the extended royal family and the landed aristocracy together under his leadership through the distribution of honors. The casual air of his pose signals his intention to lead the country gentlemen who were having their own portraits painted in the same relaxed style.

Johan Zoffany, George III, 1771. Royal Collections Trust

Zoffany claimed for the king the popular role occupied by John Wilkes by appropriating the very pose — seated, legs splayed, left hand resting on the subject’s left thigh, and face turned to the viewer’s right — Hogarth had used in his famous caricature of Wilkes. In place of Wilkes’ pen and inflammatory newspapers, Zoffany placed the king’s hat and sword, which the self-assured king, in his military attire, was prepared to take up in defense of his realm. The highlighted edge of the gold ribbon on the king’s hat suggests Hogarth’s serpentine “line of beauty,” which for Hogarth conveyed grace, energy, and liveliness.33 Zoffany included no extraneous details — no carpet, columns, or draperies, no window or open door. The portrait is a theatrical painting, with the central figure bathed in light on an otherwise darkened stage. The broad expanse of dark above the king invites recollection of the staff and liberty cap held by Wilkes. The motto on the king’s garter — “Honi soit qui mal y pense,” meaning “Shame on him who thinks ill of it” — admonishes Wilkes, who had dared to libel his monarch. With this daring visual allusion Zoffany presented George III as he wanted to be known: as a patriot king, above the partisanship that was dividing his subjects and threatening his kingdom and his empire. And without mentioning his name, Zoffany cast Wilkes as a lord of misrule, a jester.34

The king was undoubtedly in on Zoffany’s joke. With his approval Zoffany entered the painting in the third annual exhibition of the Royal Society, where thousands saw it. Robert Laurie and Richard Houston, two of England’s finest mezzotint artists, each copied the portrait on copper plates from which thousands of impressions were made and sold. Other artists copied Zoffany’s work, most memorably Quaker needleworker Mary Knowles, a master of the eighteenth-century art of ‘needlepainting.’ She stitched a full size embroidered copy of Zoffany’s portrait of the king. Knowles was so touched by the queen’s appreciation of her work — the queen made her a gift of eight hundred pounds — that she stitched a portrait of herself working on the project. The king and queen had her embroidered copy of Zoffany’s portrait hung in the royal palace at Kew, were it remained on view for two hundred years. It reflected the kind of respect the king wished for from his subjects.35

Mary Knowles, needlework self-portrait, 1779. Royal Collections Trust

George III could not have known that within a few years his ambition to rule an empire free of discord and faction, his people unified in appreciation of his benevolence, would be dashed, and that he would make war on his own subjects. Nor could Zoffany have known that he had reached the peak of his career in Britain. In 1772 he accepted a commission from the queen to paint a detailed view of the Tribuna, an octagonal room in the Uffizi Palace where great works from the Medici art collection were displayed. He spent the next seven years abroad, mostly in Florence.

He returned to London in the fall of 1779 to find circumstances much changed. Britain was at war with its former American colonies and with France. Garrick had just died and the once lively market for theatrical paintings had slowed. The patrons who had kept Zoffany busy had new favorites. Thomas Gainsborough had moved from Bath to London and was in constant demand. George Romney had taken over a large share of the remaining portrait business. The king and queen did not care for Zoffany’s painting of the Tribuna — apparently unhappy about the number of English travelers and expatriates the artist included in the painting and with the long years it had taken to fulfill the commission. Zoffany had to rebuild his business without royal patronage.36

Johan Zoffany, John Wilkes and his daughter Polly, 1782. Purchased with help from the National Heritage Memorial Fund and the Art Fund, 1991, National Portrait Gallery, London

His first important commission came from none other than John Wilkes. In Zoffany’s absence Wilkes had been elected to Parliament from Middlesex and taken his seat without objection. In 1779 he was elected chamberlain of London, a position of financial trust he occupied for the rest of his life, fulfilling his ambition to secure a stable and honorable position in public affairs. He had put political radicalism behind him. Wilkes commissioned Zoffany to paint a double portrait of himself and his daughter, Polly.

For all of his rakish vices, Wilkes was a devoted father — an aspect of his character Zoffany emphasized by avoiding any visual allusion to Hogarth’s famous caricature. Wilkes looks fondly at Polly. The dog at his feet is a symbol of fidelity. If we didn’t know better, we would mistake Wilkes for a simple country squire. Horace Walpole, who disliked Wilkes, described it as “a delightful piece of Wilkes looking — no, squinting tenderly at his daughter. It is a caricature of the Devil acknowledging Miss Sin in Milton.”37 In fact the portrait was a reflection of Wilkes’ vision of himself, just as Zoffany’s portrait of King George III was a reflection of the king’s aspiration to be respected and admired by all of his subjects. Zoffany had a gift for portraying his subjects — kings and commoners, actors and aristocrats — as they imagined themselves, each an actor in a favorite role.

Notes

- In his recent biography, Andrew Roberts, The Last King of America: The Misunderstood Reign of George III (New York: Viking, 2021), the author successfully dismantles a straw man — the idea that George III was a heartless tyrant without redeeming qualities — that hasn’t been fashionable since the nineteenth century. He doesn’t succeed in dispelling the more recent view that the king loved his wife and children and wanted to be a good ruler but was too weak minded to be an effective monarch. Andrews’ account is akin to a nineteenth-century life and times biography in which the king plays at most a minor role in the great events of his reign. [↩]

- The Works of the Right Honorable Edmund Burke, vol. 1 (London: George Bell & Sons, 1889), 425. [↩]

- Dick Leonard, Eighteenth-Century British Premiers — Walpole to the Younger Pitt (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 167; George IV’s quip that either his royal grandmother or North’s mother had “played her husband false” is recorded in W. H. Wilkins, Mrs. Fitzherbert and George IV (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1905), 110. The rumor had been around for decades. Charles Townshend was probably alluding to it in the 1760s when he described North as “that great, heavy, booby-looking, seeming changeling” (W. Bodham Dunne, ed., The Correspondence of King George III with Lord North from 1768 to 1783 (2 vol., London: John Murray, 1867), 1: lxxxi). [↩]

- The establishment of a stable ministry is ably summarized in John B. Owen, The Eighteenth Century, 1714-1815 (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1974), 197-205; George III to Lord North, February 28, 1770, Royal Archives [GEO/MAIN/948]. This note is published in John Fortescue, ed., The Correspondence of King George III from 1760 December 1783, vol. 2 (London: MacMillan and Co., 1927), 132. [↩]

- Zoffany has not attracted the attention lavished on his famous contemporaries, including Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough. Unlike them he was a foreigner who came to Britain as an adult at a time when British painting was dominated by a remarkable generation of native artists proud to distinguish themselves from their Continental peers. He left behind little correspondence or other papers — notebooks, sketches and so on — that might be used to reconstruct his story. His personal papers and sketches were deliberately burned with the household goods of his second wife after she died in the terrible cholera epidemic in London in 1832. The cause of cholera was not yet understood and the personal effects of victims were burned in a vain effort to stop the spread of the disease. What we have are his paintings and just enough documentation to appreciate, if not fully understand, his relationships, influences, and aims. The first biography of any scope or consequence was Victoria Manners and G. C. Williamson, John Zoffany, R.A.: His Life and Works (London: John Lane, 1920), a pioneering effort, suggestive here and there but riddled with errors. Mary Webster, Johan Zoffany, 1733-1810 (London: National Portrait Gallery, 1976), an exhibition catalogue, is based on sound research, though it takes no notice of the 1771 portrait of George III. The most authoritative treatment of Zoffany and his work is Penelope Treadwell, Johan Zoffany: Artist and Adventurer (London: Paul Holberton, 2009), [hereafter Treadwell, Zoffany] a superb biography with hundreds of color illustrations of paintings by Zoffany and others. The book is filled with useful insights and engaging interpretations of Zoffany’s work making the most of fugitive documentary evidence, the artistic context in which Zoffany’s worked, and the paintings themselves. The lack of written documentation makes a strictly chronological treatment impractical. Treadwell departs from strict chronology to treat some of Zofanny’s work in thematic chapters corresponding to the phases of his career. She addresses his royal commissions in “‘Conversations’ at the Royal Court,” pp. 97-121. She deals with Zoffany’s 1771 portrait rather quickly, contending that the king’s informal pose was intended to emphasis the king’s “humanity” and relates it to the king’s interest in agriculture (pp. 115-18). Martin Postle, ed., Johan Zoffany RA: Society Observed (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011) [hereafter Postle, ed., Society Observed] is a scholarly companion to a very fine exhibition of the same name displayed at the Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, and the Royal Academy of the Arts, London, in 2011-12. It includes essays by several authors as well as a catalogue of the exhibition. [↩]

- quoted in Treadwell, Zoffany, 61. [↩]

- See, for example, Hogarth’s The Lady’s Last Stake, painted around 1759, which depicts a scene in a play of the same name in which a wealthy married woman, having gambled away her fortune to a handsome army officer, considers his offer to return it all if she will risk her virtue on a final wager. This painting was displayed at the Society of Artists exhibition in 1761. Zoffany undoubtedly saw it there. The painting does not depict a performance of the play and is set in the drawing room of a well-appointed Palladian house. The painting is now in the Buffalo AKG Art Museum. [↩]

- “Other pictures we look at,” Charles Lamb wrote, “but his prints we read.” Charles Lamb, “On the Genius and Character of Hogarth,” The Reflector, vol. 2, no. 3 (1811), 61-77. [↩]

- On Zoffany’s friendship with Robert Sayer, one of London’s most important print publishers, see Postle, ed., Society Observed, 25; on Zoffany’s rural retreat near Hogarth, see Treadwell, Zoffany, 95. Hogarth died suddenly a few months after Zoffany rented the house in Chiswick. [↩]

- On the portraits if the Bute children, see Postle, ed., Society Observed, 244-45; Webster, Johan Zoffany, 1733-1810, contends (p. 30) that Bute probably introduced Zoffany to the king after the completion of these works, but searched for documentary evidence of this without success. Pamela Treadwell notes that the royal family was living at Richmond Lodge, near the Bute’s residence at Kew, when the paintings of the Bute children were completed; Treadwell, Zoffany, 106-7. [↩]

- There is a large literature on Wilkes. The standard modern biography is Arthur H. Cash, John Wilkes: The Scandalous Father of Civil Liberty (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006); on Wilkes’ supporters, see George Rudé, Wilkes and Liberty: A Social Study of 1763 to 1774 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1962); on the place of Wilkes in the political dynamics of the 1760s and early 1770s, see John Brewer, Party Ideology and Popular Politics at the Accession of George III (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976), 163-200. [↩]

- [Frederick Reynolds], The Life and Times of Frederick Reynolds. Written by Himself (2 vols., Philadelphia: M. C. Cary and I. Lea, 1826), 26, reports that Wilkes told the author “in affairs of gallantry, my victories are not ten minutes behind those of the handsomest men in England.” The claim is reported as thirty minutes is some secondary works, without citation. Wilkes may have made the boast both ways. [↩]

- Edward Gibbon, Miscellaneous works of Edward Gibbon, Esquire. With Memoirs of his Life and Writings, Composed by Himself (2 vols., London: A. Strahan, and T. Cadell Jun. and W. Davies, 1796), 1: 100 [Journal entry for September 23, 1762]; Gibbons’ judgment was echoed by many others. James Boswell found described Wilkes as “a most agreeable companion . . . good-humoured and vivacious.” James Boswell to David Dalrymple, August 2, 1763, Chauncey Brewster Tinker, ed., Letters of James Boswell, vol. 1: July 29, 1758-November 29, 1777 (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1924), 40. [↩]

- Edward Gibbon, Miscellaneous works of Edward Gibbon, Esquire 1: 100 [Journal entry for September 23, 1762].] [↩]

- Thomas Sadler, ed., Correspondence of Henry Crabb Robinson (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1898), 238. This boast was apparently one of Wilkes’ favorite witticisms. Admiring historians who pass it off as jest ignore the degree to which Wilkes libeled his opponents. [↩]

- [John Wilkes], The North Briton. Revised and Corrected by the Author, vol. 1 (Dublin: John Mitchell and James Williams, 1764), 80 [No. 15], 231 [No. 40]. [↩]

- [John Wilkes], The North Briton. Revised and Corrected by the Author, vol. 1 (Dublin: John Mitchell and James Williams, 1764), 263 [No. 45]. [↩]

- [John Wilkes], English Liberty: Being a Collection of Interesting Tracts, From the Year 1762 to 1769. Containing the Private Correspondence, Public Letters, Speeches and Addresses, of John Wilkes, Esq. Humbly Dedicated to the King (London: Printed by and for T. Baldwin, [1769]), 87. [↩]

- On the prints in Wilkes’ home in Westminster, see The Reminiscences of Henry Angelo, with memoirs of his late father and friends, including numerous curious anecdotes and curious traits of the most celebrated characters that have flourished during the last eighty years (2 vols., London: Kegan Paul, Trench,Trübner & Co., 1904 [originally published London: Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley, 1830]), 1: 42. [↩]

- In his Epistle, Churchill included a poetic description of Hogarth sketching Wilkes in court:

Lurking, most Ruffian-like, behind a screen,

So plac’d all things to see, himself unseen,

VIRTUE, with due contempt, saw HOGARTH stand,

The murd’rous pencil in his palsied hand.

What was the cause of Liberty to him,

Or what was Honour? let them sink or swim,

So he may gratify without controul

The mean resentments of his selfish soul.

Let Freedom perish, if, to Freedom true,

In the same ruin WILKES may perish too.Charles Churchill, An Epistle to William Hogarth (London: Printed for the author and sold by J. Coote, 1763), 20. Several writers joined in the fray, some in imitation of Churchill. See Joseph M. Beatty, Jr., “The Political Satires of Charles Churchill,” Studies in Philology, vol. 16, no. 4 (October 1919), 303-33. esp. 320-25. “The Bruiser” is a visual allusion to Hogarth’s witty self-portrait, now in the Tate Britain, in which his beloved dog Trump is the central figure and Hogarth is depicted in an oval portrait within the painting. [↩]

- Zoffany’s Hogarth prints were sold in the sale of Zoffany’s estate in 1811 — see Manners and Williamson, John Zoffany, R.A, 288 for the inventory; Queen Charlotte, who had a private collection of eighty-four Hogarth prints, also owned these works. Queen Charlotte’s Collection of Hogarth Works is in The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University. [↩]

- Many who viewed the image reacted as Hogarth seems to have intended. “Philo-Britannicus,” wrote, as if addressing Wilkes: “I have seen a print of you here, holding up a cap with the word LIBERTY upon it, and a Devil your familiar, prompting your North-Briton into your ear. The device, I think, really is a just and a very pretty one; only that you are a most shocking dog to look at, and ought not to be exposed to pregnant women’s view, as they are in use (like Laban’s cattle) to copy what strikes their fancy. Your face is the indication of a very bad soul within; and any, the least judge of physiognomy, may see you a scoundrel at one view.” [Philo-Britannicus], A Letter from Scots Sawney the barber, to Mr. Wilkes an English Parliamenter (Boston: [Zechariah Fowle], 1763). On the embrace of the image by Wilkes’ supporters, see Shearer West, “Wilkes’s Squint: Synecdochic Physiognomy and Political Identity in Eighteenth-Century Print Culture,” Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol. 33, no. 1 (1999): 65–84, to which I owe my reference to “Philo-Britannicus.” On the 1770 masquerade, see Horace Walpole to Horace Mann, February 27, 1770, Mrs. Paget Toynbee [Helen Wrigley Toynbee], ed., The Letters of Horace Walpole, Fourth Earl of Orford, vol. 7: 1766-71 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1904), 366-60. [↩]

- Benjamin Franklin to William Temple Franklin, April 16, 1768, William B. Willcox, ed., The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 15: January 1-December 31, 1768 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1972), 98-99. [↩]

- Benjamin Franklin reported to his son that “the mob” was “requiring gentlemen and ladies of all ranks as they passed in their carriages to shout for Wilkes and liberty, marking the same words on all their coaches with chalk, and No. 45 on every door; which extends a vast way along the roads into the country. I went last week to Winchester, and observed that for fifteen miles out of town, there was scarce a door or window shutter next the road unmarked; and this continued here and there quite to Winchester, which is 64 miles.” Benjamin Franklin to William Temple Franklin, April 16, 1768, Willcox, ed., Papers of Benjamin Franklin, 15: 98-99. [↩]

- Brewer, Party Ideology, 178 [↩]

- Brewer, Party Ideology, 191; Wraxhall added that “In the House of Commons he was not less an actor than at the Mansion House or at the Guildhall.” Henry B. Wheatley, ed., The Historical and Posthumous Memoirs of Sir Nathaniel William Wraxhall, 1772-1784 (5 vols., London: Bickers & Son, 1884), 2: 48. [↩]

- Brewer, Party Ideology, 185, 190; Lord Weymouth reported to the king on May 6, 1768, that sailors protesting for higher wages “disclaim Wilkes”; Fortescue, ed., Correspondence of George III, 2: 23. [↩]

- The “Queen’s house” was Buckingham House, only recently purchased by the king as a city residence for the queen. It is now, having been considerably enlarged, Buckingham Palace. Thomas Whately to George Grenville, April 18, 1768, William James Smith, ed., The Grenville Papers: Being the Correspondence of Richard Grenville Earl Temple, K.G., and the right honorable George Grenville, their Friends and Contemporaries (4 vols., London: John Murray, 1853), 4: 267-71; the passage quoted is on p. 268; The king called Wilkes’ expulsion “very essential.” George III to Lord North, April 25, 1768, Fortescue, ed., Correspondence of George III, 2: 21. [↩]

- For an account of the riot, see The Political Register, vol. 4 (April 1769), 254-56. [↩]

- James Brydges, duke of Chandos, to George Grenville, March 23, 1768, Smith, ed., The Grenville Papers, 4: 415-17; Lord Holland’s description is in George Otto Trevelyan, The Early History of Charles James Fox (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1881), 178, note 1; Thomas Whately to George Grenville, March 25, 1769, Smith, ed., The Grenville Papers, 4: 417-18. [↩]

- George III to Lord North, March 20 and March 21, 1771, Fortescue, ed., Correspondence of George III, 2: 235, 235-36; John Calcraft to the Earl of Chatham, March 24, 1771, William Stanhope Taylor, Correspondence of William Pitt, Earl of Chatham, vol. 4 (London: John Murray, 1840), 122-23; On the king’s growing prudence with regard to Wilkes, see Roberts, Last King of America, 215. [↩]

- On Zoffany’s social life in London, see the chatty, name-dropping memoir of Henry Angelo, the son of Domenico Angelo, who operated a well-known fencing school in London in the 1760s and 1770s. Wilkes, Garrick, and others, including Zoffany, were frequent guests of the Angelos. Reminiscences of Henry Angelo, with memoirs of his late father and friends, including numerous curious anecdotes and curious traits of the most celebrated characters that have flourished during the last eighty years (2 vols., London: Kegan Paul, Trench,Trübner & Co., 1904 [originally published London: Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley, 1830]), 1: 106-9, 112, 133-35, 268, 280, 2: 82 (the characterization of Zoffany as “very ugly.”); On the self-portrait with a monk’s habit, see Treadwell, Zoffany, 289, 293. [↩]

- The “line of beauty” is a central theme of William Hogarth, The Analysis of Beauty: Written with a view of fixing the fluctuating Ideas of Taste (London: printed by J. Reeves for the author, and sold by him at his house in Leicester-Fields, 1753). [↩]

- Penelope Treadwell makes no mention of Hogarth’s caricature of Wilkes in this context, though she includes it as an illustration in connection with Zoffany’s 1779 portrait of Wilkes and his daughter. She contends that the “nothing about this 1771 portrait of George could have been more calculated to run counter to the King’s taste in portraiture” and that Zoffany planned and executed the portrait to suit himself, “damn the consequences. (Treadwell, Zoffany, 130); on Wilkes as a jester, see Brewer, Party Ideology, 190-91. [↩]

- James Boswell, who met Mary Knowles, is the source of the amount if the queen’s gift. See William K. Wimsatt, Jr. and Frederick A. Pottle, eds., Boswell for the Defense, 1761-1774 (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc, 1959), 36. [↩]

- Treadwell, Zoffany, 300-2. Zoffany’s The Tribuna of the Uffizi is in the Royal Collections Trust. [↩]

- Horace Walpole to Lady Ossury, November 14, 1779, L.B. Seeley, ed., Horace Walpole and his World: Selected Passages from His Leters (London: Seeley, Jackson, and Halliday, 1884), 162. [↩]