The American revolutionaries rejected monarchy, aristocracy, and religious establishments, the defining institutions of the old regime. They expressed ideals — independence, liberty, equality, natural and civil rights, and responsible citizenship under the rule of law — that became the defining principles of American life and are embraced by men and women around the world who want to enjoy the benefits of freedom. The American Revolution led directly to liberal democracy, released the creative energy of the American people, and created conditions that helped make the United States an engine of global economic development.

The American Revolution was a dramatic break with the past, but the protest movement that led to the Revolution did not begin that way. Opposition to new taxes and more energetic imperial regulation began as a defense of privileges and liberties colonial British Americans had long enjoyed. It drew on practices and ideas that were centuries old. In the beginning colonists appealed to convention and expressed their frustration in traditional ways.

Under the pressure of events these ideas and practices were reshaped. This change was reflected in the formal arguments of colonial gentlemen, who were driven by the logic of their British opponents to abandon their reliance on traditions of English liberty and colonial autonomy and adopt a position based on universal principles of natural right. It was also reflected in the actions of ordinary colonists who were driven by the intransigence of customs agents, colonial officials, and imperial bureaucrats to reshape traditional forms of popular protest. Divisions grew deeper, rhetoric more strident, and protests more violent.

These changes did not happen all at once, nor did they happen at the same pace nor in the same way everywhere in the colonies. But the pressures driving them were felt, in different ways, throughout British America. They were reflected in events that marked the transition from protest and resistance to rebellion and revolution. Consider, for example, the events of January 25, 1774, when an angry mob dragged John Malcom from his house in Boston, stripped off his clothes, and coated him with tar and feathers.

“extortions & depredations & violence”

John Malcom was one of many people subjected to tarring and feathering during the Revolutionary era, but his ordeal was the most widely known and discussed episode of the kind and has left us with more evidence than any other. Through it we get a glimpse of how American colonists reshaped old ideas and practices and became, in the process, American revolutionaries.

Malcom is not a very sympathetic figure. In the surviving documentation he comes across as a haughty, humorless, mean-spirited man, quarrelsome and bad tempered. He was born in Boston in 1723 to recent Scots-Irish migrants. As a young man he served with provincial troops in King George’s War. At twenty-two he was an ensign at the Siege of Louisbourg. He later served in the French and Indian War. In the petition he laid before King George III in 1774 he boasted that he had held thirteen separate military commissions in the royal service and had been in nearly every battle fought in North America during those wars.1

John Malcom spent most of his career as a Boston sea captain — owner or part owner of a variety of small merchant vessels trading in the Caribbean, Nova Scotia, New York, and the Carolinas. In 1769 he secured an appointment as a tide surveyor in Newport, Rhode Island. A tide surveyor was a customs official who watched for arriving vessels, boarded them to look for smuggled goods, and ensured that cargoes were properly landed and documented and the duties collected. Under the best circumstances a tide surveyor was apt to be unpopular in Rhode Island, where smuggling was a way of life, but Malcom made himself particularly obnoxious. Merchants despised him, but so did ordinary tradesmen. On one occasion a butcher and on another a baker had to take Malcom to court to make him settle his accounts.

In February 1770 Malcom sought to take communion at the First Congregational Church in Newport. Though the congregation conventionally allowed visitors from other Protestant churches to join in communion, its leaders rebuffed Malcom. “The scruple arose on his Morals,” Reverend Ezra Stiles wrote in his diary, “which are exceptionable.” Exactly what Malcom did to merit this assessment is not clear, but he had worn out his welcome. In 1771 he left Rhode Island behind, having secured an appointment as comptroller of customs in Currituck County, North Carolina.2

Malcom arrived in North Carolina just as the colony was degenerating into violence. The people of the North Carolina backcountry were frustrated by high taxes, corrupt officials, scanty representation in the assembly, and difficulty in securing clear title to their land. Frustration had turned to protest and finally open resistance by colonists calling themselves Regulators. In the spring of 1771 Governor William Tryon, having decided to put down the backcountry rebellion by force, raised some 1,300 militia in the eastern counties and marched them west to Hillsborough in the heart of Regulator country. John Malcom went with Tryon as a volunteer aide.3

On May 14, 1771, the governor’s army reached Alamance Creek, west of Hillsborough, where some two thousand armed Regulators were gathered. Tryon offered to pardon them if they surrendered their leaders for trial, laid down their arms, and swore their allegiance to the king. They declined. On May 16 the governor’s army approached the Regulator camp. Tryon sent Malcom to repeat his offer. The Regulators, according to a witness, “rejected the Terms offer’d with disdain, said they wanted no time to consider of them and with rebellious clamor called out for battle.”4

Malcom, who did not lack courage of a sort, rode back to the army’s lines. Then Tryon ordered his cannons to open up on the Regulators, who hid behind trees and fired on the gun crews. After two hours the Regulators ran low on ammunition and fled, leaving behind hundreds of dead and wounded. Tryon’s army took hundreds of prisoners. The governor ordered one of them hanged the day after the battle and put twelve others on trial for treason. Six of them were executed. Tryon praised Malcom, who was no doubt well satisfied with the outcome.

As a reward the Crown appointed William Tryon royal governor of New York. The ministry sent Josiah Martin, an ambitious young man, to take Tryon’s place in North Carolina. Martin found conditions in the colony were far worse than reported. Customs officials were corrupt and county officials were just as bad as the Regulators claimed. Among the worst, Martin concluded, was John Malcom, whom he described as a “hair brained” bully, guilty of “extortions & depredations & violence” against His Majesty’s subjects “under colour of performing his duty.” Martin removed him from the customs office, reporting to London that he had sent depositions documenting Malcom’s “venality and corruption as well as extortion” to the commissioners of customs in Boston.5

This might have been the end of John Malcom’s employment in His Majesty’s customs service, but bureaucracy intervened. Governor Martin, it turned out, had no authority to remove a customs official. That authority resided in the commissioners of customs in Boston, who promptly appointed Malcom comptroller in Falmouth on the coast of Maine. There he made it clear that the reputation he had earned in Newport and North Carolina was well deserved.6

On October 21, 1773, he seized a merchant brig loading a cargo of lumber because of a narrow, technical irregularity in its paperwork. According to a newspaper report of the affair, he went aboard the vessel, “threatened to sheath his sword in the bowels of any one who dared dispute his authority, and in fact cut some tackling with which some timber was hoisting, by which means three or four people narrowly escaped instantaneous death.”7

On November 1 a party of thirty sailors pulled Malcom out of a house, took his sword, cane, hat, and wig, and then coated him — over his clothes — in tar and feathers. After marching Malcom through the streets for an hour and forcing him to swear not to seize any more vessels, they released him.8

“ignomious Dress”

No one in modern memory has been tarred and feathered in the eighteenth-century manner. Indeed most people seem to misunderstand what was involved and think that victims of tarring and feathering were coated with boiling hot liquid, which was not the case.9

Tar is a liquid extracted from pine by heating it in a dense pile deprived of oxygen to prevent the wood from catching fire. Under these controlled conditions the pine resin melts and runs off as a viscous, strong-smelling, sticky liquid with the consistency of motor oil or light syrup, liquid at room temperature. It dries like varnish when applied and does not need to be heated for use except in very cold weather, when it might be warmed up a little to thin it, but most people subjected to tarring and feathering were coated with tar just as it came from the barrel, at whatever the ambient temperature was at the time. The tar was usually applied with a brush or a bucket and mop of the sort used to coat decks.10

When tar is heated to a sustained boil it thickens and becomes pitch, which hardens to a waterproof solid when it cools. Pitch was used to seal the joints between planks and other ships’ timbers. Boiling tar to make pitch was a common activity in shipyards because pitch has to be used immediately or it hardens in the pot. Pitch made by boiling tar and cooling it was sold in solid chunks that had to be reheated to near boiling for use. People who were tarred and feathered were coated with tar, not pitch. Anyone coated with pitch would have sustained very serious and probably fatal burns.

The idea that people were tarred with a boiling hot liquid seems to have taken hold because the word tar is now commonly, though improperly, applied to asphalt used to pave roads. Asphalt is a petroleum byproduct that must be heated for use. Anyone coated with hot asphalt would suffer life-threatening burns. Victims of tarring and feathering were not burned, but they were often injured in others ways. They were sometimes beaten, but tar and feathers were applied to humiliate and intimidate rather than injure them — and above all else to serve as a warning to others.

Tarring and feathering belongs with a class of late medieval and early modern customs through which ordinary people participated in the regulation of society, usually to maintain norms. The practice is related to charivaris — processions in which people harassed and paraded offenders accompanied by the rough music of banging pots, cowbells, and primitive horns — and skimmingtons, processions intended to ridicule henpecked husbands, shrewish wives, and notorious adulterers.11

In this 1726 depiction of a skimmington by William Hogarth, a shrewish wife and her cuckold husband (mounted at left) are the objects of ridicule. She threatens him with a skimming ladle and rides sitting forward. He rides backward and holds a distaff, a symbol of women’s work. Villagers make rough music — one swings a cat by its tail to make it howl — and carry makeshift banners, one topped by horns, symbolizing a husband whose wife’s adultery has “put the horns on him.” A tailor laughs as the procession passes his shop, oblivious to his wife making the horns over his head, indicating that she is unfaithful to him — probably with the man watching from below who shows his contempt for the tailor by urinating on the shop wall. Metropolitan Museum of Art

The objects of these rituals were usually made to join the procession and might be forced to ride backward on a horse or donkey or to ride on a rail or log carried by the crowd. Costumes were sometimes involved. A bullied husband might be forced to wear a dress and participants might wear masks or don mock symbols of authority — imitation judge’s wigs, sashes, or crowns. Objects of humiliation might be arrayed as animals or forced to crawl on all fours like beasts of burden. These were public spectacles intended to warn others that violating traditional norms carried a heavy price.

The origins of these rituals are lost and most undoubtedly consist of layers from various sources added over time. They bear comparison with medieval religious processions and the social inversions characteristic of medieval and early modern carnivals and revel feasts. Some of those layers were drawn from customs employed at sea to maintain order among men thrown together in close quarters for long periods of time. Hazing, like the familiar mock trials and humiliations imposed on sailors crossing the equator for the first time, reinforced traditional hierarchies. Most such rituals, indeed, tended to uphold traditional orders rather than subvert them. They were not acts of rebellion. Only a few elements of these rituals — burning in effigy is one — have survived into modern times. Most that do are understood as anachronisms.

“the confused Object of their Ridicule”

Colonists brought these customs to America, where they served the same purposes as in Britain. Americans marked Pope’s Day, or Guy Fawkes’ Day, with bonfires and processions in which the Pope, the devil, and other figures were burned in effigy. In 1764 Bostonians staged a skimmington to chastise a notorious adulterer. During the Regulator unrest in North Carolina, when a Sheriff Hawkins seized a farmer’s mare for unpaid taxes, a crowd of the farmer’s neighbors seized the sheriff, took him to Hillsborough, and made him ride backward on a horse through the town to the accompaniment of rough music.12

The use of tar in such rituals almost certainly began with sailors, boat builders, and dock workers, for whom tar was a familiar water repellent and wood and rope preservative. Barrels of tar were common in shipyards and on wharves and sailing vessel, both for use and as a product for export. Tar produced in the colonies was shipped all over the Atlantic world. Sailors were commonly referred to as ‘tars’ because they handled the stuff so much and must have smelled like it. An incident reported in a New York newspaper in 1743 makes it clear that sailors had used tar to humiliate for decades:

Saturday last the Men belonging to the Castor and Pollux Privateers, having found that a Person who had entered on board them two or three Days before, in order to go the Cruize, was a Woman, they seized upon the unhappy Wretch and duck’d her three Times from the Yard-Arm, and afterwards made their Negroes tarr her all over from Head to Foot, by which cruel Treatment, and the Rope that let her into the Water having been indiscreetly fastened, the poor Woman was very much hurt, and continues now ill.13

That the victim in this case was a woman trying to pass as a man was probably what made the incident noteworthy. It seems likely that tarring was a common ritual punishment at sea. The report makes no mention of feathers, which would have been in short supply on sailing vessels. The addition of feathers is mentioned in a few earlier accounts of tarring. In a 1741 description of Jamaica, the author mentions the use of tarring and feathering as a punishment for disobedient slaves. Clearly the use of feathers was not new on the eve of the American Revolution, but the practice was not familiar to most. Henry Hulton, who arrived in Massachusetts as commissioner of customs in November 1767, described tarring and feathering as “a new invention.”14

Tar was a feature of shipboard rituals in the eighteenth century. In this 1788 watercolor by Julius Caesar Ibbeston, sailors dressed as Neptune and his royal concubine preside over the traditional hazing ritual carried out when HMS Vestal crossed the equator on its way to China. A sailor at right stands ready with a tar bucket and brush to daub anyone aboard crossing the line for the first time. Yale Center for British Art

The first report of tarring and feathering in the Revolutionary era comes from William Smith, a merchant who lived in Portsmouth, Virginia. Smith crossed the Elizabeth River to neighboring Norfolk on April 3, 1766, and was promptly seized by men who accused him of informing on a fellow merchant who had been charged with smuggling. Smith reported that

they bound my hands and tied me behind a Cart . . . . hurried me to the County Wharf and bedawbed my body and face all over with tar and afterwards threw feathers upon me; they put me upon a Ducking Stool and threw rotten eggs and stones at me . . . they carried me through every street in the town . . . . Afterwards they carried me back to the Market House with two drums beating, shewing all imaginable demonstrations of joy . . . . At last they loosed me . . . and threw me headlong over the wharf, where I was in imminent danger of being drowned, had not a boat taken me up when I was just sinking, being able to swim no longer.15

The humiliating procession through the town on a stool, the rough music, and the “demonstrations of joy” were all part of the old tradition of charivaris and skimmingtons. But the tar and feathers were not. They must have been part of a sailors’ tradition grafted on to the old forms of ritual humiliation, because they appeared in 1768 in a port town several hundred miles away. On September 12, The Boston Chronicle reported:

We hear from Salem, that a person there having given information of a vessel that arrived there with molasses, the populace were so enraged, that they stript him, then wrapped him in a tarred sheet, and rolled him in feathers; having done this they carried him about the streets in a cart, and then banished him [from] the town for six weeks.16

Most of the elements of the Norfolk incident were there — the victim was an informer and was tarred and feathered and paraded through the town in a cart — but it seems very unlikely that that the people in Salem knew anything about the incident in Norfolk or were inspired by it, even indirectly. It seem more likely that sailors were involved in both incidents and adapted customs used at sea.17

The Salem crowd tarred and feathered a tidewaiter — a minor customs official — a few days later. This time they applied warm tar, coated the victim with feathers “which by closely adhering to the Tar, exhibited an odd Figure, the Drollery of which can easily be imagined.” Then they attached signs reading “Informer” on his front and back and paraded “the confused Object of their Ridicule” through town to the delight of a large and boisterous crowd.18

At least a dozen more incidents of tarring and feathering following this general pattern occurred Newburyport, Marlborough, Gloucester, Boston, New Haven, New York, and Philadelphia by March 1770. The victims were informers or customs officials, with two known exceptions. In Marlborough the victim was a horse, coated with tar and feathers as a warning to its owner. In November 1769 Bostonians tarred and feather a man who had enticed a young woman into a British barracks where she was “most shamefully abused by some of the soldiers.” They put him in a cart, applied tar and feathers — “the present popular Punishment for modern delinquents” — and carted him around Boston for two or three hours “as a Spectacle of Contempt and a Warning to others from practicing such vile Artifices for the Delusion and Ruin of the virtuous and innocent.” The connection between tarring and feathering and skimmingtons was most explicit in New Haven, where an informer was tarred and feathered over a frock supplied by townspeople, who completed his “ignomious Dress” by “fixing a Pair of Horns on his Head.”19

After 1770 the victims of tarring and feathering were more often merchants who violated non-importation agreements than informers or customs officials, but everywhere the practice served as a warning to discourage others from violating the sense of their community and the interests of its people. When the sailors of Falmouth tarred and feathered John Malcom over his clothes then marched him around the town, they were warning him and his colleagues in the customs service not to interfere with their livelihood.

“a sudden heat”

John Malcom returned to Boston to complain about the humiliating attack. He was in the city when patriots threw the East India Company’s tea into the harbor and openly expressed his contempt for those involved. Malcom complained to Governor Thomas Hutchinson about “being hooted at in the Streets for having been tarred and feathered.” The governor cautioned him “against giving way to his Passion,” to no avail. On January 25 — a brutally cold winter day, even for Boston — Malcom encountered a young boy in the street, pushing a sled. The boy may have said something that infuriated Malcom. A newspaper reported that the boy had run over Malcom’s foot with his sled.20

What happened next is not entirely clear. John Adams wrote that Malcom “attacked a lad in the street, and cut his head with a cutlass, in return for some words from the boy, which I suppose were irritating. The boy ran bleeding through the street to his relations, of whom he had many. As he passed the street, the people inquired into the cause of his wounds; and a sudden heat arose against Malcolm.” Malcom’s superior in Falmouth heard it that way, too, and wrote that what happened to Malcom “was occasioned by his beating a Boy in the Street in such a manner as to raise a Mob.”21

The account of the incident published in the Massachusetts Gazette was slightly different. It reported that a Boston shoemaker, George Hewes, came upon Malcom “cursing, damning, threatening and shaking a very large cane” at the boy. Hewes intervened and Malcom turned on him, calling Hewes an “impertinent rascal.”22 The confrontation quickly escalated, and Malcom struck Hewes with the cane, gashing his forehead. Hewes fell to the ground, bloody and unconscious. A Captain Godfrey saw of the attack and “after some altercation” Malcom retreated to his house. Bystanders took Hewes to Dr. Joseph Warren, who dressed the wound and joked grimly with his patient about his thick skull. “Nothing else could have saved you.” The deep scar left by the cane was clearly visible when Hewes died more than sixty-six years later.23

The newspaper account says nothing more about the child. Perhaps Malcom struck him, too, as Adams reported. Or perhaps when Hewes arrived, the boy ran. In any event, after Dr. Warren dressed his wound Hewes complained to a justice of the peace who issued a warrant for Malcom’s arrest. The constable sent to Malcom’s house either did not find him there or agreed to return the next day.24

Whatever happened with the child and the constable, the story spread. That night a mob attacked Malcom’s house, broke in through a second story window and dragged him into the street, where they beat him and threw him into a sleigh.25

When they reached King Street, near the site of the Boston Massacre, unnamed “gentlemen” tried to convince his captors to let Malcom go, assuring them that the courts would punish him. The mob, which by then numbered in the hundreds, was unmoved. What had the courts done to punish Preston or his men for the killings in King Street? What had they done to punish Ebenezer Richardson, a customs official who had shot and killed a young boy outside his house? Malcom, they said, “had joined in the murders at North-Carolina” and behaved in a “daringly abusive manner” without being punished. The law had had its chance.26

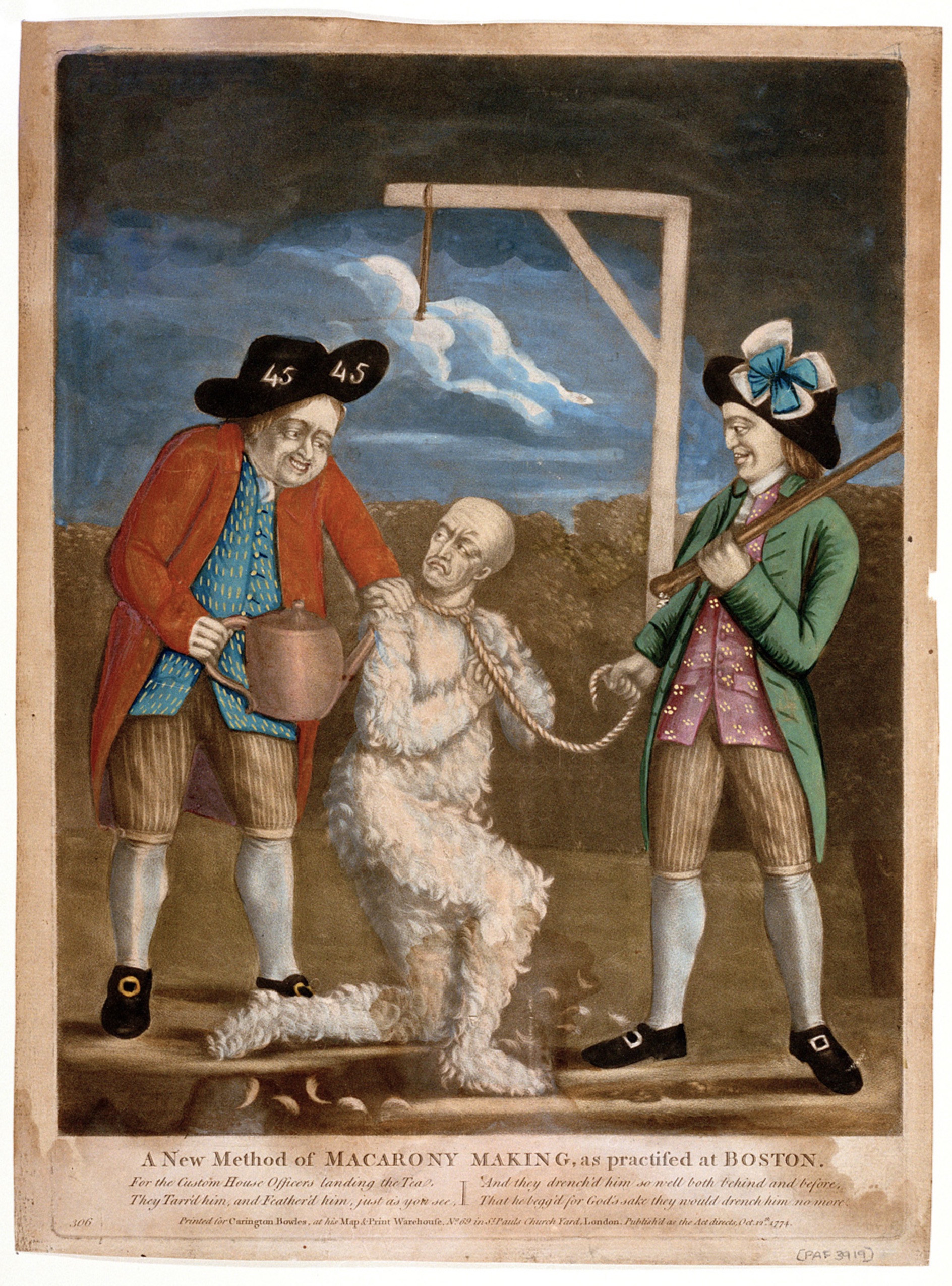

Carrington Bowles of London published this mezzotint of the tarring and feathering of John Malcom on October 12, 1774. Malcom had gone to England seeking compensation for his ordeal, contending that he was attacked because he had criticized the destruction of the tea in Boston. To draw attention to his appeal he announced that he would stand for election to Parliament against John Wilkes. The print depicts one of Malcolm’s tormentors wearing pins with the number 45 — a mark of Wilkes’ supporters — in his hat. The title of the print refers to macaronis, a slang term for dissolute, effeminate men who affected the latest fashions. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, England

They put Malcom in a cart, stripped him to his breeches, and coated him with tar and feathers — “a modern jacket,” the Massachusetts Spy called it. None of the accounts suggests that the tar was hot or that Malcom was burned. Indeed the night was so cold that he suffered frostbite. The crowd drove him to the Liberty Tree where his tormentors demanded he renounce his office and according to a report friendly to Malcom, ordered him to curse the king and the governor. Malcom stubbornly refused, so they drove him through the city to the gallows near Boston Neck and threatened to hang him.27

Along the way, according to another report, the mob forced Malcom to drink hot tea until he vomited, taunting him to drink to the royal family. When he still defied the mob, they beat and whipped him and threatened to cut off his ears. Broken, Malcom finally gave up and agreed to do whatever the mob wanted. His tormentors carted him through the streets and dumped him in front of his house in what Malcom described as “a most mizerable setuation Deprived of his senses.”28

“Anarchy will continually increase”

John Malcom had the distinction of being tarred and feathered twice, but his case was unusual in other ways that illustrate the changing nature of colonial resistance. The deed that roused the mob in Boston had nothing to do with customs enforcement, violating non-importation agreements, or collecting taxes — at least not explicitly. The mob had reacted to an incident in the street in which a despised customs official threatened or struck a boy with his heavy cane and then struck and nearly killed an artisan with many friends.

There was nothing premeditated about the incident. If other tarrings and featherings were directed or encouraged by patriot leaders, this one was not — at least there is no evidence of their involvement. Moderate Bostonians who had regarded earlier episodes of tarring and feathering with indifference or even wry amusement were appalled by the mob’s treatment of Malcom. Merchant John Rowe wrote that it “was looked upon by me and every sober man as an act of outrageous violence, and when several of the inhabitants applyed to a particular justice to exert his authority and suppress the people and they would support him in the execution of his duty, he refused.”29

Patriot leaders were quick to insist that they had nothing to do with the incident and did not countenance it. This was impossible to prove since they operated in secret and generally relied on intermediaries and pseudonyms to disguise their activities. Under a pseudonym for the chairman of a fictitious “Committee for Tarring and Feathering” they posted handbills and ran newspaper notices certifying “that the modern Punishment lately inflicted on the ignoble John Malcom, was not done by our Order.” Gentlemen, they said in another notice, had tried “rescuing Malcom from the modern mode of punishment” but found that he fallen “into the hands of a great number of sailors, from the Eastward and other parts, whom he had so often exasperated that nothing could soften them.” If the incident had occurred in isolation they might not have worked so hard to distance themselves from the incident, but coming so soon after the destruction of the tea it was bound to be linked in the minds of British ministers and colonial administrators with that event.30

Not to be outdone by their competitor Carrington Bowles, Sayer and Bennett of London published this fanciful mezzotint of Malcolm being forced to drink tea after being tarred and feathered. The depiction of colonists dumping East India Company tea in the background is the first published image of what became known as the Boston Tea Party. A tar bucket and mop are in the left foreground. Both prints mistakenly connected the mob’s outrage at Malcom to the excise on tea. John Carter Brown Library

The crowd did not share this concern. The attack was linked, in the minds of many in the mob, with the killing of ten-year-old Christopher Seider by a customs officer in 1770. The perpetrator, Ebenezer Richardson, had fired bird shot at boys throwing dirt clods, eggs, rocks, and trash at his house. Shot lodged in Christopher’s lungs and he died after suffering for several hours. Richardson was convicted of manslaughter then pardoned by the king, which outraged Bostonians. When “gentlemen” tried to intervene and persuade the mob to let the law deal with Malcolm, people in the crowd reminded them that the law had done nothing to punish Richardson.31

In this way the tarring and feathering of John Malcom was not so much a ritual to reinforce traditional values — in most cases the solidarity of a community dependent on the sea — as an extra-judicial punishment imposed because government had failed to uphold laws when government agents were the transgressors. This may account for the particularly brutal way Malcom was treated, which was more like a lynching than a charivari or a skimmington. The ritual of tar and feathers did not, in this case, uphold traditional norms beyond those provided for in law. The ritual was a form of rough justice — not where the law had failed, as it had failed to punish Christopher Seider’s killer — but where the mob expected the legal system to fail. The difference was subtle but unmistakable. The tarring and feathering of John Malcolm was the act of people who had lost faith in their government as an instrument of justice. It didn’t lead inevitably to revolution, but it was an act of rebellion that demonstrated the people’s growing disdain for their government.

As if to underscore the popular disgust with government, the night after Malcom was tarred and feathered, according to merchant John Rowe, “a great concourse of people were in quest of the infamous Richardson . . . . They could not find him,” Rowe wrote, adding “very lucky for him.”32

Contemporaries recognized the change. The Massachusetts Spy concluded its account of Malcom’s ordeal with a warning: “See reader, the effects of a government in which the people have no confidence!” Governor Hutchinson, a perceptive observer, doubted that popular confidence in the government would soon return. “I rather think the Anarchy will continually increase,” he wrote Lord Dartmouth three weeks after the attack on Malcolm, “until the whole Province is in confusion.”33

Malcom did not remain in America to witness the Revolution that resulted from all that anarchy and confusion. In May he left his wife and five children and sailed for London, never to return. He petitioned the king for compensation and the king’s ministers for a more lucrative appointment in the customs service, proudly exhibiting patches of tar and feathers he had peeled off with his dried, frostbitten skin as evidence of his loyalty. After many months he was made an ensign in an invalid regiment — an appointment that paid sixty pounds a year for no work — and secured a pension of one hundred pounds a year. In 1782 the commissioners on loyalist claims decided his pension was too large, but they continued it, according to their report, “in Consideration of his Sufferings & more particularly because he appears to us to be in some degree insane.”34

Notes

- John Malcom was descended from the Clan Malcolm of Scotland, but he wrote his name “Malcom.” It appears that way in most contemporary sources, though William Tryon, Thomas Hutchinson, and others with whom he interacted spelled his name “Malcolm.”

Malcom’s petition to the king, January 12, 1775, seeking compensation for his suffering in the king’s service and reinstatement in the customs is calendared in Benjamin F. Stevens, comp., The Manuscripts of the Earl of Dartmouth, vol. 2 [American Papers] (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1895), 263, as an enclosure to Malcom to Lord Dartmouth, January 31, 1775. Frank W. C. Hersey transcribed the manuscript and included it in “Tar and Feathers: The Adventures of John Malcom,” Transactions of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, vol. 34 (April 1941), 433. The product of long research, this article includes reports, petitions, correspondence, and other material about Malcom from collections in the United States and Britain. [↩]

- Franklin B. Dexter, ed., The Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles, vol. 1 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1901), 39 [February 24, 1770]. [↩]

- On the unrest and Tryon’s response, see Marjoleine Kars, Breaking Loose Together: The Regulator Rebellion in Pre-Revolutionary North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002). [↩]

- “Journal of the Expedition Against the Insurgents in the Western Frontier of North Carolina, Begun the 20th April, 1771,” Walter Clark, ed., State Records of North Carolina, vol. 19 (Goldsboro: Nash Brothers, 1901), 843-45. [↩]

- Josiah Martin to Samuel Johnston, February 6, 1772, Josiah Martin to Wills Hill, marquis of Downshire [Lord Hillsborough], June 5, 1772, William L. Saunders, ed., Colonial Records of North Carolina, vol. 9 (Raleigh: Josephus Daniels, 1890), 236-37, 299-300; see also Vernon O. Stumpf, “Josiah Martin and His Search for Success: The Road to North Carolina,” North Carolina Historical Review, vol. 53, no. 1 (January 1976), 55-79. [↩]

- Tryon had probably intervened on Malcom’s behalf. Ann Hulton, the wife of a British commissioner of customs at Boston, later wrote that Malcom “was with Govr Tryon in the Battle with the Regulators & the Governor has declared that he was of great servise to him in that affair, by his undaunted Spirit encountering the greatest dangers,” adding that Tryon had sent Malcom a gift of ten guineas just before he was tarred and feathered in Boston. Ann Hulton to Mary Ewing Lightbody [Mrs. Adam Lightbody], January 31, 1774, [Ann Hulton], Letters of a Lady Loyalist: Being the Letters of Ann Hulton, sister of Henry Hulton, Commissioner of Customs at Boston, 1767-1776 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1927), 69-72. [↩]

- Boston Gazette, February 14, 1774; The vessel was subsequently condemned by a British admiralty court and Malcom received one hundred pounds as his share of the value of the ship and its cargo. [↩]

- Boston Gazette, November 15, 1773. Massachusetts Governor Thomas Hutchinson alluded to this incident in more sympathetic terms: “I have heard no Complaint of any Irregularity in this execution of his Office, but a great number of Persons in that part of the Province thought fit to punish him by tarring & feathering him, and carrying him about in Derision. As he was not stripped, and the chief Damage sustained was in his Cloaths, upon his making complaint to me I only sent for one of the principal Justices of the Peace for the County, & directed him to make Inquiry into the Affair . . . .” Hutchinson to Lord Dartmouth, January 28, 1774, John W. Tyler, et al., eds., The Correspondence of Thomas Hutchinson, vol. 5 July 1772-May 1774 (Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 2023), [vol. 99 of the Publications of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts], 424-26. [↩]

- The otherwise excellent HBO series John Adams erroneously depicts a customs official being coated with hot pitch and then being paraded around while clutching a rail. Anyone coated with hot pitch in this way would have sustained life-threatening burns and would have been unable to stand. [↩]

- On American tar production and use in the eighteenth century, see Mikko Airaksinen, “Tar Production in Colonial North America,” Environment and History, vol. 2, no. 1 (February 1996), 115-25. Airaksinen notes that when tar was used as a rope preservative it was warmed to a thin consistency that would penetrate the fibers. Otherwise it was mostly used at the ambient temperature; In his 1781 manuscript “Origin and Progress of the American Rebellion” loyalist Peter Oliver described tarring and feathering, including heating the tar “until thin,” but his description is a lurid exaggeration and includes setting the feathers on fire — a practice for which there is no evidence. Oliver wrote: “First, strip a Person naked, then heat the Tar untill it is thin, & pour it upon the naked Flesh, or rub it over with a tar brush, quantum sufficit. After which, sprinkle decently upon the Tar, whilst it is yet warm, as many Feathers as will stick to it. Then hold a lighted Candle to the Feathers, & try to set it all on Fire; if it will burn so much the better.” Oliver erroneously reported wrote that tarring and feathering had been invented in Salem, Massachusetts, around 1770 — and connected it with the old practice of tarring and feathering effigies of the Pope and the Devil at Pope’s Night festivities. Douglass Adair and John A. Schultz, eds., Peter Oliver’s Origin and Progress of the American Rebellion: A Tory View (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 1961, 94. [↩]

- On the relationship between these customs and popular politics long before the American Revolution, see David Underdown, Revel, Riot, and Rebellion: Popular Politics and Culture in England, 1602-1660 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985). [↩]

- For the Boston skimmington, see the Boston Post Boy & Advertiser, November 5, 1764; during the Boston celebration of Pope’s Day in 1764, a boy was crushed by the cart carrying an effigy of the Pope and gangs from the north and south end brawled with clubs; see the Massachusetts Gazette, November 7, 1764, and the manuscript journal of John Boyle, “A Journal of Occurrences in Boston,” ca. 1759-1778, Harvard Library, p. 43 [[November 5, 1764]: “A Child of Mr. Brown’s at the North-End run over by one of the wheels of the North-End Pope and killed on the Spot. Many others were wounded in the Evening.” [↩]

- The New-York Gazette, July 25, 1743. [↩]

- As historian Alfred Young has pointed out, reports of tarring and feathering in the late 1760s went into detail about the procedure, suggesting that the writers assumed their readers would be unfamiliar with the ritual. Alfred Young, “English Plebeian Culture and Eighteenth-Century American Radicalism,” in Margaret Jacob and James Jacob, eds., The Origins of Anglo-American Radicalism (London: Allen& Unwin, 1984), 186; for tarring and feathering in Jamaica, see The Importance of Jamaica to Great Britain Consider’d (London: Printed for A. Dodd, [ca. 1741], 19; Neil Longley York, ed., Henry Hulton and the American Revolution: An Outsider’s Inside View (Boston: The Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 2010), 121. [↩]

- William Smith to J[eremiah] Morgan, April 3, 1766, enclosed in Governor Francis Fauquier’s letter to the Board of Trade, April 7, 1766, Reese, ed., The Official Papers of Francis Fauquier, Lieutenant Governor of Virginia, 1758-1769 (3 vols., Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1980-83), 3: 1451-52. [The report was previously published in “Letters of Governor Francis Fauquier,” William and Mary Quarterly, 1st ser., vol. 21 (1913), p. 163-71. Smith’s letter to Morgan is on pp. 167-68. This version is readily accessible online.] The men who seized Smith accused him of informing on Peter Burn of the snow Vigilant. Morgan, to whom Smith reported his ordeal, was captain of His Majesty’s sloop Hornet, which cruised the lower Chesapeake and the North Carolina coast to catch smugglers. Hornet was anchored then at Norfolk when the incident occurred. Morgan forwarded the report to the governor who sent it on to the Board of Trade in London. Smith named five Norfolk merchants as his attackers. Criminal indictments were issued for those five and two others and the Board of Trade advised Fauquier to proceed against “Abettors of such Violence . . . with the utmost Severity of the Law.” They were never prosecuted. Francis Fauquier to the Board of Trade, October 8,1766, and Board of Trade to Francis Fauquier, July 22, 1766, Reese, ed., Official Papers of Francis Fauquier, 3: 1375, 1388. See also William E. White, “Charlatans, embezzlers, and murderers: Revolution comes to Virginia,” Ph.D. dissertation, College of William and Mary, 1998, 135-40. [↩]

- The Boston Chronicle, September 12, 1768; the same report appeared in The Pennsylvania Gazette on September 22, 1768; Loyalist Peter Oliver was probably alluding to this incident when he asserted that tarring and feathering was invented in Salem; see note 10 above. [↩]

- In his study of tarring and feathering Benjamin Irvin suggests (p. 201) that the practice was consciously adopted by Sons of Liberty in the late 1760s, but in the absence of documentary evidence this is speculation. See Benjamin Irvin, “Tar, Feathers, and the Enemies of American Liberties, 1768-1776,” The New England Quarterly, vol. 76 (June 2003), 197-238; The use of a tarred sheet in Salem instead of liquid tar is an intriguing difference. Tarred sheets were a rudimentary kind of waterproofing. They were used at sea, though heavier tarred canvas, called tarpaulin, was more commonly used for keep water out of hatches and provide protection to materials on deck. One of the uses of lighter tarred sheets was to wrap the dead for burial at sea. By the middle of the eighteenth century tarred sheets were also used to wrap the bodies of people who died on land from smallpox or some other pestilential disease, the idea being that it would seal up the infected body and protect the living. Wrapping the informer in Salem in a tarred sheet may have suggested that they were dead to the town. On the use of tarred sheets to wrap the bodies of victims of smallpox, see Kathleen M. Brown, Foul Bodies: Cleanliness in Early America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 129. [↩]

- The Essex Gazette, September 13, 1768. The date of this incident, September 7, is reported in the Essex Gazette account. The Boston Chronicle of September 12 did not report the date of the event involving the tarred sheet, so it is conceivable that the latter happened after September 7. The reports differ enough to make it unlikely that they were describing the same event. [↩]

- Irvin, “Tar, Feathers, and the Enemies of American Liberties,” 201, 230-31; Boston Gazette, November 6, 1769; the incident occurred on November 2; for the New Haven incident, see The Pennsylvania Gazette, October 5, 1769. For incidents in Boston on October 28, 1769, and May 18, 1770 in which informers were tarred, feathered, and carted through the streets, see Edward L. Pierce, ed., The Diary of John Rowe, a Boston Merchant, 1764-1779 (Cambridge: John Wilson and Son, 1895), 73, 75. [↩]

- Regarding Malcom’s complaints, see Thomas Hutchinson to Lord Dartmouth, January 28, 1774, Tyler, et al., eds., Correspondence of Thomas Hutchinson, 5: 424-26. The Massachusetts Gazette, January 27, 1774, reported that incident began with the boy hitting Malcom’s foot with a sled. [↩]

- John Adams described the Malcom affair in the fifth of his letters of Novanglus, published in the Boston Gazette on February 20, 1775. See Robert J. Taylor, ed., Papers of John Adams, vol. 2: December 1773-April 1775 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1977), 284-85; Three years after the affair Malcom made various charges against his former superior in Falmouth, Collector of Customs Francis Waldo, addressed to the Lords of the Treasury. Waldo answered those changes in a letter to the Lords of the Treasury dated November 21, 1776, reproducing each of Malcom’s charges and refuting them point by point. Malcom blamed Waldo for exposing him to the anger of the mob in Falmouth, which Waldo denied, pointing out that Malcom had thereafter gone “to Boston and brought upon himself a second Taring & Feathering—he has not however assigned the true Cause of this last Misfortune, which happened some time after the India Companys Teas were destroyed, & was occasioned by his beating a Boy in the Street in such a manner as to raise a Mob.” The manuscript of Waldo’s memorandum is in the British National Archives, Kew, cataloged as T1 [Treasury Board Papers and In-Letters], Subseries 525/117-120. Waldo’s memorandum is reproduced in full in Hersey, “Tar and Feathers: The Adventures of Captain John Malcom,” 440-44. [↩]

- The Massachusetts Spy reported on January 27, 1774, that Malcom threatened the boy rather than struck him and that Malcom struck Hewes with his cane. The Massachusetts Gazette of that date reported that Malcom pursued the boy while threatening him. [↩]

- Massachusetts Spy, January 27, 1774; Hewes’ account of his encounter with Malcom, his subsequent treatment by Dr. Joseph Warren, including Warren’s comment about Hewes’ skull, and the tarring and feathering of Malcom is in [Benjamin Bussey Thatcher], Traits of the Tea Party; Being a Memoir of George R.T. Hewes, one of the last of its survivors; with a history of that transaction; reminiscences of the massacre, and the siege, and other stories of old times (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1835), 126-34. Hewes’ account of the tarring and feathering of Malcom describes the path taken by the mob in detail. In his injured condition Hewes met the crowd near his brother’s house near Old South Church, where he tried to give Malcom a blanket to put over his shoulders, but was pushed away by the mob surrounding the cart. [↩]

- According to an account of the affair Gov. Thomas Hutchinson sent to the Lord Dartmouth, the constable was unable to find Malcom. See Thomas Hutchinson to Lord Dartmouth, January 28, 1774, Tyler, et al., eds., Correspondence of Thomas Hutchinson, 5: 424-26. The account in the Massachusetts Spy, January 27, 1774, contradicts this, asserting that the constable “found the doors shut against him, and was told by him, from a window, that he would not be taken that day, as he should be followed by a damned mob, but would surrender to-morrow afternoon.” [↩]

- The contemporary evidence of Malcom’s ordeal is found in Malcom’s memorial to the Massachusetts General Court dated January 30 in which he described the event, contemporary newspaper accounts, and the correspondence of contemporaries, none of whom participated in the event. Except for Malcom’s own account, these reports all seem to be second hand. Malcom’s memorial is published in Hersey, “Tar and Feathers: The Adventures of John Malcom,” 446-47. George Hewes’ account, published in 1835 in Traits of the Tea Party, adds details not found in other accounts but is otherwise consistent with them. Despite being published sixty-one years after the event, it seems generally reliable. [↩]

- Massachusetts Spy, January 27, 1774. Malcom’s role in the Regulator conflict in North Carolina seems to have been widely known in Boston and was mentioned in several accounts of the events of January 25. See, e.g., Ann Hulton to Mary Ewing Lightbody [Mrs. Adam Lightbody], January 31, 1774, [Ann Hulton], Letters of a Lady Loyalist: Being the Letters of Ann Hulton, sister of Henry Hulton, Commissioner of Customs at Boston, 1767-1776 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1927), 69-72. Mrs. Hulton noted that Malcom had been “with Govr Tryon in the Battle with the Regulators & the Governor has declared that he was of great servise to him in that Affair.” [↩]

- See Pierce, ed., Diary of John Rowe [January 25, 1769], 82, for one account. Rowe heard the “great noise and huzzaing” but did not witness the whole affair. Like other contemporary accounts, his is limited and largely second hand. No active participant in tarring and feathering Malcom left an account of the event. [↩]

- Ann Hulton to Mary Ewing Lightbody [Mrs. Adam Lightbody], January 31, 1774, Letters of a Lady Loyalist, 69-72. Hulton’s account is sympathetic to Malcom. The report that he was forced to drink hot tea until he vomited was in an October 8 dispatch from London published in the Boston Evening-Post on December 5, 1774 (and reprinted in the Massachusetts Gazette and the Massachusetts Spy on December 8). The dispatch attributed this detail to “a Gentleman lately arrived from Philadelphia.” Malcom made no mention of being forced to drink tea in his memorial of January 30. [↩]

- Pierce, ed., Diary of John Rowe [January 25, 1769], 82. [↩]

- Boston Evening-Post, January 31, 1774; The Essex Gazette, February 1, 1774. [↩]

- On the murder of Christopher Seider, see Jack Warren, Freedom: The Enduring Importance of the American Revolution (Essex, Connecticut: Lyons Press, 2023), 75-77. [↩]

- Pierce, ed., Diary of John Rowe [January 26, 1774], 82. Richardson had left Boston and was employed in the customs service in Philadelphia. A rumor had gone around that he was back in Boston. Thomas Hutchinson explained the incident to Lord Dartmouth: “The next Night there was an Attempt made to raise another Mob to search for Ebenezer Richardson, lately found guilty for Murder, but Judgment being suspended, His Majesty’s Pardon was applied for & obtained. He is now in some very inferior Employment in the Service of the Customs in Pensilvania, and it is thought a Report of his being in Town was spread for the sake of raising a Mob.” Hutchinson to Lord Dartmouth, January 28, 1774, Tyler, et al., eds., Correspondence of Thomas Hutchinson, 5: 424-26. [↩]

- Pierce, ed., Diary of John Rowe [January 26, 1774], 82; Massachusetts Spy, January 27, 1774; Hutchinson to Lord Dartmouth, February 17, 1774, Tyler, et al., eds., Correspondence of Thomas Hutchinson, 5: 439-43. [↩]

- The commissioners lowered his pension to sixty pounds a year, leaving him with an annual income of one hundred and twenty pounds. Decision on John Malcom’s Memorial of April 13, 1782, AO 12: American Loyalist Claims, series 1, vol. 105, f. 141, British National Archives, Kew, Surrey. [↩]