In the spring of 1792, George Washington received a letter from Sir Isaac Heard, an English genealogist who bore the impressive title of Garter King of Arms. Sir Isaac was one of the official genealogists to the English aristocracy. He had encountered a document related to the Washington family and this had prompted him to trace President Washington’s English lineage — just as he was responsible for tracing and verifying the lineages of the British nobility. After all, wasn’t the new American president a kind of elected monarch?1

Heard had learned a great deal about the people he supposed were Washington’s English ancestors, but he knew almost nothing about the American Washingtons. The document he encountered — which he accurately suspected was a copy of the will of George Washington’s paternal grandfather, Lawrence Washington — provided him with the information to make a simple sketch of George Washington’s Virginia progenitors, which he enclosed, along with a small painting of the Washington arms, of which he seems to have imagined George Washington was unaware. He asked President Washington to supply the missing details in his chart.

The truth was that George Washington did not know a great deal about the history of his family, and most of what he did know was vague and indistinct. His father, Augustine, had died when George was eleven. George’s grandfather, Lawrence Washington, had died when Augustine was a small boy. These early deaths seem to have erased much of the family’s memory of its past. President Washington was largely cut off from his family’s history. He knew the names of his father, paternal grandfather Lawrence Washington, and paternal great-grandfather, John Washington, the immigrant who had arrived in Virginia on the Sea Horse of London in the mid-seventeenth century. But he knew little else.

What’s more, Washington was apparently a little uneasy about Heard’s inquiry. He had never given his ancestry a great deal of thought. He used the Washington family crest on some of his silver and the seal he used on his correspondence, and the family arms on his bookplate and the sides of one of his coaches, but he was uncertain whether family lineage was an appropriate concern for the president of a revolutionary republic that was in the process of abandoning principles and practices inherited from centuries of monarchical culture.

Washington nonetheless responded to Heard’s inquiry and spent the remaining years of his life, off and on, collecting genealogical information for his new English correspondent. Washington’s curious ambivalence about the whole process — his expressions of disdain mixed with his evident curiosity about his family history — reflected the politically-charged meaning genealogy had in the late eighteenth century. It also reflected Washington’s conception of his role as a republican chief executive and his uncertainty about the importance of family background and inherited tradition in the new American republic.

II

George Washington knew that as the first chief executive of the United States he was setting precedents that would shape the course of the American republic for generations. “Many things which appear of little importance of themselves and at the beginning,” he wrote in May 1789, “may have great and durable consequences from their having been established at the commencement of a new general Government.” He added wisely that it would be easier to begin with “a well adjusted system . . . than to correct errors or alter inconveniences after they shall have been confirmed by habit.” The “eyes of America” he wrote to his friend David Stuart, “perhaps of the world — are turned to this Government; and many are watching the movements of all those who are concerned in its administration.”2

President Washington was justifiably self-conscious about his new role. Americans of the revolutionary generation — and most of all Antifederalist critics of the Federal Constitution — were especially suspicious of presidential power. The revolutionary movement had been fueled by real and perceived abuses of executive authority — by customs officials, tax collectors, colonial governors, and the distant colonial bureaucracy in London. In creating their own governments the revolutionaries had gone to great lengths to prevent the abuse of executive power — vesting executive authority in committees rather than individuals, limiting the time individuals could hold executive offices, banning individuals from holding more than one office at a time, and by shifting executive authority to state and local governments, where alert citizens could keep watch over officials for signs of corruption. The government established by the Articles of Confederation had no independent executive branch at all.

The convention that framed the Federal Constitution agreed that the establishment of a more effective executive branch was essential for the preservation of the Union, but it members were not immune to ideological anxiety about the abuse of executive power — and perhaps most of all, about creating a chief executive who would behave as an elective monarch. They considered vesting executive authority in a committee, and once the decision was made to have a single executive, they debated the powers of the office at length before agreeing to invest a single president with the entire executive authority of the federal government. The convention only took this step because, as one of the delegates wrote, “many of the members cast their eyes towards General Washington as President; and shaped their Ideas of the Powers to be given to a President, by their opinions of his Virtue.” Despite the faith that Americans had in Washington, suspicion of the energetic use of executive authority persisted under the Federal Constitution. “The doctrine of energy in Government,” John Page declared on the floor of First Congress, “is the true doctrine of tyrants.”3

George Washington did not share this ideological preoccupation about the corrupting influence of executive power. He believed that executive authority, properly checked but concentrated in the hands of relatively few, was essential to effective government. But he understood that the presidency was on trial, and that every measure of his administration would be scrutinized closely.

Supporters wore “Long Live the President” buttons like this one to celebrate Washington’s inauguration. They imagined Washington was a kind of elected king who would be reelected every four years for as long as he lived. Washington insisted he was a public servant, not a king. Courtesy Stacks Bowers Gallery

Among Washington’s most important accomplishments as president was restoring American confidence in strong executive leadership. Washington endowed the presidency with the dignity requisite for a head of state, while avoiding the ostentation associated with monarchy. He administered the government with fairness, efficiency, and integrity, assuring Americans that the president could exercise extensive executive authority without partiality, caprice, or corruption, and he executed the laws with justice and restraint, establishing precedents for broad-ranging presidential authority, while convincing his countrymen that the energetic government need not become tyrannical.

But despite his caution — all his circumspection — Washington could not avoid charges that he was imitating the forms and practices of monarchy. In the days after his inauguration, the press of invitations and the crowds of visitors seeking Washington’s attention threatened to make it impossible for him to administer the government at all. He quickly concluded that he would have to establish formal procedures regulating his social life in order to have any time left to manage the government. After consulting with John Adams, John Jay, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton, Washington decided to hold weekly levees at which to receive casual visitors. He also decided not to return visits or accept private dinner invitations.

A few critics — more as the administration progressed — charged that these policies imitated the forms of monarchy. The levees came in for much of the criticism. They were stiff, ceremonial affairs, at which callers were presented to the president and formed a circle around the room, after which Washington made his way around the circle and spoke briefly to as many of his visitors as he could. Any respectably dressed man could attend one of these events. Neither invitations nor letters of introduction were required. When he learned that prominent Virginians, including his neighbor George Mason, were saying that the levees were part of a conspiracy to surround the president with the pomp of royalty, Washington privately complained that he could not see “what pomp there is in all this.” Perhaps, he mused sarcastically, “it consists in not sitting.”4

Such criticism frustrated Washington. He generally disliked being the object of public rituals and avoided them whenever he could. He privately insisted that he would rather “be at Mount Vernon with a friend or two about me than to be attended at the seat of government by the officers of state and the representatives of every power in Europe.” He disapproved of proposals to invest the president with aristocratic-sounding titles like “His Elective Highness.” He discouraged public celebration of his birthday, partly because such celebrations interfered with the public business and partly because they were an imitation of the British custom of celebrating royal birthdays.5

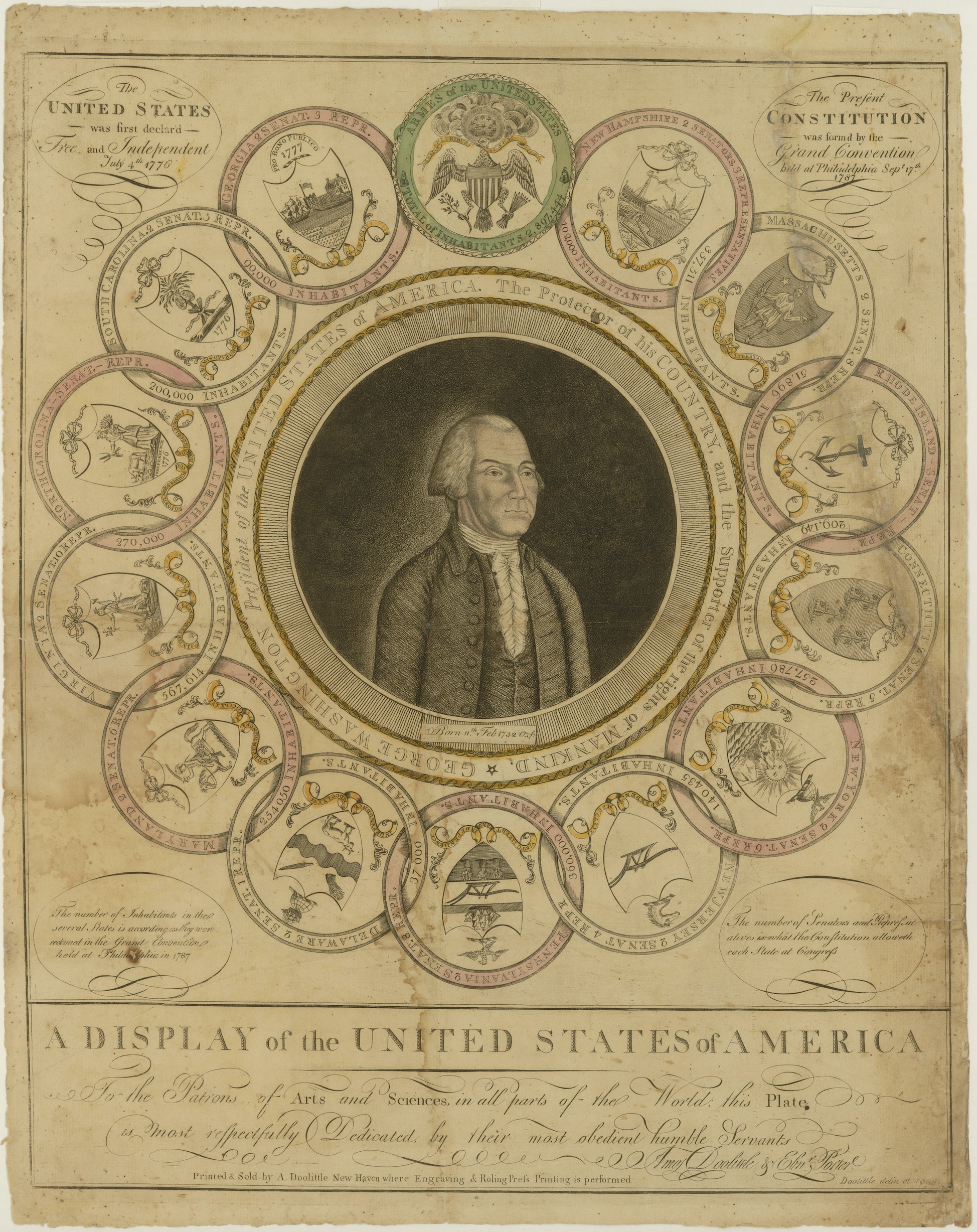

In A Display of the United States of America, published shortly after Washington’s inauguration, Amos Doolittle imitated monarchical traditions by describing Washington as “The Protector of his Country, and the supporter of the rights of Mankind” but portrayed the new president in a simple black suit, in sharp contrast to the ermine and silk worn by kings. John Carter Brown Library

His wishes in this last respect were invariably ignored. The elaborate birthday balls and fireworks each year gave critics fresh opportunities to charge that the men around Washington — if not the president himself — were straining to make him into an American king. Everyone agreed that he looked and carried himself like a monarch. Although Washington wanted to get out of the presidency as quickly as possible (and actually considered resigning as early as 1790, one year after taking office) it was widely expected that he would be president for life. Opponents of the new government expressed their relief that Washington had no son to succeed him as America’s elective monarch.

III

It was in this period of anxiety about the character of the new government that Washington received Sir Isaac’s first letter in the spring of 1792. Washington had no evidence regarding Heard’s motives in wanting to perfect his genealogy of the Washington family. Nor do we. Perhaps it was simply professional curiosity.

More likely, Heard wanted to be able to describe with precision the relationship of his English clientele to the new American president. By the end of the American Revolution, Washington’s fame was international. Members of the English nobility — particularly Whigs, who regarded the government of Lord North with disdain and who embraced the fashionable cause of American liberty — were pleased to claim a connection to Washington, who seemed to embody the virtues celebrated in the greatest heroes of classical antiquity. Some of them, like the Scottish lord, David Erskine, eleventh earl of Buchan, began to write to Washington, proudly calling themselves his “kinsman.” Buchan exchanged at least eighteen letters with Washington between 1790 and 1798, and presented the president with a box made from wood taken from a tree said to have sheltered the Scottish rebel William Wallace after the battle of Falkirk. Men like the earl wanted to know precisely how they were related to Washington, and Heard probably aimed to satisfy them.6

Sir Isaac Heard wears the badge of the Garter King of Arms in this 1817 engraving by Charles Turner after a portrait by Arthur William Devis. As a young man Heard served in the Royal Navy and married a widow from Boston. He served as Garter King of Arms from 1784 to 1822. National Portrait Gallery, London

Heard’s letters were directed to the president privately. Washington undoubtedly understood that by indulging the Englishman he would not — at least immediately — expose himself to the charge that he was trying to buttress a claim to an American crown by tracing his lineage to some distant member of English nobility or even to a member of a royal family. Yet Washington realized that Heard’s project might be regarded as antithetical to republican principles. In 1783 Washington had welcomed the establishment of the Society of the Cincinnati — an organization composed of former Continental Army officers, in which membership was to be hereditary — and was shocked by the outcry against the group. Samuel Adams complained that the organization represented “as rapid a Stride towards an hereditary Military Nobility as was ever made in so short a Time.” The ferocious response to the Society forced Washington and many of his peers to reconsider the idea of hereditary honor and illuminated the inconsistency of hereditary principles with the republican ideal of equality.7

This episode surely prepared President Washington to regard Heard’s inquiries with caution and even suspicion. Genealogy was only just beginning to emerge from its historic function as a support and symbol of the very hereditary privileges the American Revolution had sought to overturn. Though Heard’s inquiries were private, Washington had long since learned to regard all of his correspondence — particularly with strangers — as potentially public, since over the years indiscreet correspondents or political opponents had published private letters in an effort to embarrass or discredit him and many other leaders of the Revolution. “My political conduct,” Washington explained to his nephew Bushrod in another context, “must be exceedingly circumspect and proof against just criticism, for the eyes of Argus are upon me, and no slip will pass unnoticed.”8

Washington might sensibly have ignored Heard’s inquiries, but the republican misgivings he may have had about Heard’s project were overcome by Washington’s deeply ingrained gentility — the patterns of gentlemanly behavior he had imbibed as a young man, reflected in his famous “Rules of Civility,” the maxims on personal conduct Washington copied as a boy and lived by as a man. Attention to Heard’s request, Washington wrote, seemed due, “on account of his politeness” and the “earnestness” of his appeal.9

Washington’s ideological reluctance about Heard’s inquiry was also overcome by curiosity. In his initial reply to Heard, Washington feigned disinterest, explaining that genealogy was a “subject to which I confess I have paid very little attention. My time has been so much occupied in the busy and active scenes of life from an early period of it that but a small portion of it could have been devoted to researches of this nature, even if my inclination or particular circumstances should have prompted the inquiry.”10

But Washington was plainly interested. Along with being a revolutionary republican, Washington was a member of the late colonial Virginia gentry. Few social groups in American history have been as concerned with family connections. The first families of Virginia — the Lees, Carters, Byrds, Randolphs, Custises and their peers — maintained their remarkable hegemony over late colonial society through intermarriage, which extended their social and political influence into every part of the colony. The Washington family had never quite reached that level of Virginia society. The colonial Washingtons were second and third tier members of the gentry. The eldest sons might be deemed fit to marry the younger daughters of the first families — George’s eldest half-brother Lawrence, who inherited the bulk of their father’s estate, married a Fairfax — but the eldest son of a Lee or a Byrd was unlikely to marry a Washington girl.

Before the Revolution intervened and offered George Washington the prospect of a kind of secular immortality — of being remembered like a hero out of classical antiquity — his highest ambition seems to have been to elevate the Washingtons to the highest tier of the Virginia gentry. His marriage to the widow of John Parke Custis and his expansion of Mount Vernon into a great landed estate reflected this ambition. Even the radicalism of the American Revolution — though it had offered Washington a different goal — had not completely erased the interest in family ties that was characteristic of his social background. Washington’s letters to Heard reflected the ambivalence Washington felt. Even while he feigned disinterest in Heard’s research and apologized for not having the time, information, or inclination to pursue the work himself, Washington wrote that “I . . . shall be glad to be informed of the result, and of the ancient pedigree of the family.”10

Anyone who has ever undertaken to reconstruct the story of their family in later life, without the aid of living informants — parents and grandparents, aunts and uncles — can sympathize with Washington’s situation. To answer Heard’s immediate questions, Washington wrote straight away to one of his oldest living relatives — Hannah Fairfax Washington, the widow of his older distant cousin, Warner Washington — appealing for help. “As I have heretofore paid but little attention to this subject,” Washington explained, “I am induced to ask your aid, presuming, as your late Husband’s father was older than mine you might, either from your own knowledge or a recurrence to documents, or tables in your possession, be able to complete the sketch” sent by Heard.11

Hannah Washington was able to supply some but not all of the needed information. Much more was not readily available, Washington pointed out to Heard, because “We have no Office of Record in this Country in which exact genealogical documents are preserved; and very few cases, I believe, occur where a recurrence to pedigree for any considerable distance back has been found necessary to establish such points as may frequently arise in older Countries.” This was certainly true. Few Virginia land patents were as much as 150 years old, and the United States had few aristocrats whose claims to hereditary titles had to be supported by genealogical study.10

Heard gently pressed for more information, particularly about the American descendants of Lawrence, the brother of President Washington’s great grandfather. Washington knew even less about these distant cousins than he did about his own line, despite the fact that members of this branch of the family were his closest childhood companions and lifelong friends. But instead of disappointing Sir Isaac — and not satisfying his own curiosity — the president wrote to one of these old friends, Lawrence Washington of Chotank, for information.12

Lawrence Washington of Chotank was the leading member of his generation of the King George County branch of the family — known to some as the “Web-Footed Washingtons” because their plantations were laid out along marshy Chotank Creek. But like George Washington, Lawrence of Chotank’s father had died when Lawrence was a boy. He probably didn’t have much information at his disposal.

Charles Balthazar de Saint-Mémin drew this portrait of the president’s nephew William Augustine Washington in 1804. Washington had inherited the ancestral home in Westmoreland County and spent years chasing genealogical information for his uncle. Library of Congress

When no reply came back from Lawrence of Chotank, an irritated Washington wrote to his nephew William Augustine, who had inherited the plantation where Washington was born. Washington continued to pose as uninterested in Heard’s genealogical enterprise. The whole business had been dumped in his lap “without any application, intimation, or the most remote thought or expectation of the kind, on my part,” Washington explained. “I have not the least Solicitude to trace our Ancestry,” he insisted. Then, utterly contradicting himself, he asked William Augustine to document the history of the first Lawrence Washington in Virginia, even instructing William to visit the family burying ground on Bridges Creek to copy the tombstone inscriptions. Some time later Washington recorded his frustration that William Augustine had not replied as promptly as he wanted.13

In early 1798, George Washington — now the former president — was still after William Augustine for the information, though he insisted that “the enquiry is, in my opinion, of very little moment.” William Augustine replied in March 1798 describing his months of effort to comply with his uncle’s requests — his efforts to track down the genealogy of the descendants of Lawrence the Immigrant, and his examination of the tombstones, but his efforts were not good enough for the general. Washington asked him track down more information, an effort that apparently ended only with George Washington’s sudden death on December 14, 1799.14

IV

George Washington’s curious ambivalence about Sir Isaac Heard’s efforts to trace the lineage of the Washington family reflects a larger tension in the social and political thought of Washington’s generation. The American Revolution occurred at a moment when American culture was becoming more English, not less so. To an earlier generation of historians, the American Revolution was a natural consequence of the maturing of the American colonies, and the development of a distinctive American culture. But in many important ways, late eighteenth-century British America was becoming more like the mother country.

By the eve of the Revolution, the social instability of the early colonial period, with its frightful mortality and enormous social dislocation, had given way to a relatively stable society much more like that of provincial England than anything that had come before. Mortality rates were comparable to those of England. Despite their distinctiveness, colonial cities like Boston, New York, and Philadelphia were more like Bristol or Norwich than the colonial outposts of the seventeenth century. Tenancy, the dominant form of land tenure in Britain, was growing in British America. And at the lower end of the social scale, Americans were beginning to experience the kind of poverty that was endemic to the Old World.

At the upper end of the social scale, Americans were beginning to acquire a native aristocracy. A few representatives of the lesser nobility had come to the colonies in the seventeenth century, but most had quickly returned home. A few nobleman, like Washington’s early patron, Thomas, Lord Fairfax, subsequently settled in the New World. But in the mid-eighteenth century, something quite different was happening. British titles were beginning to descend to colonial Americans, including men who had never been to Great Britain. William Alexander, a wealthy New Jersey landowner, laid claimed to a Scottish earldom. His American contemporaries acknowledged him as Lord Stirling — a title he continued to use as a major general in the Continental Army and a trusted subordinate of Washington. Parliament refused to recognize his claim, but Stirling’s case illustrates the broader trend that was making Americans more British. Several perceptive members of Parliament even suggested the deliberate creation of American peers in order to bind the leading gentry of the colonies to the mother country. Though this suggestion was never acted upon, it reflected the increasing social maturity of the American colonies.

The American Revolution, asserting principles of universal equality and republican liberty, challenged the idea of hereditary privilege at the very moment it was manifesting itself in America. Washington and his contemporaries were keenly aware that the new nation, founded on republican principles, represented a break with the past and the oppressive traditions of aristocratic privilege and oligarchic control that most Americans believed were antithetical to the ideal of republican liberty. Genealogy seemed, to many revolutionary Americans, a part of the past, a tool used to justify aristocratic privilege.

Few Americans had dedicated themselves more wholeheartedly to the ideal of republican liberty than George Washington. Yet Washington — like so many Americans in the last two centuries — could not resist his desire to understand his family’s past. Like any good Virginia gentleman of his generation he wanted to understand the history of his family and its connections, but found it necessary to pretend that he wasn’t interested at all.

George Washington’s ambivalence about the history of his own family is one measure of the social and intellectual distance that separates him from us. Genealogy is no longer a tool of aristocratic privilege. Like everything else in American life, genealogy has been thoroughly democratized. Many Americans now delight in tracing their lineage to a highwayman or a horse-thief as much as to a duke or an earl. Genealogy is now an innocent pursuit that enriches our sense of family and cultural identity in a time when the bonds of everyday community have been weakened by the inexorable processes of modern economic development. Genealogists might now be fairly described as the least dangerous people in America, and genealogy as the least subversive pursuit imaginable.

But to many of the new citizens of the revolutionary American republic, used to guarding against real and imagined conspiracies to subvert their liberties and impose a home-grown aristocracy or even an American monarchy on the ruins of their freedom, anything more than a casual interest in pedigree was regarded with suspicion. Washington’s pretended lack of interest in Heard’s inquiries was a natural defense against the charge that he harbored monarchical ambitions.

Washington’s pose also reflected his generation’s uncertainty about the significance of heredity, family tradition and history itself. Washington, like nearly every American gentleman of his generation, was influenced the eighteenth-century Enlightenment — that great intellectual movement that sought to apply the insights of modern science and philosophy to solve the problems of mankind. One of the central insights of the Enlightenment — perhaps the insight at its very core — was John Locke’s assertion that all human thought was based on personal sensory experience. People, Locke held, are born blank slates, and their identity is formed by their environment and personal experiences, including their education, conversation and reading. Locke and most of the philosophers of the Enlightenment rejected the idea that an individual’s identity was, in any important sense, inherited from his ancestors.

Early modern genealogy, which often carried with it an implicit assertion that character traits — courage, honor, piety, and so forth — are passed through families along with land and titles, was thus antithetical to the mentality of the Enlightenment. Washington’s repeated expressions of disinterest in genealogy were consistent with his attachment to the general principles of Enlightenment thought — an attachment also reflected in Washington’s political ideas, religious sentiments, agricultural practices, and his developing views on slavery.

His expressions of disdain for genealogy were also consistent with his view of history. Washington shared the Enlightenment’s ambitions for the improvement of the human condition, and he rejected the idea that the new nation should be governed, in any sense, by the dead hand of the past. Washington was firmly convinced that Americans were a special people, with the prospect of greatness laid out before them, but he thought the future greatness of the United States depended upon adherence to republican principles and the energetic and wise exploitation of the vast resources of the American continent. He did not think that America’s potential was connected to the colonial past or was in any sense a fulfillment of that past. For Washington, the American Revolution represented a dramatic break with what had come before. History, except as a model for personal conduct, held little fascination for him.

In this regard, as in many others, Washington’s ideas were representative of a revolutionary generation that was rapidly fading by the time of his death. By then, many Americans — gentlemen at first, some disturbed by the radical democratization of society, but increasing numbers of ordinary people as well — were beginning to turn their attention to the richness of the American past. The establishment of new institutions — the Massachusetts Historical Society, the American Antiquarian Society, and the Historical Society of Pennsylvania among them — reflected this new engagement with American history and fueled an unexpected surge in genealogical work of all kinds during the early years of the nineteenth century.

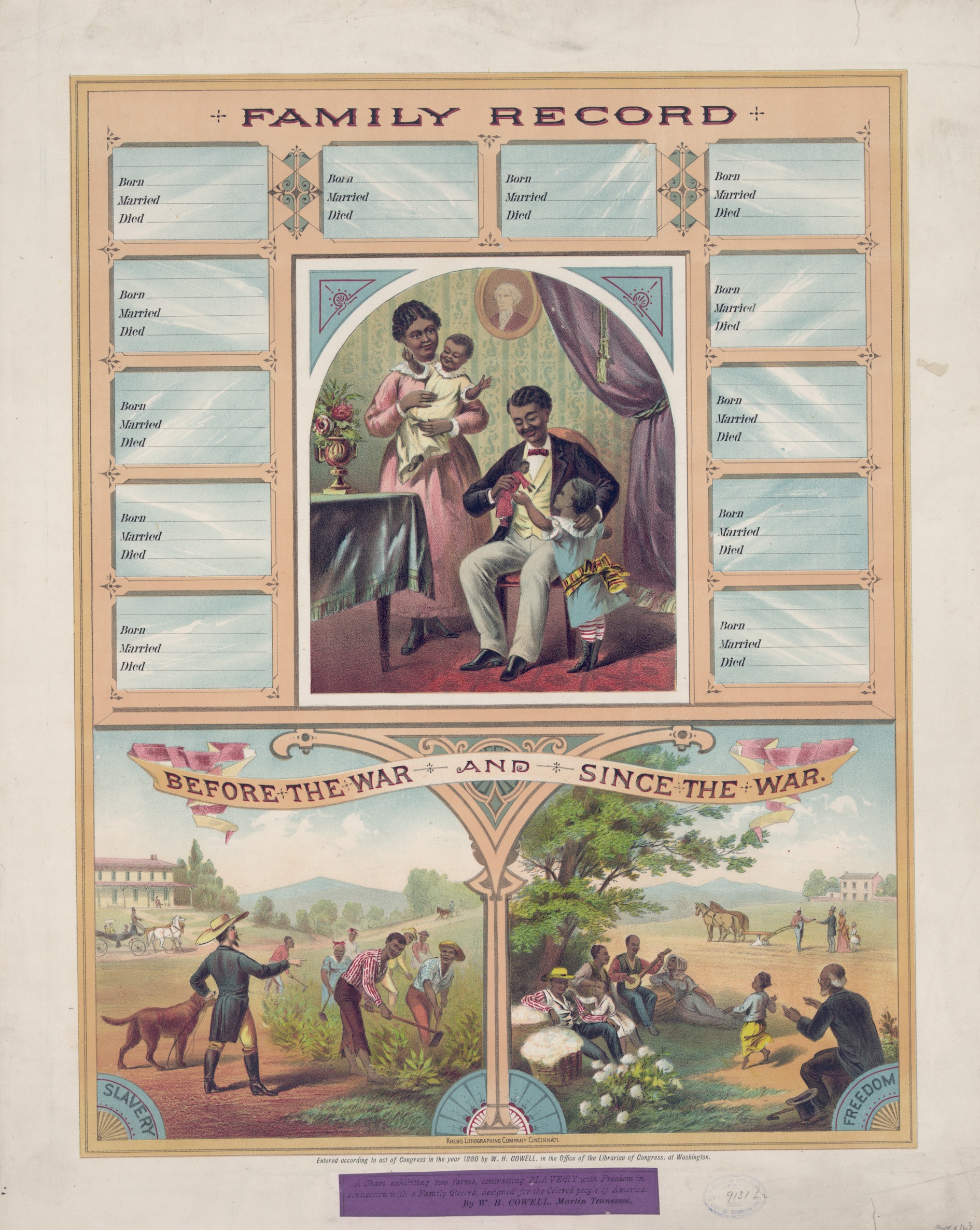

By 1880, when a Cincinnati lithography firm published this family record especially for black Americans, interest in documenting family history was no longer associated with aristocratic pretensions. It had become a part of democratic culture, accessible to all. Library of Congress

George Washington, ironically, was partly responsible for this development. By administering the executive branch of the new government with justice and restraint, he had persuaded his countrymen that they had no reason to fear that the new federal government would deprive them of their liberties or impose a new aristocracy and monarchy on the United States. By working to make fears of aristocratic oppression and monarchical conspiracies a thing of the past, Washington unwittingly helped to make genealogical study — once widely regarded as a tool of aristocratic privilege — a basic part of American historical scholarship.

Jack Warren originally presented this essay as the banquet address to the annual convention of the National Genealogical Society.

Notes

- Issac Heard to George Washington, December 7, 1791, Mark A. Mastromarino, ed., The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 9: September 23, 1791-February 29, 1792 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000), 258-60. [↩]

- George Washington to John Adams, May 10, 1789, Dorothy Twohig, ed., The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 2: April 1, 1789 -June 15, 1789 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1987), 245-50; George Washington to David Stuart, July 26, 1789, Dorothy Twohig, ed., The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 3: June 15-September 5, 1789 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1989), 321-27. [↩]

- Butler did not think it wise to rely on Washington’s successors being so dependable and completed this thought by suggesting that Washington, “by his Patriotism and Virtue, Contributed largely to the Emancipation of his Country, may be the Innocent means of its being, when He is lay’d low, oppress’d” — Pierce Butler to Weedon Butler, May 5, 1788, Max Farrand, ed., The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787 (3 vols., New Haven: Yale University Press, 1911), 3: 301-304; Joseph Gales, comp., The Debates and Proceedings of the Congress of the United States, vol. 1 (Washington: Gales and Seaton, 1834), 572 [June 18, 1789]. [↩]

- George Washington to David Stuart, June 15, 1790, Dorothy Twohig, Mark A. Mastromarino, and Jack D. Warren, eds., The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 5: January 16 -June 30, 1790 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1996), 523-28. [↩]

- George Washington to David Stuart, June 15, 1790, ibid. [↩]

- Earl of Buchan to George Washington, June 28, 1791, Mark A. Mastromarino, ed., The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 8: March 22 -September 22, 1791 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1999), 305-8. [↩]

- Samuel Adams to Elbridge Gerry, April 23, 1784, Harry Alonzo Cushing, ed., The Writings of Samuel Adams, vol. 4 (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1908), 301-303. [↩]

- George Washington to Bushrod Washington, July 27, 1789, Twohig, ed., Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series 3: 334. [↩]

- George Washington to Hannah Fairfax Washington, March 24, 1792, Robert F. Haggard and Mark A. Mastromarino, eds.,The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 10: March 1-August 15, 1792 (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2002), 152-53. [↩]

- George Washington to Isaac Heard, May 2, 1792, Haggard and Mastromarino, eds., Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series 10: 332-34. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- George Washington to Hannah Fairfax Washington, March 24, 1792, Haggard and Mastromarino, eds.,Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series 10: 152-53. [↩]

- This letter is missing, and is known only from George Washington’s reference to it in his letter to William Augustine Washington of November 14, 1796 (see note 13 below) in which he wrote that Heard “wished to know the descendents of Lawrence from whom the Chotanck Washington’s have proceeded. I wrote (to the best of my recollection) to Lawrence Washington for an account of them, but have never received one, and of course could give none.” [↩]

- George Washington to William Augustine Washington, November 14, 1796, for which see George Washington William Augustine Washington to George Washington, March 23, 1798, W. W. Abbot, ed., The Papers of George Washington, Retirement Series, vol. 2: January 2, 1798 -September 15, 1798 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1998), 151-55, note 2. [↩]

- George Washington to William Augustine Washington, February 27, 1798, Abbot, ed., Papers of George Washington, Retirement Series 2: 109-11; William Augustine Washington, obviously reluctant to disappoint his uncle, responded on March 23, 1798, with details regarding his research:

I did receive your Letter of the 14th of Novr 1796, inclosing a Copy of Sir Isaac Heards Letter to you, respecting the Genealogy of our family, at the time I recd it I was extremely ill and confined to my bed with a severe fit of the gout; however in that situation Genl Lee called to see me on his way to Philadelphia; I desired him to inform you that I had recd your Letter & that I should attend to your request; & having heard that Mr Herbert of Alexandria, had found among the papers of Colo. Carlile, (who was one of the Executors of my Uncle Lawrance Washington) a paper containing a Genealogical description of our Family from their first coming over to America, I requested of Genl Lee to apply to Mr Herbert for it, & if he could obtain it to take it on to you — as soon as I recovered I pursued my inquiries here, by examining of all my papers, the Tomb Stones at the Burial ground of our Ancestors, and could find nothing which lead to an investigation — I then wrote to Mr Lawrance, & Robt Washington of Chotanck; I got very little information from them, they said that they always understood that they were decended from Lawrence, who came over with John, our Ancestor; but Mr Robt Washington sent me word, that he understood, that Mr John Washington near Leeds, had a Genealogical Table of the Family from the first coming over of our Ancestors[.] I immediately wrote to a Mr Balmain, who married one of Mr J. Washingtons Daughters, & who had administered upon the Estate; requesting that he would examine his Testators papers & if he could find such a paper, that he would let me have it, or a Copy of it, soon after he was to see me, & informed me that he had looked over the greater part of the papers, but had not discovered such a paper, but if he should meet with it he would certainly send it to me — soon after he removed into your Neighbourhood & I have never seen or heard from him since; This information I requested Mr Bushrod Washington to give you last summer, when he went from here to Mt Vernon; I shewed him your Letter to me, & communicated my researches to him, & he promissed me that he would inform you of the results; I fear you will find some difficulty in complying fully with Sir Isaac Hear[d]s request as to Lawrance, unless you could find out where he lived & died; his will I suppose is on record; which would shew nearly about the time he died; If I can get any further information on the subject I will immediately communicate it to you.

William Augustine Washington to George Washington, March 23, 1798, Abbot, ed., Papers of George Washington, Retirement Series 2: 151-55. [↩]

![George Washington [Lansdowne Portrait], Gilbert Stuart, 1796, National Portrait Gallery Washington, 3-2 detail](https://americanideal.org/wp-content/uploads/George-Washington-Lansdowne-Portrait-Gilbert-Stuart-1796-NPG-Washington-3-2-detail-scaled.jpg)