In our imagination the Revolutionary War ended with the British surrender at Yorktown, Virginia, on October 19, 1781, when the British and Hessians marched out of their earthworks and passed between American and French troops flanking the road. The British army was led by General Charles O’Hara, the second in command. Charles, Lord Cornwallis, said he was indisposed and left the unpleasant task of surrendering his sword to O’Hara, who tried to give it to General Rochambeau, who gestured to O’Hara to offer Washington the sword. Washington, mindful of the dignity of his commission, directed O’Hara to offer the sword to his own second in command, Major General Benjamin Lincoln. John Trumbull captured the moment in one of his magnificent history paintings: O’Hara, on foot, tenders the sword to Lincoln while Continental Army officers on our right and French officers on our left bear witness. Everyone is wearing his best uniform. French and American flags catch the breeze.

The Revolutionary War did not really end with these choreographed formalities, but Trumbull and others engaged in post-war nation building wanted us to remember it that way. The Declaration of Independence had announced the new nation’s ambition to assume its rightful place “among the powers of the Earth.” Trumbull’s The Surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown celebrates the fulfillment of that bold ambition.

The genteel minuet of formal surrender danced at Yorktown was neither the end of the war — sporadic fighting and killing continued for more than a year — nor characteristic of the war’s final phase. The last years of the Revolutionary War were marked by incidents of extraordinary savagery. The most notorious occurred in the Carolinas, where partisan war degenerated into episodes of unrestrained violence and vindictive cruelty, but barbarism was not confined to the southern backcountry. It reached New London and Groton, Connecticut, on September 6, 1781.

II

American privateers brought an unusual number of captured British merchant vessels in to New London during the summer of 1781, including the brig Hannah, bound for New York with a cargo worth eighty thousand British pounds. General Clinton, commanding the British army occupying New York City, decided to make an example of the town. He dispatched Benedict Arnold, at the head of a force of some 1,700 British Regulars, Hessians, and loyalists loaded on twenty-four transports to destroy the Hannah and any privateering vessels caught in the harbor and burn any military supplies they found. He left the operational details to Arnold, a native of Connecticut who was intimately familiar with the place.

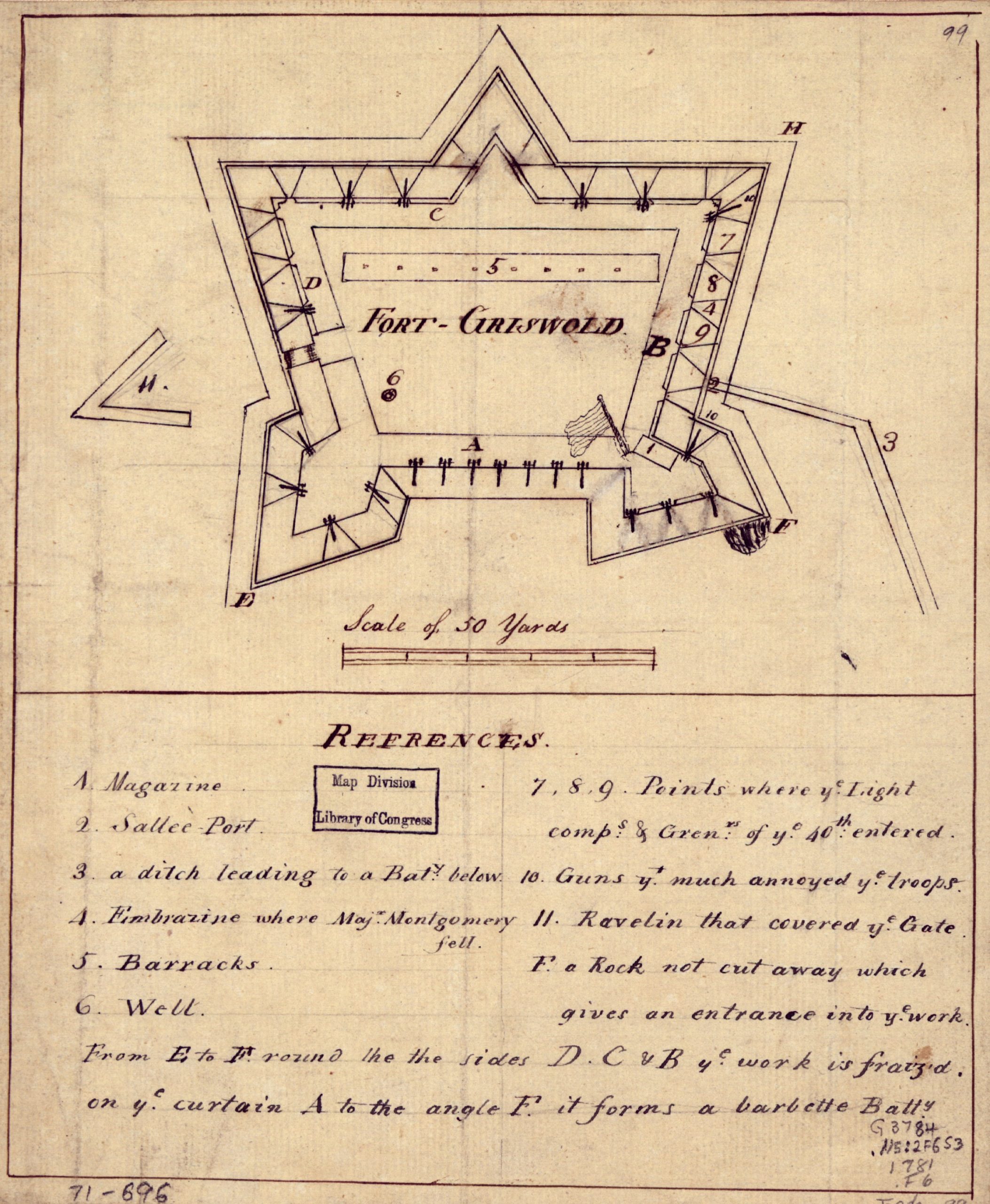

Benedict Arnold landed his troops at the mouth of the Thames River, far from the guns of Fort Trumbull and Fort Griswold, and took both forts from the land side. This map was drawn by Daniel Lyman, a loyalist officer from Connecticut who served under Arnold. Library of Congress

New London occupies the west bank of the Thames River a short distance above Long Island Sound. It was defended by Fort Trumbull — a waterside battery south of the town — and Fort Griswold, an imposing stone fort on the opposite side of the river, on a hilltop above the village of Groton. To avoid the guns of these forts Arnold came ashore at the mouth of the river and marched overland to take Fort Trumbull from the land side. He put some 850 men under Lt. Col. Edmund Eyre ashore on the east side of the river to capture Fort Griswold.1

After taking Fort Trumbull and a smaller battery, Arnold led his men through New London and ordered torch parties to burn everything of military value. They burned over 140 buildings, including docks, warehouses, shops, barns, and houses, as many as a dozen ships, and a considerable quantity of military stores. They also set fire to the church, jail, courthouse, and other public buildings.

Arnold spared almost nothing, and made no effort to restrain his men from looting and burning private homes. Gunpowder stored in one of the warehouses ignited, spreading fire through the town. Militiamen rushed toward New London from the neighboring towns in ones, twos, and small groups, but they were leaderless and disorganized and hovered ineffectively just beyond the town. They watched, powerless, as New London burned.

The troops landed on the opposite bank took longer than Arnold expected to get into position to attack Fort Griswold. They had to pick their way through marsh and thickets before climbing the heights overlooking the river. One of the reasons to take the fort was to turn its guns on any ships trying to flee upriver toward Norwich, but by the time Eyre’s detachment reached the fort Arnold had already set most of the ships ablaze. The only remaining military purpose to be served by taking the fort was to silence its guns, allowing Royal Navy vessels to sail up the river to reembark Arnold’s men along with prisoners and whatever loot Arnold decided to carry off.

By the time the British reached the fort around 150 defenders — local militia, including at least two African Americans and one Pequot Indian — had gathered inside. Some were armed only with pikes. Eyre undoubtedly expected to take the fort in short order and sent a message demanding surrender. The American commander, a militia colonel named William Ledyard, refused. When the British charged the fort, a privateer captain, Elias Halsey, fired a round of grapeshot from a heavy cannon at close range, killing and wounding dozens of attackers. The defenders repulsed the British twice with heavy losses, including Eyre and his second in command.

Fort Griswold was constructed of rough stone with earth atop the walls and surrounded by a ditch on three sides. Attackers attempting to scale the walls were exposed to cannon fire from the bastions. This British plan, probably drawn shortly after the attack, is one of the most important contemporary documents of the battle (north is to the left). The attack fell heavily on the southwest bastion of the fort, on the lower right side in this sketch. Library of Congress

On their third attempt, the British went up and over the twelve-foot walls, though they were exposed to cannon and musket fire that left dozens of dead and wounded men in the ditch below. Inside the fort, the two sides fired at close range. Fighting was briefly hand-to-hand, with bayonets and muskets turned and used as clubs. William Seymour, Ledyard’s nephew — many of the defenders were related — was shot in the knee and stabbed seven times with bayonets. Stephen Hempstead was shot through the elbow, bayoneted in the hip, and had his ribs shattered. Within minutes Ledyard could see that further resistance was hopeless and signaled to his men to surrender.2

When a British officer challenged, “Who commands this fort?” Col. Ledyard stepped forward and said, “I did, sir, but you do now,” extending the hilt of his sword in surrender.

The British officer seized the sword and ran Ledyard through, killing him. Soldiers who rushed to Ledyard’s side were cut down with bayonets. Redcoats pouring in through the open gate fired by platoons on the defenders, many of whom had thrown down their weapons when Ledyard signaled for surrender. Dozens of Americans were stabbed repeatedly with bayonets. Sixteen-year-old Peter Avery was among the survivors of the massacre, and remembered it vividly more than fifty-five years later: “the Americans were finally overcome by the superior numbers of the enemy and most inhumanely butchered by British Barbarity.” When the massacre began he fled into the barracks, where pursuing British soldiers killed three wounded men. Avery escaped into another room where he hid until the killing stopped.3

Before they were finished the British killed eighty-five Americans. Many were shot, then stabbed with bayonets. The British wounded thirty-nine Americans, many of whom died later. Arnold’s men took thirty prisoners, including wounded men, and herded them on to transports. They were confined in a sugar warehouse in New York where several more died. Other residents of New London, how many is not clear, died in their burning homes or were shot down by roving looters. As the sun went down the departing redcoats set fire to the village of Groton then boarded their transports and sailed for New York, leaving the survivors, wives and mothers, to search for their husbands and sons among the dead and dying.

With this senseless slaughter of defenseless men and boys the last battle of the Revolutionary War in the north ended — a final act of mass brutality to add to the long list of cruel and vicious acts reaching back to the spring of 1775, when redcoats shot men down on the Lexington Common. Like the defenders of Lexington the men and boys executed at Fort Griswold simply wanted to be free.

The barracks, firing platforms, and cannons are gone, but the walls of Fort Griswold are preserved in Fort Griswold State Park. The V-shaped earthwork in the foreground, called a ravelin, was designed to shelter infantry defending the gate immediately behind. After the British grenadiers and light infantry came over the far wall, they stormed the gate and fired volleys into the surrendering militia.

III

The Fort Griswold massacre was overshadowed by the victory at Yorktown. On September 5 a French fleet under Admiral de Grasse engaged a British fleet under Admiral Thomas Graves near the entrance to the Chesapeake Bay in one of the largest naval battles of the war. On September 6, as Arnold laid waste to New London and Groton, Washington’s army reached the north end of the Chesapeake Bay on its march to Yorktown. The combined American and French army invested Yorktown on September 28 and compelled the British surrender on October 19. Beyond coastal New England the tragedy at New London and Groton was little noticed. Few of the early histories of the Revolution, which focused attention on the British surrender at Yorktown, gave the tragedy more than a passing glance.

How then do we know what happened?

Memories of the tragedy persisted in southeast Connecticut, where ministers delivered annual sermons recalling the tragedy. President Monroe, a Revolutionary War veteran himself, visited the fort in 1817 and met survivors of the massacre. Stirred to action, local citizens founded the Groton Monument Association in 1820 to build a memorial to the heroes and victims of Fort Griswold. With funding from a state lottery they broke ground on September 6, 1826. The monument — an obelisk of local granite with an internal staircase and topped with a viewing platform — was built adjacent to the remains of the fort and stood 127 feet high. The association dedicated it in 1830, long before the more famous obelisk commemorating the Battle of Bunker Hill was completed.

The Fort Griswold Monument, built a few yards north of the fort, is one of the oldest Revolutionary War monuments in the country. The original observation platform at the top was replaced with a pyramid in 1881 (the addition is evident in the darker stone near the top). The plaque above the door memorializes the defenders of the fort who fell “when the British under the command of the traitor, Benedict Arnold, burn the towns of New London and Groton, and spread desolation and woe throughout this region.”

Gradually survivors and witnesses wrote down what they remembered. Stephen Hempstead, then living in St. Louis, wrote the first published account of the tragedy by a participant. “Never was a post more bravely defended,” he wrote, “nor a garrison more barbarously butchered.” Hempstead’s narrative is the source for the dramatic exchange between Colonel Ledyard and a British officer in which that officer killed Ledyard with his own sword. Some writers have expressed doubts about the veracity of Hempstead’s account, which he wrote forty-five years after the event, but we can be confident Hempstead did not make up the assertion that a British officer killed Ledyard with his own sword. Connecticut Gov. Jonathan Trumbull reported the circumstances of Ledyard’s death to George Washington a week after the massacre, writing that “Col. Ledyard perceiving the Enemy had gained Possession of some Part of the Fort & opened the Gate, although he had only three of his Men killed, thought proper to surrender Himself with the Garrison Prisoners and accordingly presented his Sword to a British Officer on the Parade who received the same & immediately thrust it through that brave but unfortunate Commander, whereupon the Soldiery also pierced his Body in many Places with Bayonets & proceeded to massacre upwards of 70 of the Officers & Garrison.”4

The Missouri Republican published Hempstead’s account in early 1826 and republished as a broadside: The following narrative of the battle of Fort Griswold, on Groton Heights, on the 6th of September, 1781, was communicated to the Missouri Republican. Jonathan Sizer, a New London printer, issued a broadside version of Hempstead’s narrative in 1840.5 Other accounts of the massacre by survivors accumulated in the files of the Pension Office in the years after Congress passed the Pension Act of 1832, authorizing modest pensions for surviving Revolutionary War veterans, including men who had served in the militia.

Hempstead’s pioneering effort was followed in 1840 by the Narrative of Jonathan Rathbun, with accurate accounts of the capture of Groton Fort, the massacre that followed, and the sacking and burning of New London, September 6, 1781, by the British Forces under the command of the traitor Benedict Arnold, By Rufus Avery and Stephen Hempstead, Eye witnesses of the same. Rathbun had been a sixteen-year-old militiaman from Colchester when he answered the alarm on September 6. Arnold was gone when the Colchester militia arrived at the burning remains of the town, which Rathbun described as “a scene of suffering and horror which surpasses description.” He assisted in burying the dead.6

The next substantial work on the massacre was compiled by William W. Harris, The Battle of Groton Heights: a collection of narratives, official reports, records, &c., of the storming of Fort Griswold, and the burning of New London by British troops, under the command of Brig. Gen. Benedict Arnold, on the sixth of September, 1781, published privately in New London in 1870 and limited to only one hundred copies.7

Charles Allyn, who owned a bookstore and small publishing operation in New London, issued what he described as a new edition “revised and enlarged, with additional notes” of The Battle of Groton Heights in 1882. Though published under the same title it should be understood as a separate and much more substantial work. Allyn included contemporary newspaper accounts, a revised version of Rufus Avery’s narrative based on Avery’s manuscript, with which Rathbun had taken liberties, Stephen Hempstead’s account, the narrative of John Hempsted (preserving his irregular spelling, which hints of the plain speech of his time), and previously unpublished accounts by participants and witnesses Thomas Hertell, Jonathan Brooks, Avery Downer, and George Middleton. Allyn also included Arnold’s report to Clinton, September 8, 1781, and dozens of official documents.8

Allyn’s Battle of Groton Heights is the foundation for subsequent work but by the time it was published the conventional narrative of the Revolutionary War was well established. Writers continued to treat the tragedy at Fort Griswold as a minor affair, worthy of attention mostly because it was the final act in the sordid career of Benedict Arnold. Indeed the episode had no apparent influence on the outcome of the war, which was decided by events far from the southern New England. But the massacre reflected what the war had become — a brutal conflict fueled by growing hatred and stoked by years of violence. Much of the fighting in the war’s final phase — in Georgia, the Carolina backcountry, upstate New York, and on the western frontiers — served no strategic purpose. The tragedy of Fort Griswold was exceptional only in is sudden ferocity.

IV

The surviving records document, in grim detail, the massacre at Fort Griswold, but they convey little of the deep sadness it left behind. To recover emotional and spiritual lives historians often turn to diaries and letters, but the plain people of Groton and New London left behind few of either.

Most of the victims of the Fort Griswold massacre were residents of Groton. They attended the same churches, worked together, and were united in the cause of independence. When they died their families drew strength from a common culture in which faith, duty, loyalty, and honor were valued above the transitory pleasures of life. They were confident that God would redeem the just and punish the wicked — sentiments they recorded on the gravestones of dozens of men, young and old, slain at Fort Griswold. In the absence of more conventional documents these gravestones provide a sense of how many ordinary people remembered the grim end of the Revolutionary War.9

Adam Shapley was wounded at Fort Griswold and died five months later. The inscription at the bottom of his gravestone reads: “Shapley thy deed reverse the Common doom/and make thy name/immortal in a tomb.”

The simplest record that the victims, like Wait Lester, age 21, “fell in the battle at Fort Griswould.” Hubbard Burrows, 41, was “killed in Fort Griswold,” and Youngs Ledyard, 30, “mortally wounded making heroic exertions for the defense of Fort Griswold.” Some of these simple inscriptions reflect the bitterness of survivors, like that of Andrew Billing, 21, “who was Inhumanely Massacred by British troops in Fort Griswold,” and Jonathan Fox, 29, who “lost his life in defense of his Country Sept 6 1781 by a wounded Received in the breast when Couragiously faceing his Un Natural Enemies.”

The gravestones document the murder of young and old alike. The British made widows of at least forty women and took the sons and fathers of others. Charles and Temparence Williams erected a gravestone to the memory of their son Daniel, 14, “who fell in the Action in Fort Griswould on Groton hill.” Deacon Joseph Allyn and his wife, Mary, buried their son Belton, 16, beneath a gravestone condemning his killer and praying for their son’s salvation:

By Cruel rage of British Man

this Body brought to dust again

But we through faith do hope this dust

Will rise in triumph with the Just.

James Comstock, at 75, was the oldest victim. His grandson Robert Comstock erected his gravestone, calling him “A signal example of valor Patriotism and heroic virtue.”

Some of the wounded men suffered for months before they died. Adam Shapley, 42, lived until February 14, 1782, then was buried beneath a stone that records that he “bravely gave his Life for his Country a fatal wound at Fort Griswold Sept 6th 1781 caused his Death.” The gravestone of Eldredge Chester, 23, records that he languished until the end of the year:

Relentless was my foe

Deaths weapons through me went,

Fell by the Fatal blow,

Lingerd till life was spent.

The gravestone of his brother Daniel Chester, 26, “Who was Killed in fort Griswould after he Surrenderd” reminds survivors:

I for my Countrys Cause have fought,

My blood was spilt on the Earth,

By Relentless Inhuman foes,

I fall a sacrifice to Death.

Several others, like the gravestone of John Lewis, 40, memorialize sacrificial death “in freedom’s cause.” They pay tribute to Peter Richards, 27, “who was willing to Hazard every danger, in defense of American Independance,” and several members of the Avery family: Daniel Avery, 40, who “nobly sacrificed his Life in Defense of fort Griswould” — David Avery, 53, who Nobly risk’d his life in defense of Fort Griswold & American Freedom; and fell a victim to british Inhumanity” — Jasper Avery, 37, “slain in fort Griswould in defense of his Country’s freedom”— Elijah Avery, 47, “having filled up Private and social life, with endearing expressions of Tenderness & affection Displayed a most brave & heroic spirit In defense of Fort Griswold And American Liberty, fell a sacrifice to british Barbarity” — and Ebenezer Avery, 48, “who fell Gloriously in Defence of fort Griswold and American Freedom . . . Exhibiting a noble Speciman of Military Valour and Patriotic Virtue.”10

Survivors carried the wounded and dying to Ebenezer Avery’s house. “Here we had not long remained.” Stephen Hempstead recalled, “before a marauding party set fire to every room, evidently intended to burn us up with the house.” The wounded men put the fires out and spent “a night of distress and anguish . . . thirty-five of us were lying on the bare floor, stiff, mangled, and wounded in every manner, exhausted with pain, fatigue, and loss of blood.”11 Ebenezer Avery was among the dead. His home is now a museum in Fort Griswold State Park. Photo © William Chervak

Many years passed before some of the gravestones were erected, testifying to long memories and enduring anger at the British. An enemy bayonet shattered 40-year-old Parke Avery’s forehead and gouged out one of his eyes. Somehow he recovered and lived another forty years, his face sunken and scarred, a reminder to all he knew of their community’s ordeal.12 His gravestone records that he “was severely wounded in Fort Griswold.” He was buried near his son Thomas, who died at 17 fighting beside his father. His gravestone says he “made his Exit in Fort Griswold” . . . Life how short: Eternity how long.”

Many of the gravestones condemn Benedict Arnold, who grew up in nearby Norwich and was connected by blood to New London families. The shared gravestone of brothers Enoch and Daniel Stanton, 35 and 25, records that they “fell with many of their friends, Sept 6, 1781, while manfully fighting for the Liberty of their Country, in defense of Fort Griswold. The Assailants were troops commanded by that most despicable parricide, Benedict Arnold.” Others, like the gravestone of John Lester, 41, refer to “Arnolds murdering corps.”

The gravestone of Christopher Woodbridge, 26, says simply that he was “kild on Fort Griswould,” but that of his brother Henry Woodbridge, 30, “slain in Fort Griswold,” calls for divine vengeance:

Will not a day of Reck’ning Come,

Does not my Blood for Vengeance Cry,

How will those wretches bear their Doom,

Who hast me slain most murderously.

The gravestones of Perkins brothers all invoke divine retribution. The gravestone of Luke Perkins, 28, is inscribed:

Ye sons of Liberty be not Dismayd

That I have fell a Sacrifice to Death,

But oh to think how will thir debt be paid

Who murtherd me when they are calld from earth.

The gravestone of his brother Asa, 32, warns his killers that “Judgment must come and you will be Rewarded for your Cruelty.” While the nearby gravestone of their brother Elisha, 37, “who fell a Sacrifice for his Countrys Cause in that horrible massacree at fort Griswould,” interprets the murders as a sign of Britain’s moral degeneracy:

Kingdoms and States Degenerate

Keep grace for ever nigh

my blood hath stain’d the british fame

for their inhumanity.

Most poignant is the gravestone of their father, Elnathan Perkins, “who was Slain at Four Griswould Septr 6th 1781 in the 64th Year of his Age.” It bears this inscription:

Ye British Power that boast aloud

of your Great Lenity

Behold my fate when at your feet

I and three Sons must Die.

A fourth son, Obadiah, 40, suffered three bayonet wounds in the massacre. When the killing stopped the British took him prisoner. They loaded him along with other wounded Americans in an empty ammunition wagon which broke loose, careened down the steep hill toward the river, and overturned when it hit a tree. Obadiah’s wife found him the next morning among the dead and dying. He recovered and lived for more than thirty years, never forgetting the sacrifice made by his father and brothers.13

We forget too easily. We should remember the cost of freedom in lives lost and families shattered. Our national identity was shaped by suffering, sadness, and pain as much as triumph. “Never for a moment,” Stephen Hempstead concluded, “have I regretted the share I had in it. I would, for an equal degree of honor, and the prosperity which has resulted to my country from the Revolution, be willing, if possible, to suffer it again.”

Victims and survivors of the Fort Griswold massacre lie in the Ancient Burial Ground in New London. The Fort Griswold Monument is visible across the Thames.

Notes

- Arnold’s expedition is summarized in standard military histories of the Revolutionary War; see, e.g., Christopher Ward, The War of the Revolution (2 vols., New York: The Macmillan Company, 1952), 2: 626-28, and is generally presented in greater detail in biographies of Arnold; a useful approach setting the expedition in the context of Arnold’s connection to the region is found in Eric D. Lehman, Homegrown Terror: Benedict Arnold and the Burning of New London (Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 2014). I am indebted to the late Jay Wayne Jackson for pointing me toward the importance of the Fort Grisworld tragedy. [↩]

- Henry Seymour to Lemuel Whitman, March 6, 1824, Pension File of William Seymour, S. 20,951, p. 30; on the wounding of Stephen Hempstead: Affidavit of Dr. Bernard Gaines Farrar [Sr.], St. Louis, Missouri, June 11, 1828, Pension File of Stephen Hempstead, S. 24,612, p. 9, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, Record Group 15: Records of the Veterans Administration, National Archives. [↩]

- Pension Declaration of Peter Avery, January 8, 1837, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, Record Group 15: Records of the Veterans Administration, National Archives. [↩]

- Stephen Hempstead’s Narrative in William W. Harris, The Battle of Groton Heights . . . Revised and Enlarged with Additional Notes, By Charles Allyn (New London: Charles Allyn, 1882), 52; Jonathan Trumbull to George Washington, September 13, 1781, George Washington Papers, Library of Congress. We do not know how Trumbull learned about Ledyard’s final moments but it was not from Stephen Hempstead, who lay critically injured. Eric Lehman describes Hempstead’s account of the brief dialogue between Ledyard and his killer as an “invention,” and a “legend” but offers no reason for rejecting it. Like other writers, he accepts other details in Hampstead’s narrative with no apparent skepticism. (Lehman, Homegrown Terror, 167 and 244, note 18). [↩]

- St. Louis Missouri Republican, February 23 (page 1, column 1) and March 2, 1826 (page 3, column 3). It was reprinted in the Jackson, Missouri, Independent Patriot, May 13, 1826 (page 1, column 3), and published as a broadside titled The following narrative of the battle of Fort Griswold, on Groton Heights, on the 6th of September, 1781, was communicated to the Missouri Republican [St. Louis, Missouri, 1826]. [↩]

- [Jonathan Rathbun], Narrative of Jonathan Rathbun, with accurate accounts of the capture of Groton Fort, the massacre that followed, and the sacking and burning of New London, September 6, 1781, by the British Forces under the command of the traitor Benedict Arnold, By Rufus Avery and Stephen Hempstead, Eye witnesses of the same. Together with an interesting appendix ([New London?]: s.n., 1840). [↩]

- William W. Harris, The Battle of Groton Heights: a collection of narratives, official reports, records, &c., of the storming of Fort Griswold, and the burning of New London by British troops, under the command of Brig. Gen. Benedict Arnold, on the sixth of September, 1781 (New London: privately printed, 1870). [↩]

- William W. Harris, The Battle of Groton Heights . . . Revised and Enlarged with Additional Notes, By Charles Allyn (New London: Charles Allyn, 1882). [↩]

- Frances Manwaring Caulkins (1795-1869), an early New London antiquarian and historian of considerable skill and diligence, transcribed the epitaphs on the gravestones of victims of the Fort Griswold massacre. More than thirty years after her death the compilation was edited by Emily S. Gilman and published as The Stone Records of Groton (Norwich: The Free Press Academy, 1903). Due to the deterioration of the stones some of the epitaphs are no longer legible. Read The Stone Records of Groton online. [↩]

- The stone now marking the grave of Elijah Avery appears to be a replacement, though executed in an eighteenth-century style topped by a winged soul. The current stone reads “In memory of Capt. Elijah Avery Who sacrificed his life in defense of Fort Griswold and American Liberty Sept. 6, 1781 in his 48th year.” [↩]

- Stephen Hempstead’s Narrative in Allyn, ed., The Battle of Groton Heights, 54-56. [↩]

- Homer D. Sweet, The Averys of Groton (Syracuse, N.Y.: The Rice Taylor Printing Company, 1894), 57-59. [↩]

- His wife, Emblem Hood Perkins (1743-1831), lived to tell this story to her granddaughter, Mary Perkins Blair, whose daughter Jennie recorded it in a memorial volume dedicated to her mother [Jennie J.B. Goodwin], In Memoriam of Mary Perkins Blair Bell and Smith, 1818-1894 ([Minneapolis, Minn.]: privately printed, [1899]), 75-77. [↩]

![Nicholas Starr Gravestone [Fort Griswold] detail 3-2 The gravestone of Nicholas Starr is one of many memorializing the victims of the Fort Griswold massacre.](https://americanideal.org/wp-content/uploads/Nicholas-Starr-Gravestone-Fort-Griswold-detail-3-2.jpg)