Late on the evening of April 18, 1775, nine hundred British Regulars set out through the dark streets of Boston. They were headed for Concord, a village sixteen miles west, where spies reported the colonists had accumulated a store of arms and ammunition, including two brass field cannons smuggled out of Boston. General Gage thought the soldiers might run into trouble, so each man carried thirty-six rounds of powder and ball. The men moved quietly to avoid waking the townspeople. A dog barked as they passed. A soldier quickly killed the dog with his bayonet.

The British hoped to surprise the colonists, but that was impossible. Patriot spies had already reported the army’s plan to Joseph Warren, who dispatched Paul Revere on a ride between Boston and Concord to warn the country people that the Regulars were on the march. Thanks to Revere and the other riders, the countryside was soon filled with militiamen marching or riding through the night to join their companies. British soldiers could see them moving in the darkness. Major John Pitcairn, commanding the troops at the head of the column, ordered his men to stop and load their muskets. He did not intend to face an ambush unprepared.

Pitcairn’s men reached Lexington, about nine miles from Boston, as dawn broke on April 19. The Lexington militia—a company of about eighty men, commanded by a farmer named John Parker—was formed in a line on the Lexington Green. Parker saw that he was badly outnumbered, but he was determined to make a show of resistance to let the soldiers know that the colonists would protect their homes and property. One nervous militiaman said, “There are so few of us it is folly to stand here.” Paul Revere, who was on the scene, reported that Parker told his men “Let the troops pass by, and don’t molest them, without they begin first.”

Pitcairn ordered his leading companies off the road and into a line of battle facing the Lexington men. A British officer, probably Pitcairn, shouted to Parker and his men to lay down their weapons. Parker knew that resisting such a large British force would be useless. After a tense moment he ordered his men to disperse, but without laying down their arms. Most of the militiamen began to scatter, retreating from the Regulars or moving off to the sides in small groups. A few Americans stubbornly held their ground and glared at the British soldiers.

A moment later someone fired a shot. Most witnesses agreed that it did not come from either line. British soldiers said they saw a flash from behind a wall. Someone else said they saw a shot fired from a window of the nearby tavern. Some in the militia thought the first shot was fired by a British officer on horseback. Whoever fired first, the Regulars responded, without orders, by firing on Parker’s retreating men.

A few of the militia fought back. Jonas Parker stood his ground, his musket balls in his hat at his feet, and fired on the Regulars. He was shot down. As he struggled, wounded, to reload his musket, an advancing British soldier ran him through with a bayonet. Jonathan Harrington retreated, but was shot down in his own front yard. He crawled to his door and died there, with his wife and son watching. As the smoke cleared, eight Americans lay dead and another nine wounded.

The British officers got their men back into line and marched on. By the time they reached Concord, seven miles away, about three hundred militiamen were waiting. As the Regulars approached, the militia retreated westward. across the Old North Bridge over the narrow Concord River. They watched as the British troops occupied the town and went from house to house, looking for arms. The patriots had removed nearly all the weapons from the town. The British soldiers found a few iron cannon barrels and some musket balls, but little else.

The militia, their number grown to about five hundred, confronted the Regulars at the Old North Bridge. The militiamen marched toward the bridge and fired on the British soldiers in line on the opposite side. The Regulars retreated in confusion as the militia killed three and wounded nine, including four officers. The British commander ordered his men back on the road and headed toward Boston.

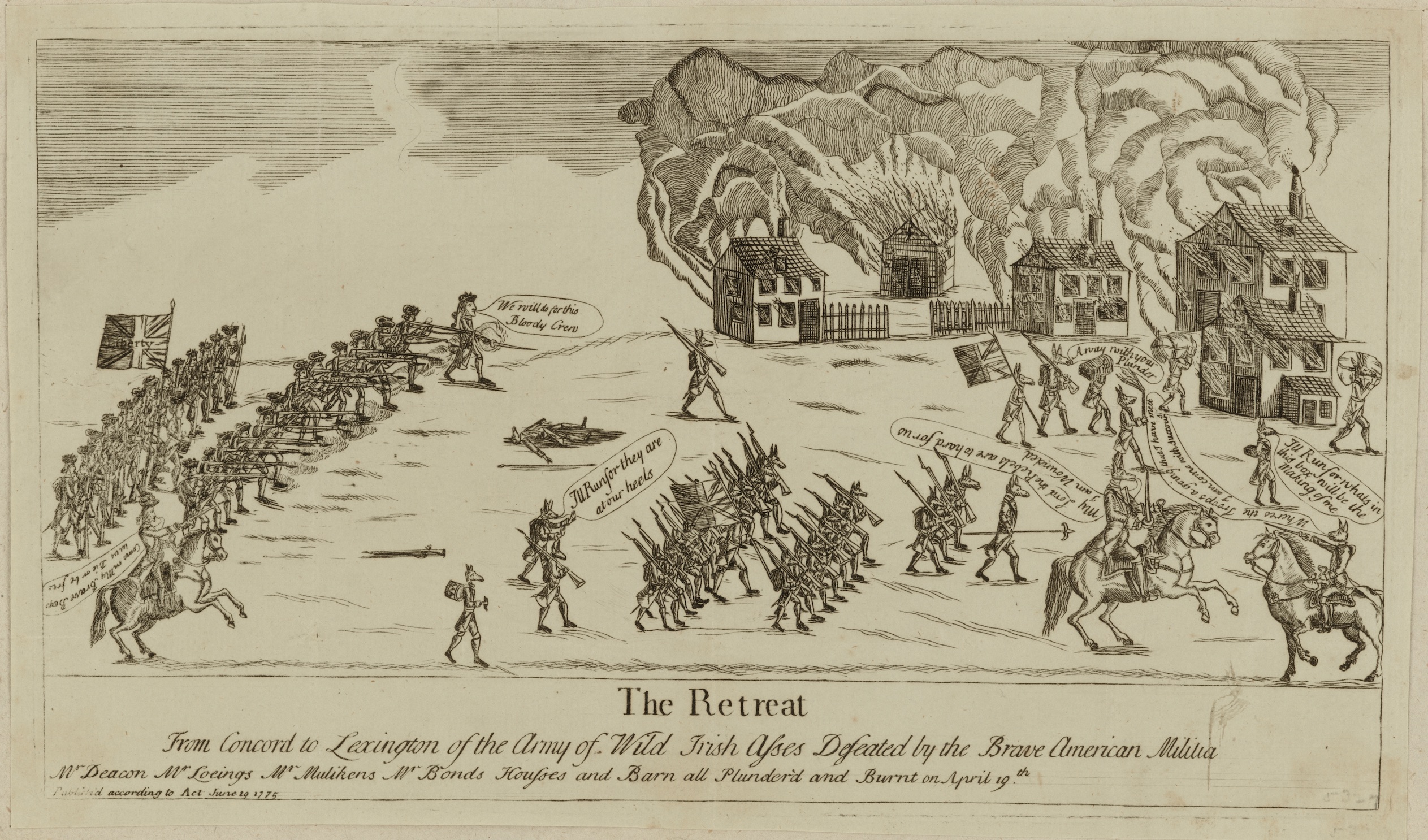

The march turned into a bloody running battle. Militia used side roads and country paths to get ahead of the Regulars and fired on them as they passed. Companies of exhausted British soldiers stopped to fire back, but the Americans vanished into woods and over hills only to reappear farther down the road. Stone walls, a British officer wrote, “were all lined with people who kept up an incessant fire upon us.” Large parties of militia shot down redcoats at Meriam’s Corner and at a bend in the road on Elm Brook Hill. John Parker and men from the Lexington militia—survivors of the morning fight on Lexington Green—ambushed the Regulars from a hillside overlooking the road.

Colonists shot at the soldiers from the windows of roadside houses. Soldiers sent ahead to search houses for armed colonists were killed inside. Others killed anyone they found, armed or not, then looted their possessions and set their houses on fire. “We were totally surrounded with such an incessant fire as it’s impossible to conceive,” a British officer wrote. As the number of dead and wounded mounted, the marching column disintegrated into a frightened rabble. Many of the British soldiers, their ammunition gone, considered surrendering.

General Gage had worried that something bad would happen, and about the time Pitcairn’s men reached Concord he had ordered a whole brigade of British troops, about 2,000 men, to march west in support. The fresh troops met the exhausted, frightened survivors just east of Lexington and the column turned and marched toward Boston. The militia harassed them the whole way, but the Regulars managed to get back to city. The colonists had killed or wounded 272 of the king’s soldiers. The dead were scattered along the road. Colonists took their weapons, stripped the bodies, and buried many of them in shallow graves where they fell. The Regulars had killed over 100 colonists, but had accomplished nothing of any military importance. They had been sent to Boston to impose order and had started a war instead.

This is an excerpt from Freedom: The Enduring Importance of the American Revolution, a new history of the American Revolution from Lyons Press, is available at good bookstores throughout the country and online at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and other retailers.

This is an excerpt from Freedom: The Enduring Importance of the American Revolution, a new history of the American Revolution from Lyons Press, is available at good bookstores throughout the country and online at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and other retailers.

“Freedom is an essential, desperately needed book. Much more than a comprehensive, exhaustively researched, and highly engaging history of the American Revolution, Freedom is a timely reminder of how deeply we are the direct beneficiaries of the actions of people who changed our world forever. I learned something new on every page (including hundreds of — yes — entertaining and engrossing footnotes), and came away inspired to do my part to preserve our republic for future generations.” David Duncan, President, American Battlefield Trust