A few minutes before dawn on April 19, 1775, British troops on an expedition to confiscate arms stored in Concord, Massachusetts, fired on armed militiamen on the Lexington Green. They killed eight men and wounded nine others. The remaining militiamen dispersed. The British troops then reformed and marched on toward Concord. The whole event, from the time the British troops came within sight of the militia to the time they resumed their march, took only a few minutes.

Reports that British troops had killed militiamen in Lexington spread very quickly, and when the British reached Concord militiamen there were prepared to resist. The two sides exchanged fire and several men — British Regulars as well as militia this time — were killed. The British ransacked the town but found few weapons. Then they withdrew, returning to Boston the way they had come, fighting a running battle the whole way with militiamen who fired from both sides of the road.

By the time the British troops reached Boston colonists had killed or wounded 272 of the king’s soldiers. The dead were scattered along the road. Colonists took their weapons, stripped the bodies, and buried many of them in shallow graves where they fell. The Regulars had killed over 100 colonists but had accomplished nothing of military importance. They had been sent to Boston to impose order and had started a war instead.

Since that morning Americans have tried to understand what happened at Lexington. The British reported that a colonist fired the first shot. American witnesses testified at the time that no American fired at all. Many years later Lexington men reported that some of them had fired after the first British volley, while other participants continued to deny it. In the 1820s there were old men in Lexington anxious to claim the honor of having been the first Americans to fire in the Revolutionary War and old men in Concord equally anxious to deny them that honor and claim they were the first Americans to offer armed resistance to the British.The skirmish in their town, they insisted, was the first battle of the Revolutionary War.

The documentary record is confusing and contradictory. The encounter at Lexington took place in the half light just before dawn. As soon as the British troops fired smoke obscured the green, making it hard to see who was shooting, limiting anyone’s view to what was happening immediately around him. The noise of battle — volleys and scattered shots mixed with shouts and the cries of wounded men — added to the confusion. Men naturally remembered it in different ways, depending on where they stood, what they did, and what they could see and hear, and over time their recollections were shaped by what other men said they remembered. Sorting the evidence and reconstructing what happened will always be very difficult.1

Yet Americans have been trying to imagine the Battle of Lexington — colonists called it a battle even while insisting that none of them fired — ever since it happened. Much of what Americans imagine about that morning has been shaped by a succession of artists, each trying to make sense of the event in a way that was relevant to his own time and consistent with what Americans believed, or wanted to believe, about the Battle of Lexington.

“we did not even return the fire”

The first published reports of the encounter at Lexington described it as an unprovoked massacre of innocent men gathered to defend their homes. The most widely circulated was published two weeks after the event in Isaiah Thomas’ Massachusetts Spy:

A company of militia, about 80 men, mustered near the meeting-house, the troops came in to sight of them just before sun-rise; the militia upon seeing the troops began to disperse. The troops then set out upon the run, hallowing and huzzaing, and coming within a few rods of them, the commanding officer accosted the militia in words to this effect, “Disperse ye damn’ed rebels! damn you disperse!” Upon which the troops again huzzaed, and immediately one or two officers discharged their pistols, which were instantaneously followed by the firing of four or five of the soldiers, and then there seemed to be a general discharge from the whole body. It is noticed they fired upon our people as they were dispersing, agreeable to their command, and that we did not even return the fire. Eight of our men were killed and nine wounded; The troops then laughed, and damned the Yankees, and said they could not bear the smell of gun-powder.2

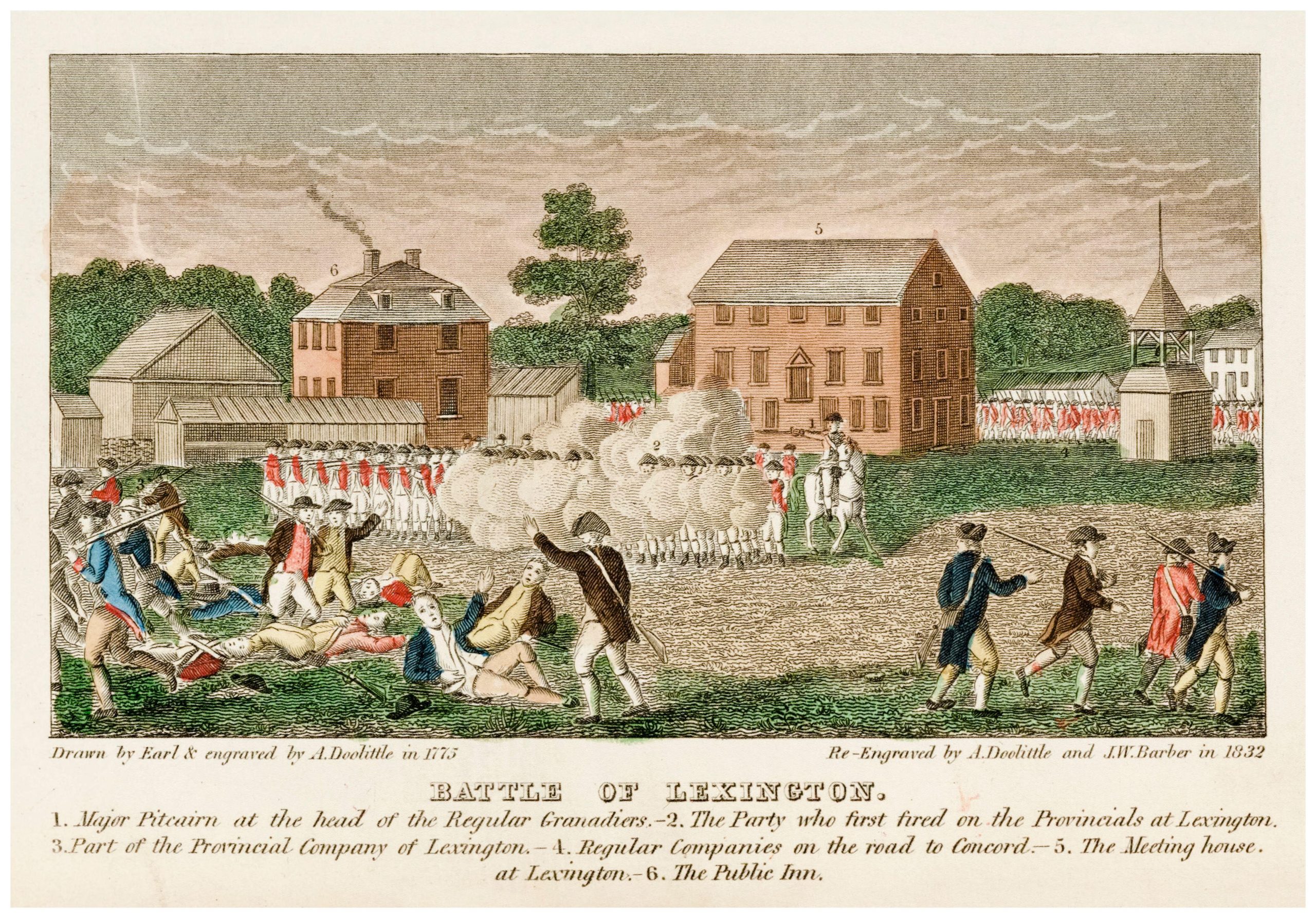

The first depiction of the event reflected this account of the battle. It was created by two young Connecticut militiamen, Ralph Earl and Amos Doolittle, neither of whom witnessed the encounter at Lexington. They visited the site a few weeks later and spoke with participants. Earl, who became an accomplished artist, drew a sketch of the confrontation. Doolittle, a silversmith, returned to New Haven where he engraved it on a copper plate from which he struck prints offered for sale in December 1775. Doolittle titled the engraving The Battle of Lexington April 19th 1775.3

Joseph Warren, president of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, charged that the British army had committed “barbarous Murders on our innocent Brethren” at Lexington. Amos Doolittle’s engraving of the scene reflected that view. Brown University Library.4

Although Doolittle titled the engraving The Battle of Lexington, the fighting looks entirely one sided. The militiamen don’t look organized or heroic. Most are leaving the scene. The British are delivering an organized volley and no American is returning fire. A few are looking toward the British but most are fleeing, leaving the green scattered with dead and wounded men.7

Fifteen-year-old St. John Honeywood of Leicester, Massachusetts, made this remarkably detailed copy of the Doolittle engraving about 1778. He made copies of the other three Doolittle engravings as well. Later painted copies suggest that the prints were known in New England but probably not much farther afield. Courtesy Swann Galleries.

Earl and Doolittle apparently chose this moment to depict Lexington militiamen as victims of British tyranny. Paul Revere had the same purpose for his engraving of the Boston Massacre but he marketed his engraving much more effectively. He published it three weeks after the massacre, when public interest was still high. The engraving sold very well and within weeks other print makers produced and sold copies as well.8 Doolittle published his engravings six months after the fighting on April 19. By then popular interest had shifted to more recent events. Doolittle probably sold a few hundred copies of each of his four engravings, but no print maker copied them.

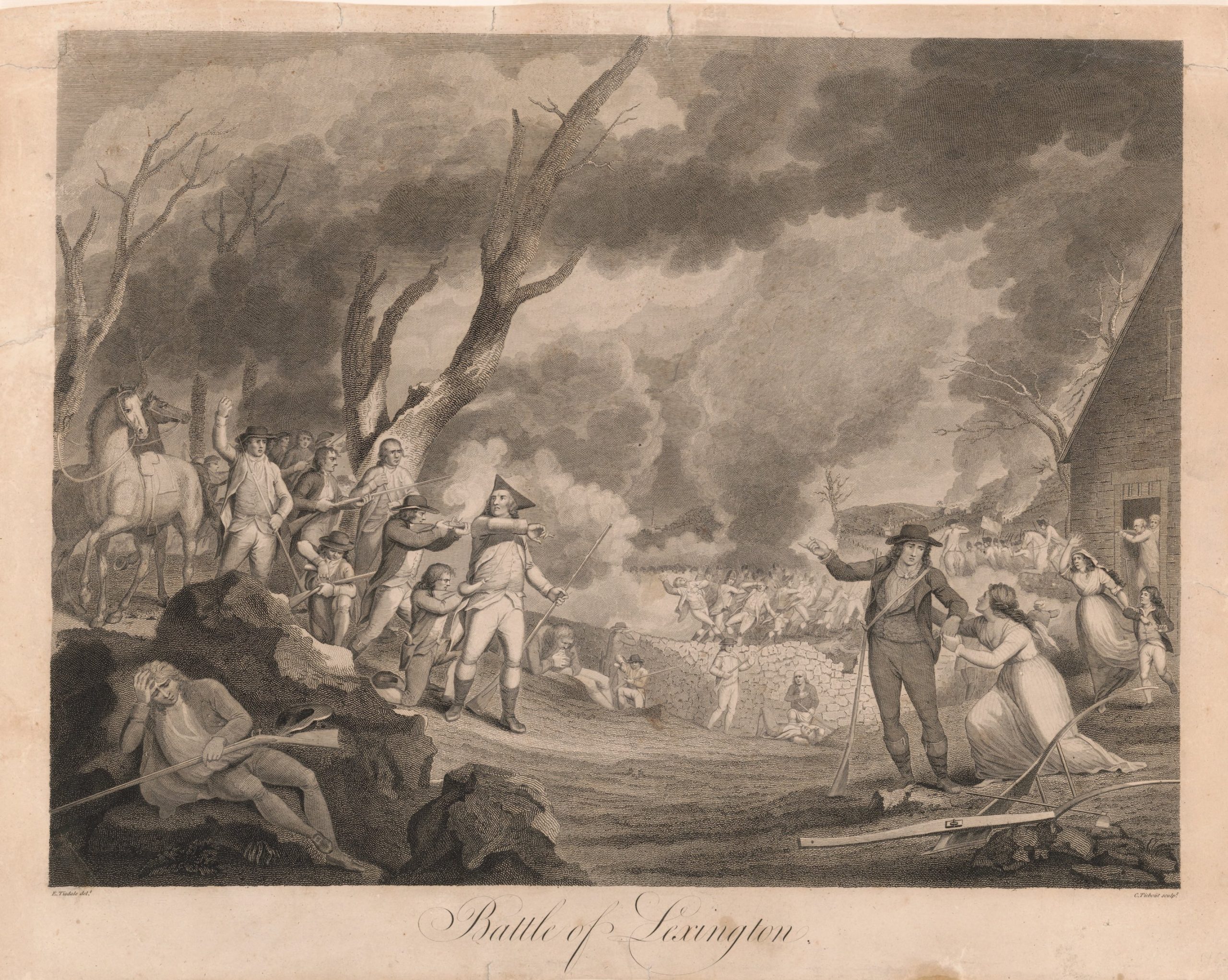

Cornelius Tiebout’s 1798 copperplate engraving Battle of Lexington was based on a design by Elkanah Tisdale, who was known chiefly for miniature portraits. Tisdale was from Lebanon, Connecticut, and had no first-hand knowledge of the confrontation at Lexington. His depiction of the fight is wholly imaginary and depicts the running battle along the road between Concord and Boston. Library of Congress.

After the war print makers satisfied the market for images of the first day of the Revolutionary War with wholly imaginary scenes of colonists firing on the British Regulars as they withdrew from Concord to Boston on the afternoon of April 19. The most ambitious was a copperplate engraving titled Battle of Lexington engraved by Cornelius Tiebout after a work by Elkanah Tisdale. Published in 1798, it depicts colonists firing on a marching column of British Regulars from behind trees and stone walls. Many nineteenth-century printmakers and publishers followed Tiebout, labeling images of colonists firing from cover, some of them based on the Tiebout engraving, as the Battle of Lexington.9

First Blow for Liberty, engraved by Alexander Hay Ritchie after a painting by Felix Octavius Carr Darley (New York, Mason Bros., 1858), is the finest of the many nineteenth-century prints depicting colonists firing on the British during their return to Boston on the afternoon of April 19. Most of the casualties on both sides — 272 British solders and some 100 colonists killed or wounded — occurred during this running battle. William Munroe Special Collections at the Concord Free Public Library.

“The scene represented . . . cannot with any propriety be called a battle”

Artists paid no further attention to the Battle of Lexington until the 1820s, when Connecticut engraver John Warner Barber produced the first new image of the confrontation on Lexington Green in almost fifty years.10 Trained in wood and copperplate engraving, Barber began his career in Hartford in 1819. In 1823 he engraved illustrations for the second edition of Charles Goodrich’s History of the United States, which went through dozens of editions and became one of the most widely used American history textbooks of the mid-nineteenth century. Among them was a wood engraving titled “Battle of Lexington,” very loosely based on the Doolittle engraving.11

John Warner Barber made his first wood engraving of the Battle of Lexington for Charles Goodrich’s History of the United States. To fit the scene in a small square format, Barber oriented the observer at eye level and crowded the militia together, compressing the action. The militiamen are dispersing while the Regulars fire a volley. None of the Americans is firing back.

The extraordinary success of Goodrich’s History of the United States must have stirred Barber’s imagination. In 1823, at twenty-five, he moved to New Haven and established himself as a writer and publisher of history books for ordinary Americans. Interest in American history was growing and Barber worked to satisfy that interest with a steady stream of books illustrated with his own wood engravings, including new depictions of the Battle of Lexington.12

In 1824 — just as Barber was setting up his business in New Haven — that battle became the center of a controversy between residents of Lexington and neighboring Concord. By then the men of Lexington were no longer content to remembered as victims and asserted that some of the militiamen returned the fire of the British Regulars.

The controversy boiled over that fall, when the marquis de Lafayette visited both towns. Lafayette arrived in Lexington on the morning of August 21 and was received with pomp and ceremony on the common where the militia had confronted the British Regulars. As Lafayette was preparing to leave, a young man approached him with a rusty musket, which he said “was the musket from which the first fire was returned to the English, upon the field of Lexington.”13 An account published in Boston a few weeks later reported that it was the gun “from which was fired the ball, which killed the first of the regular troops slain on that memorable occasion.” This was impossible, since no British soldier was killed at Lexington.14

Lafayette and his party rode on to Concord. His hosts there assured the old general that he was on “the spot on which the first forcible resistance was made.” Lafayette expressed regret at not seeing the battleground — the reception was held in a tent in the village, far the site of the Old North Bridge, which had been dismantled in 1793. The first shot fired there, he added graciously, “was the alarm gun to all Europe, or as I may say the whole world. For it was the signal gun, which summoned all the world to assert their rights and become free.”15

Lafayette’s secretary, Auguste Levasseur, wondered why they had gone to Concord, since it was so close to Lexington. He had no idea of the controversy between the towns, though he might have realized it a few days later when Concord delegates arrived in Boston to show Lafayette the musket used at Concord to shoot “the first British regular killed in the war of the revolution.”.16

Determined to settle the matter, Elias Phinney of Lexington collected the recollections of surviving Lexington militiamen in his History of the Battle at Lexington, on the Morning of the 19th April 1775, published in 1825. Some of them explicitly reported returning the fire of the British after the first of the militia fell. Rev. Ezra Ripley of Concord promptly responded with A History of Fight at Concord, on the 19th of April, 1775 . . . showing that then and there the first regular and forcible resistance was made to the British soldiery, and the first British blood was shed by armed Americans, and the Revolutionary War thus commenced. Ripley insisted that Lexington militia did not return fire and that Lexington was simply the scene of “blood and massacre.”17

Barber was familiar with these claims when he published a new wood engraving of the Battle of Lexington in his book Historical Scenes in the United States, or, a selection of omportant and interesting events in the history of the United States, in 1827. Aimed at young readers, the featured forty-eight numbered wood engravings beginning with the Indians before European settlement and ending with Lafayette’s visit to the United States. In addition to the Battle of Lexington, Barber engraved eleven scenes from the Revolutionary War for the book, including the Battle of Bunker Hill, New Yorkers toppling their statue of George III, Washington assuming command of the Continental Army, the battles of Trenton, Saratoga, and Stony Point, the murder of Jane McCrea, Israel Putnam’s escape from the British (a favorite of Barber’s Connecticut readers), the capture of John André, and the surrender of Cornwallis.

Barber created this second version of the Battle of Lexington for his own Historical Scenes in the United States (Monson and Company: New Haven, 1827). Like its predecessor, it depicts a line of British Regulars in front of the meeting house firing on the Lexington militia. Five men lie dead or wounded on the ground. One of them, with his left arm raised, is drawn from a figure in the Doolittle print. Others are fleeing.

It’s easy to underestimate the influence of such simple prints, which are crude compared to the mezzotints, aquatints, and other fine prints of the time, as well as to later steel engravings. But those prints were expensive and their circulation limited. Prints by wood engravers like Barber were inexpensive to produce and the books they embellished were sold for prices ordinary American could afford. Wood engravers freely copied and adapted each other’s work and their images appeared in an ever-increasing volume of books, pamphlets, newspapers, and magazines. They shaped the way Americans imagined their past. Then, as now, people were drawn to pictures.

William H. Lyon, a sailor born in 1842, etched the depiction of the Battle of Lexington from Barber’s Historical Scenes in the United States in a whale’s tooth sometime in the middle of the nineteenth century. Courtesy Robert C. Eldred Company.

Barber understood this as well as anyone. As illustrator, writer, and publisher he cultivated a reputation for authenticity, or what he called “correctness.” He visited many of the places he depicted and based his engravings on sketches and wash drawings he made on the spot. But illustrating historical events was much more difficult. He based this work on “the most authentic sources” available, with the ultimate aim of leading his readers “into the thoughts, hopes and aspirations of generations before us.”18

Barber particularly admired Doolittle’s engravings of Lexington and Concord, which he described as “the first regular series of historical prints ever published in this country.” He knew, from having visited Lexington, that Doolittle’s depiction of the town was a “faithful representation.” He was, he wrote, “personally acquainted with Mr. Doolittle,” the patriarch of New Haven’s engravers, and had “conversed with him repeatedly upon the subject of these drawings.”19

Doolittle explained to Barber that he had “acted as a kind of model for Mr. Earl to make the drawings, so that when he wished to represent one of the Provincials as loading his gun, crouching being a stone wall when firing on the enemy, he would require Mr. D. to put himself in such a position.” Doolittle added: “Although rude, these engravings appear to have made quite a sensation; particularly the battle of Lexington, where eight of the provincials are represented as shot down, with the blood pouring from their wounds.”20

Barber was convinced of the “correctness” of Earl and Doolittle’s representation of the confrontation at Lexington. In 1831 he persuaded Doolittle to assist him in preparing a new engraving of the event based closely on the original. According to Barber, they finished the print on the last day Doolittle was capable of working. Doolittle died on January 31, 1832. A short time later Barber published the print in his History and Antiquities of New Haven.21

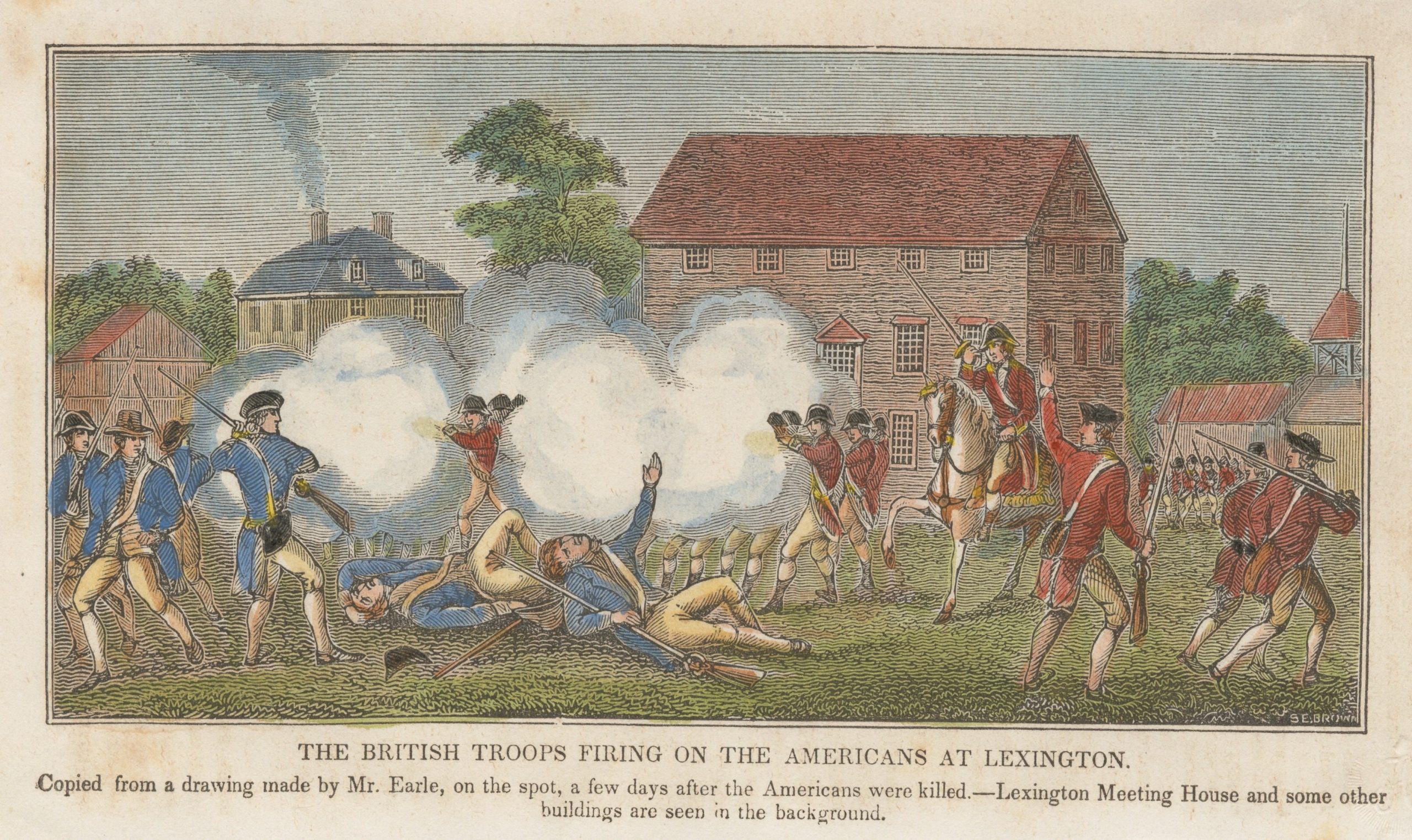

In his third engraving of the Battle of Lexington, Barber copied many of the details in the Doolittle engraving, but brought the perspective down to eye level and placed the viewer close to the action. He compressed the scene and simplified the composition by depicting half as many militiamen standing and fleeing. Both prints included eight men killed our wounded on the ground.

The influence of the Barber engraving far exceeded its merits as an example of the printmaker’s art. It was simple, but its proportions were well suited to books and magazines. The print was easy for other wood engravers to copy, alter, and adapt. Versions of it were published and republished for the rest of the nineteenth century.

Samuel Emmons Brown engraved “The British Troops Firing on the Americans at Lexington” for Barber’s The History and Antiquities of New England, New York and New Jersey (New Haven: J.W. Barber, 1841). This was the first of many published images based on Barber’s 1831 engraving.

Ironically, Barber didn’t think the encounter on Lexington Green was a battle at all. “The scene represented in this engraving cannot with any propriety be called a ‘battle,’” he wrote, “though thus spoken of by most historians. It is memorable only as the spot where the first American blood was shed; where the first American life was taken, in the Revolution.”22

Barber did not believe that any of the Lexington militia fired at the British on the morning of April 19. Like Ezra Ripley and Amos Doolittle, Barber believed that the Lexington men were dispersing when the British opened fire and that none of them had fired back. In 1839 Barber quoted Sylvanus Wood, a militiaman from Woburn who stood with the Lexington militia that morning. “There was not a gun fired by any of Captain Parker’s company within my knowledge,” Wood said in 1826. “I was so situated that I must have known it, had any thing of the kind taken place before the total dispersion of our company.”23

“a part of the fugitives stopped, and returned the fire”

The Battle of Lexington, lithograph by Moses Swett (Boston: Pendleton’s Lithography, [1830]). Yale University Art Gallery.

Moses Swett was the first artist to depict the Lexington militia firing at the British and the first to depict the lone British casualty of the encounter, shown on the ground at the end of the British line at upper right in this detail. Gilcrease Museum.

In 1835 Edward Everett delivered a lengthy oration at Lexington on the anniversary of the battle, concluding that “it was not till several of them had returned the British fire, and some of them more than once, that that this handful of brave men were driven from the field.” The advocates of Concord were unmoved. As if in reply, in 1837 Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote his “Concord Hymn” for the dedication of a monument where “the embattled farmers stood, and fired the shot heard round the world.”25

John Frost’s 1844 account of the clash at Lexington was accompanied by a half-page woodcut by William Croome of the militia engaged with the Regulars at close range with a wholly imaginary church in the background. One patriot engages the enemy with nothing more than a sword. Another swings his musket like a club.

Popular histories of the 1830s mostly supported the Concord view. John Frost, in his 1836 History of the United States, described the British regulars firing until the Lexington militia retreated, with no mention of the militia returning fire. Frost devoted a great deal more space to the fighting at Concord, which the publisher illustrated with a small woodcut.26 But by the early 1840s Frost had changed his mind. In his 1844 Pictorial History of the United States of America he wrote that as “the British continued to discharge their muskets after the dispersion, a part of the fugitives stopped, and returned the fire.”27

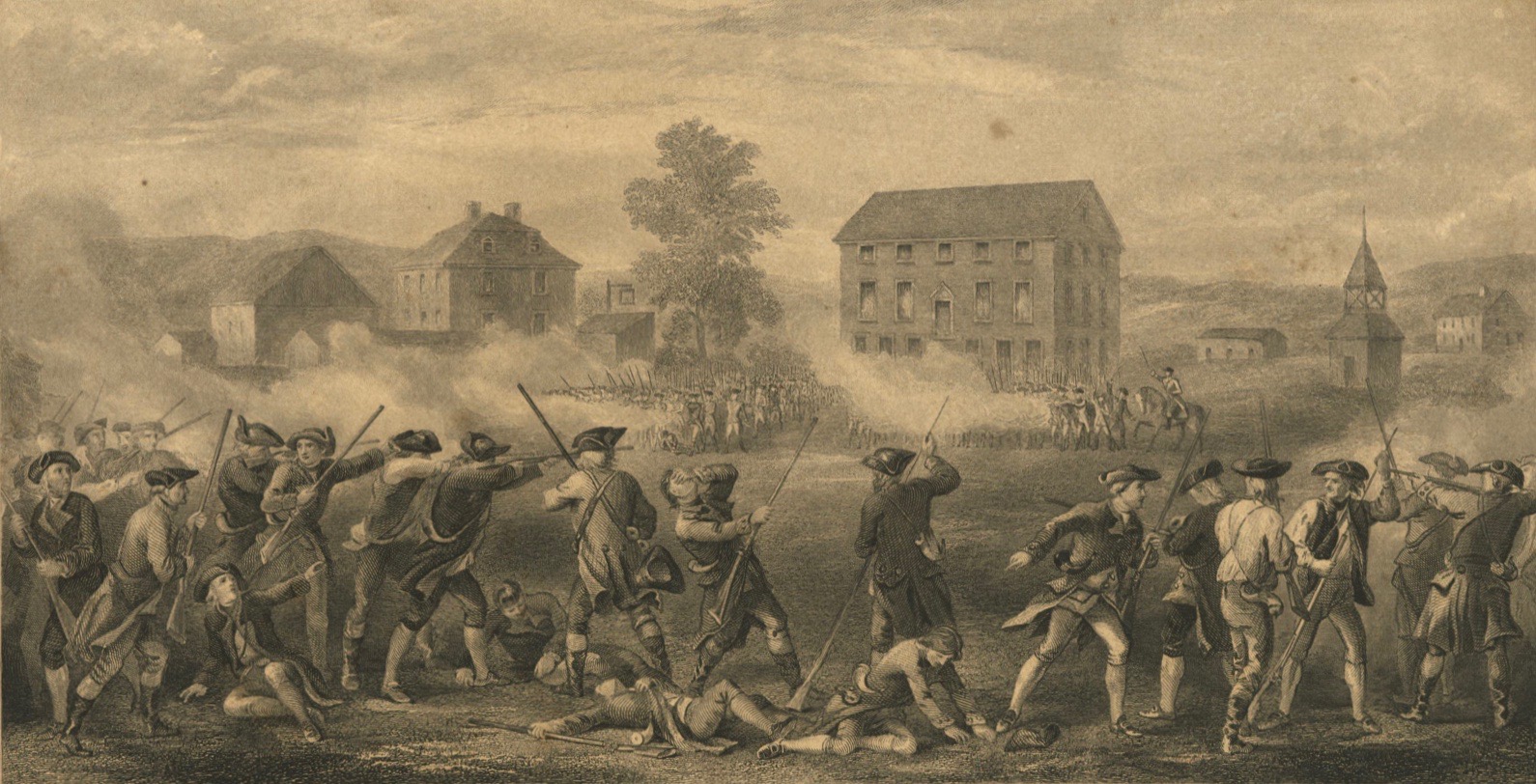

The number of courageous militiamen firing on the British grew in Alonzo Chappel’s The Battle of Lexington, painted around 1856 and engraved for Jesse Spencer’s four-volume History of the United States, published in 1858. The publisher of Spencer’s History commissioned Chappel to paint several original works for the series, all of which were carefully engraved on steel, printed, and bound into the work as full page illustrations. These were gift books, too expensive for school use, but their illustrations were widely reprinted in cheaper books and exerted considerable influence on how Americans imagined their revolution.28

Chappel’s version of the fighting at Lexington accompanied Spencer’s narrative explaining that after Pitcairn ordered the militiamen to throw down their arms and disperse, he “fired his pistol, and flourished his sword, while his men began to fire.” Several militiamen fell, Spencer wrote, and the rest dispersed, “but the firing on them was continued; and on observing this, some of the retreating colonists returned the fire.”29

James David Smillie engraved Alonzo Chappel’s version of the Battle of Lexington about 1858. Chappel placed the militia in the foreground and four militiamen are retreating at right, as they are in the Doolittle and Barber versions. The background is drawn from the familiar Barber composition — Buckman’s Tavern on the left and the meeting house at right center — but Chappel shifted the orientation of the antagonists so the British are charging across the front of the meeting house, compressing the action to build dramatic tension. The British Regulars and the Lexington militia are on only a few yards apart. A British officer on horseback, presumably Major Pitcairn, is just a few feet from the patriot line. The flash of gunfire above and behind the militiamen in the foreground may come from the muskets of unseen Americans or those of advancing Regulars. The visual confusion makes it impossible to be certain. Emmet Collection, New York Public Library.

Chappel’s dramatic treatment of the battle departed considerably from this account. Chappel regarded himself as an independent interpreter of the events he depicted on canvas, much like contemporary history painters Emanuel Leutze, Peter F. Rothermel, William Tylee Ranney, and Christian Schussele. Like them, Chappel took liberties with documented facts in order to convey important ideas — in this case the courage of the patriots in resisting the armed might of Britain, which is underscored by the advancing ranks of British infantry, the confusion and chaos in the foreground, and the disciplined militia firing at left. The visual confusion makes it impossible to be certain.

While the militia in the foreground engage the enemy at close quarters, the men in the background, some wearing uniforms, are deployed in two lines and fire an organized volley at the command of an officer with a sword. The disciplined ranks in uniform seem to foreshadow the long war to come. This part of the composition is entirely original to Chappel and is not consistent with any contemporary description of the encounter on Lexington Green. It is however consistent with the rising nationalism of the 1850s — a spirit that shaped Chappel’s work.

“if they mean to have war, let it begin here”

Something more than local and national pride shaped the version of the battle created in 1859 by Hammatt Billings, who was skilled in a broad range of arts, including graphic design, book illustration, and architecture. He designed elegant funerary monuments and elaborate public memorials, including a marble canopy constructed over Plymouth Rock and a national monument to the Pilgrims consisting of an enormous granite statue of Faith flanked by allegorical figures of morality, education, law, and liberty. His work — including his depiction of the Battle of Lexington — is richly symbolic.

Asa Coolidge Warren engraved Hammatt Billings’ depiction of the battle, intended for a bronze plaque to be attached to a monument on the Lexington Green that was never built. This is a detail from the Lexington Monument Association membership certificate (Boston: Smith & Knight, 1861). Scottish Rite Masonic Museum & Library, Lexington.

Billings’ depiction of the Battle of Lexington was based on the Barber image, but Billings filled the foreground with militiamen firing on the enemy. Billings intended this image to be cast in bronze and attached to the pedestal of a monument on the Lexington Green topped by a colossal bronze statue, described by Edward Everett as “the figure of a Minute-Man, who, leaving his accustomed labors, and seizing his musket . . . has hastened to confront the disciplined battalions of arbitrary power.” Billings’ battle image was published several times — first in 1861 on the membership certificate of the Lexington Monument Association, in 1868 in Charles Hudson’s History of the Town of Lexington, and later in connection with a less ambitious but nonetheless powerful monument on the Lexington Green.30

Billings’ image of the battle is a symbol of unity and national purpose from a time when public life was dominated by a mounting crisis over slavery that endangered the Union and the liberty for which the revolutionary generation had fought. Like many of his New England contemporaries, Billings connected the struggle for liberty in the revolutionary era with the antislavery movement of his own time. He was committed to abolition — he redesigned the masthead of William Lloyd Garrison’s abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator, without charging Garrison for the work, and provided graphic designs for the first edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a full set of illustrations for the editions of 1852 and 1853, and illustrations for antislavery works by Richard Hildreth, Charles Sumner, and John Greenleaf Whittier. Billings was equally committed to the Union, which was increasingly threatened by southern sectionalism and threats of secession.31

In the later 1850s the resistance of the Lexington militia came to symbolize resistance to the “Slave Power.” They were tied together by the Reverend Theodore Parker of Boston, whose grandfather Captain John Parker had commanded the Lexington militia on April 19, 1775. On trial in Boston for inciting a riot against the Fugitive Slave Act, Reverend Parker explained that he was inspired to resist the Slave Power by faith and commitment to the high ideals of the Revolution, inherited from his grandfather, who had told his men: “Don’t fire unless fired upon, but if they mean to have a war, let it begin here.” According to his grandson, Captain Parker had defied the armed might of Britain and invited a war of liberation. The implication was clear: rather than surrender to the Slave Power, Reverend Parker was prepared for a war for liberty and Union.32

Like Moses Swett, Billings was attentive to an important historical detail: at the center of the image, Billings depicted the one British soldier known to have been wounded in the exchange — proof that the militia fired on the British at Lexington.33

Billings’ version of the action on Lexington Green is a tableau memorializing those ideals rather than a literal depiction of the action. Billings carefully delineated each militiaman, emphasizing his individuality and autonomy and thus his personal commitment to a cause larger them himself. Facing a powerful foe, none shrinks from the fight. The effect is a visual allegory of free men united in the sacred cause of liberty, reminiscent of a classical frieze. Because his enemies include all opponents of universal liberty, Billings pushed the redcoats to the background, distant and obscured by the smoke of battle. Interrupted by the war for the Union, the colossal monument was never built, but the succession of Lexington battle scenes, copied and duplicated in books and magazines, sustained the idea that what had happened at Lexington was the first battle of the Revolutionary War.

John McNevin’s Battle at Lexington, engraved by John Rogers in 1860 for Benson Lossing’s Life of Washington, is the most unusual image of the battle published in the nineteenth century. In the foreground McNevin depicted Jonathan Harrington, who was reported to have been crawled to his front door after being shot. Militiamen in the background are exchanging fire with the British while Harrington dies in his wife’s arms. New York Public Library.

Harper’s Weekly published a half-page wood engraving of the battle in April 1869. The accompanying text described it as a “a sketch of the skirmish at Lexington, copied from a print published a short time after the conflict occurred,” referring to the Doolittle engraving. The artist followed the Barber model, including a confused withdrawal on the left, dead and wounded in the foreground, and a militiaman with his left arm raised at the center. Like Barber, he included four militiamen in the right foreground, but instead of retreating three are facing the enemy. One of them is firing — his pose is identical to a figure at far right in the Billings version of the battle. The print includes four other militiamen defiantly facing the British.34

Citizens of Concord nonetheless continued to insist that the first American shots of the war were fired in their town. They belatedly reconstructed the Old North Bridge and on the centennial of the Battle of Concord — April 19, 1875 — they dedicated a statue by Daniel Chester French, The Minute Man, on the side of the bridge where the Concord militia stood their ground. Emerson spoke at the dedication and recited his “Concord Hymn.” The statue stood on a pedestal bearing the first stanza of the poem. Lexington, a prominent resident of Concord wrote, was simply a “cold-blooded massacre.”

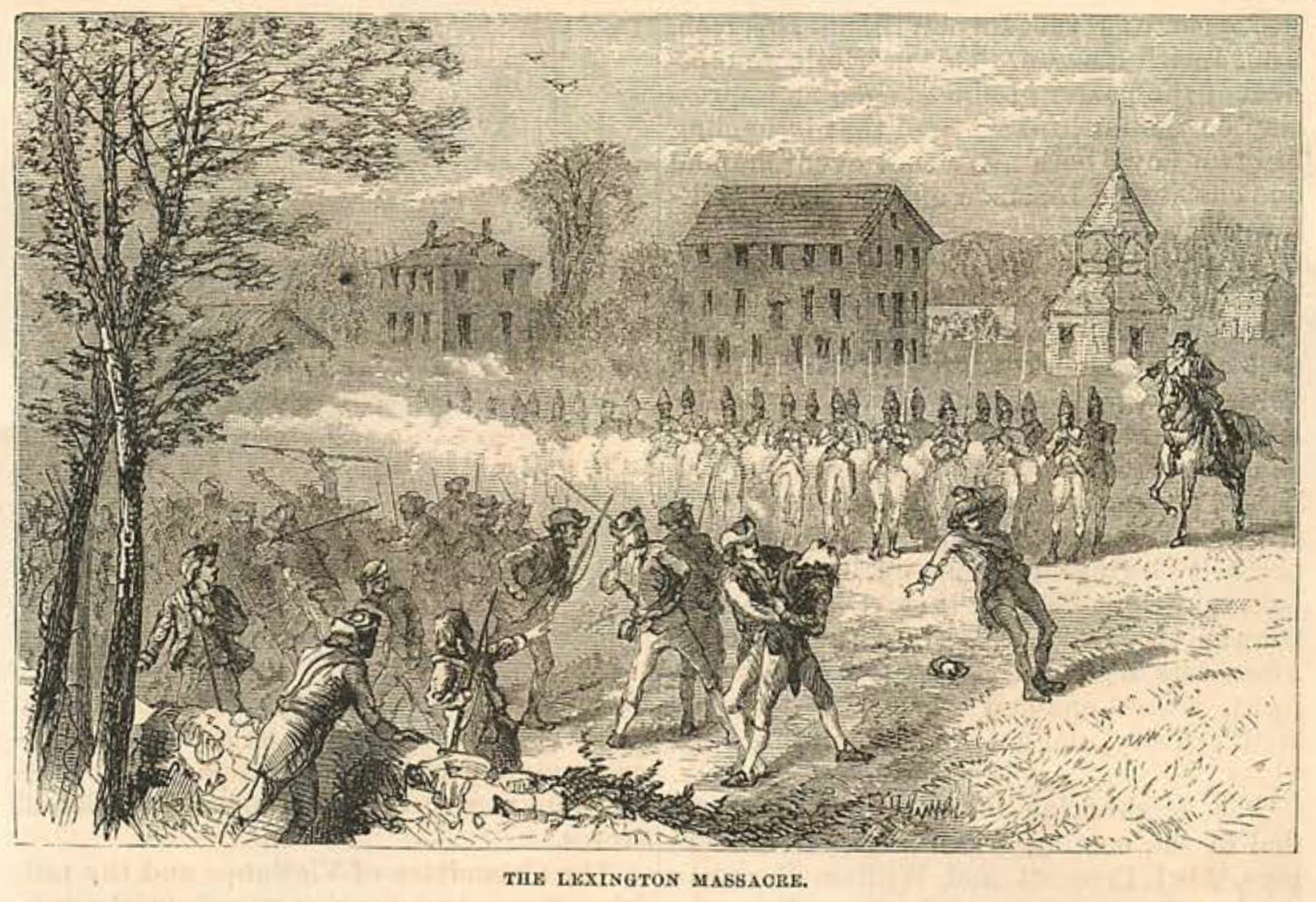

Harper’s New Monthly Magazine celebrated the dedication of The Minute Man with a special issue on “The Concord Fight,” in May 1875. It included this wood engraving of “The Lexington Massacre.”

Dawn of Liberty

By 1875 that argument was losing ground, thanks in no small way to the stream of published images of the Battle of Lexington. In the last twenty years of the nineteenth century a succession of painted and printed depictions of the clash on Lexington Green fixed the battle in the popular imagination.

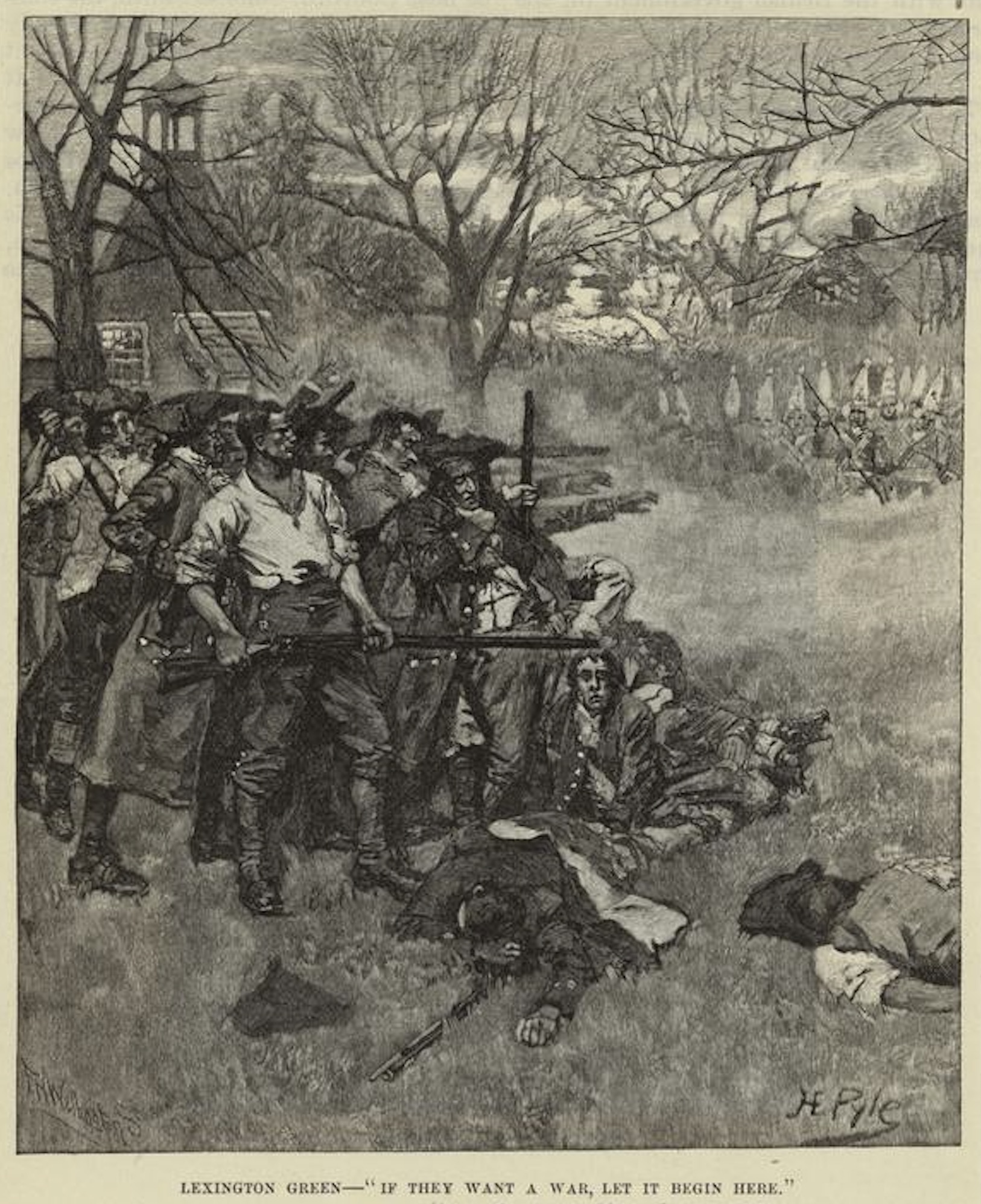

In contrast to the chaos depicted by Alonzo Chappel, Howard Pyle portrayed the Lexington militiamen massed to meet their foe, grimly determined despite the dead and wounded men at their feet. They crowd together for mutual support, forming a firing line and a metaphorical line between peace and war. New York Public Library.

The first was the work of a young artist, Howard Pyle, who was to become of the leading illustrator of his generation. The October 1883 Harper’s New Monthly Magazine published an engraving of his new painting, “Lexington Green — “If they want a war, let it begin here.” It accompanied an article by Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a Unitarian minister and abolitionist protégé of Theodore Parker who memorialized the words Reverend Parker attributed to his grandfather: “‘Don’t fire unless you are fired on; but if they want a war, let it begin here.’ It began there; they were fired upon; they fired rather ineffectually in return.”35

In April 1884 the citizens of Lexington memorialized that spirit by placing a large granite boulder on the spot where the militia had made its stand. At the top they carved “Line of the Minute Men.” Below they carved the words Reverend Parker had attributed to his grandfather, though no contemporary recalled Captain Parker saying “if they mean to have a war let it begin here.”36

In Dawn of Liberty Henry Sandham placed the observer behind the right end of the patriot line. He based his composition on the Barber image, including the militiaman with an arm raised in the foreground. The British have already fired, leaving crumpled American victims on the ground, but the remaining militia display the same grim determination depicted by Pyle. Indeed the militiaman in the left foreground adopts the same defiant pose as the central figure in Pyle’s Lexington Green. Sandham was the first artist to set the battle in the half-light of dawn, an innovation based on contemporary reports that the regulars arrived at Lexington at five o’clock or shortly thereafter — just before sunrise.37 Lexington Historical Society, Lexington, Massachusetts.

The memorialization of the battle and the success enjoyed by Chappel, Billings, and Pyle encouraged other artists to take up the theme. Among them was Henry Sandham, a Canadian-born painter who settled in Boston in 1880. He completed his painting of the battle, The Dawn of Liberty, in 1886. The newly formed Lexington Historical Society promptly bought it, fulfilling what the society called “a long-felt desire among our citizens to possess a picture preserving upon canvas the landmarks of the old battle-ground, and representing an ideal of the stand for right made thereon on the 19th of April, 1775.”38

Like Billings, Pyle depicted the lone British casualty of the engagement, seen on his knees at right center. He had been shot in the thigh. Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington, Delaware, Museum Purchase, 1912.

Howard Pyle returned to the theme in 1898 with The Fight on Lexington Common, April 19, 1775, one of twelve paintings Scribner’s commissioned from him to accompany The Story of the Revolution by Henry Cabot Lodge, which was published serially in Scribner’s Magazine and thereafter in book form. Pyle improved on the composition of Sandham’s Dawn of Liberty by including the faces of militiamen, achieved by portraying some looking toward unseen foes on the viewer’s right. They include the faces of old men and boys who display a range of emotions, including shock and fear as well as the determination on display in Pyle’s 1883 painting of the battle. These are ordinary people made extraordinary by their involvement in an event of transcendent importance.39

In The First Fight for Independence, William Barnes Wollen captured the shock and confusion following a British volley that left dead and wounded militia on Lexington Green. National Army Museum, London, England.

By the beginning of the twentieth century representations of courageous militiamen stubbornly returning British fire were so widely accepted that a British artist imagined the clash at Lexington that way. William Barnes Wollen, a professional illustrator who specialized in battle scenes, adopted the composition employed by Pyle for his 1910 painting, The First Fight for Independence. In a long career painting scenes from British military history — mostly from the Napoleonic Wars, the Boer War, and World War I — this was Wollen’s only painting of the American War of Independence. He was probably not aware that his composition could be traced to an eighteenth-century American engraving of British Regulars firing on militiamen who weren’t firing back.40

In the battle over the Battle of Lexington, the painters won. Despite Earl and Doolittle’s efforts to produce an accurate image of what happened at Lexington Green and regardless of Barber’s commitment to “correctness,” the idea that the Lexington militia stood its ground and exchanged fire with the British Regulars still shapes how Americans imagine the Battle of Lexington.

Stand Your Ground, painted by Don Troiani in 1985, differs only slightly from the paintings of Pyle and Wollen, but those subtle differences matter. Accounts by participants demonstrate that at least a few militiamen stood their ground, if only for a moment. Troiani depicts just seven militiamen. Perhaps the rest are fleeing. The man at far left appears to be retreating, but this isn’t certain. It isn’t clear whether the man on his knees behind the man in the gray coat is wounded or is reloading. The militiaman in the brown coat at left appears to have just been hit, but this isn’t clear either. The painting reflects the uncertainties that cloud our understanding of what happened on Lexington Green. National Guard Bureau.

Notes

- The difficulty has not stopped many writers from trying, including me. See Jack D. Warren, Jr., Freedom: The Enduring Importance of the American Revolution (Essex, Connecticut: Lyons Press, 2023), 117-19, 393. The most judicious and carefully documented account is in David Hackett Fischer, Paul Revere’s Ride (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 184-201, 399-403. [↩]

- The Massachusetts Spy, or, American Oracle of Liberty, [Worcester], May 3, 1775. [↩]

- The modern scholarly work on Doolittle is Donald C. O’Brien, Amos Doolittle: Engraver of the New Republic (New Castle, Delaware: Oak Knoll Press, 2008). On the four engravings, see Ian M.G. Quimby, “The Doolittle Engravings of the Battle of Lexington and Concord,” Winterthur Portfolio, vol. 4 (1968), 83-108. In an otherwise useful study Quimby praises the Doolittle engravings as “realistic version of the events totally outside the heroic tradition that dominated historical painting at the time” and in contrast to the “heroic” treatment of subsequent artists. Actually historical painting in the English-speaking world was at a turning point in 1775, shaped by the revolutionary work of Benjamin West and his followers, including John Trumbull, who abandoned conventions that had dominated historical painting since the Renaissance. West’s style was too new to have been a tradition in 1775. The Doolittle engravings belong instead to the tradition of Anglo-American polemical prints of which Paul Revere’s The Bloody Massacre perpetrated in King Street (1770) is an outstanding example.

Doolittle identified himself as the engraver but did not include Earl’s name, probably because by December Earl had disclosed the loyalist sympathies that ultimately led to his departure for England, where he trained as a painter. The attribution of the underlying sketch to Earl is based on an account by John W. Barber, a New Haven engraver who knew Doolittle decades later and sought his help in 1831 in creating a new engraving based on Doolittle’s original work (see note 4 below). According to Barber, Doolittle told him that he and Earl had gone to Lexington together and that Earl had drawn the scene. The original sketches are not known to survive. Quimby dismisses Barber’s story on the grounds that Earl was too good an artist to have drawn the crude figures depicted in the engraving, but this means that Doolittle lied to Barber or that Barber fabricated his account of his conversations with Doolittle. Neither Doolittle nor Barber had a discernible motive to attribute the drawings to Earl, who had been dead for thirty years, unless Earl drew them. Quimby nonetheless attributes the sketches to Doolittle. He does not address the possibility that Earl drew the scene, which demonstrates a rough workmanlike ability to depict perspective, and that the crude treatment of the figures is simply a consequence of Doolittle’s limitations as an engraver at the beginning of his career. [↩]

- “In Congress, at Watertown, April 30, 1775,” Broadside [Watertown: printed by Benjamin Edes, 1775], Massachusetts Historical Society. [↩]

- Doolittle advertised the set of four engraving for six shillings plain and eight shillings colored in the Connecticut Journal on December 13, 20, and 27, 1775. [↩]

- Hogarth produced several such series, including A Harlot’s Progress (1731), The Rake’s Progress (1735), Marriage à-la-mode (1743), Industry and Idleness (1747), in addition to The Four Stages of Cruelty ( 1751). They were among the most familiar English prints of the eighteenth century. Amos Doolittle was familiar with the genre. He engraved plates for a series of four prints of the Prodigal Son published by Shelden & Kennett of Cheshire, Connecticut, in 1814. [↩]

- Despite the one-sided nature of the encounter, it was immediately referred to as the Battle of Lexington. In The Massachusetts Spy, or, American Oracle of Liberty of May 3, 1775, Isaiah Thomas predicted that the 19th of April, 1775 . . . will be remembered in future as the Anniversary of the BATTLE of LEXINGTON!” [↩]

- These included Henry Pelham of Boston — from whom Revere had appropriated the design — Jonathan Mulliken of Newburyport, and William Bingley of London. Others published woodcuts and wood engraving of the image in books, pamphlets, and broadsides; for more on the Revere engraving, see “Lessons from the Boston Massacre” in The American Crisis. [↩]

- The Tiebout engraving bears neither place nor date of publication. The artist, Elkanah Tisdale (1768-1835), a miniature painter, graphic design, and minor engraver, lived in New York City from 1794 to 1798. No original of this work by Tisdale is known. The engraver, Cornelius Tiebout (ca. 1773-1832), spent 1793-96 in London, where he reported lived with Benjamin West and studied stipple engraving with James Heath, one of England’s most accomplished engravers. On his return to America he settled in New York, where he worked until the end of 1799 or the beginning of 1800, when he moved to Philadelphia. Battle of Lexington was published on January 1, 1798, by the New York firm of Cornelius and Alexander Tiebout as the first installment of a never-completed series titled “The Columbian War, or Battles for American Independence.” Gloria-Gilda Deák, Picturing America, 1497-1899: Prints, Maps, and Drawings Bearing on the New World Discoveries and on the Development of the Territory that is Now the United States (2 vols., Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988), 1: 141, praises Tiebout as “the first American-born engraver to produce really meritorious work.” See also E. McSherry Fowble, Two Centuries of Prints in America, 1680-1880: A Selective Catalogue of the Winterthur Museum Collection (Charlottesville: Published by the University of Virginia Press for the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, 1987), 306.

Artists labeled depictions of the afternoon fight along the road “The Battle of Lexington” as late as 1903, when Karl Jauslin (1842-1904), a Swiss artist, drew a version of colonists firing on the withdrawing British in charcoal (Sotheby’s sale, May 17, 1999). Images of fighting along the road are a distinct group. The settings are mostly generic and the action imaginary. Doolittle’s engraving A View of the South Part of Lexington might have served as a contemporary source but seems to have been unknown to nineteenth-century artists who depicted the fight along the road. Among the problem artists and historians faced — and still face — is that the fight along the road has no name. It is treated in books as part of the “Battles of Lexington and Concord” though the fighting was spread over several miles. Some of the most savage fighting took place in and around Menotomy, between Lexington and Cambridge. The battle was spread over several towns and the road went by various names, so no ready name for the battle presents itself.

European artists created fictitious images of the Battle of Lexington, including Daniel Nickolaus Chodowiecki, Das erste Bürger Blut, zu Gründung de Americanischen Freyheit, vergossen bey Lexington am 19ten April 1775 ([Berlin, be Haude und Spener, 1784]), and François Godefroy, Journée de Lexington (Paris, chez Mr. Godefroy . . . et chez Mr. Ponce [1785]). It seems unlikely that these prints were much known in America, if at all, before they came to the attention of antiquarian collectors in the late nineteenth century and subsequently through them passed into library collections. They certainly had no influence on American images of the battle. [↩]

- Barber apprenticed with Abner Reed in East Windsor, Connecticut, from 1813 to 1819. During those years Reed trained eleven other young engravers who subsequently plied the trade in New England and New York. This experience tied Barber to a wide network of engravers active in the second quarter of the nineteenth century. Barber maintained a diary, now preserved in the New Haven Museum and Historical Society (founded as the New Haven Colony Historical Society, which remains its corporate name), which was an important source for Donald C. O’Brien, “Training in the Workshop of Abner Reed,” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society (1995), 45-69. See also O’Brien’s “John Warner Barber: A Connecticut Engraver,” Imprint, vol. 4 (April 1979), 20-22; Richard Hegel, Nineteenth-Century Historians of New Haven (Hamden, Connecticut: Archon Books, 1971), 32-50; Chauncey C. Nash, “John Warner Barber and his Books,” Walpole Society Note Book (1934), 5-35; and Henry H. Townshend, “John Warner Barber, Illustrator and Historian,” Papers of the New Haven Colony Historical Society, vol. 10 (1951), 313-36. [↩]

- The engraving of the Battle of Lexington in Charles A. Goodrich, A History of the United States of America (Hartford: [John Warner] Barber & [D. F.] Robinson, 1822) is not signed but is readily attributed to Barber, who was one of the publishers. The manner in which the figures are engraved is very similar to Barber’s later engravings of the same scene. Elkanah Tisdale, coincidentally, drew some of the designs for wood engravings for the second edition of Goodrich’s History of the United States, including the first depiction of the Constitutional Convention of 1787. [↩]

- Barber’s output was prodigious. He wrote and illustrated dozens of books, including An Account of the Most Important and Interesting Religious Events, which have transpired from the commencement of the Christian era to the present time (1833), Connecticut Historical Collections: containing a general collection of interesting facts, traditions, biographical sketches, anecdotes, &c., relating to the history and antiquities of every town in Connecticut (1836), Historical Collections: being a general collection of interesting facts, traditions, biographical sketches, anecdotes, &c., relating to the history and antiquities of every town in Massachusetts, with geographical descriptions (1839), A History of the Amistad Captives (1840), Historical Collections of the State of New York (1842), Historical Collections of the State of New Jersey (1844), Historical, Poetical and Pictorial American Scenes (1850), and many others. Some of these books included hundreds of illustrations and some went through several editions. [↩]

- Auguste Levasseur, Lafayette in America in 1824 and 1825: Or, Journal of a Voyage to the United States, John D. Godman, trans. (2 vols., Philadelphia: Carey and Lea, 1829), 1: 54, 70. The more recent translation of these passages in Allen Hoffman, trans., Lafayette in American in 1824 and 1825 (Manchester, New Hampshire: Lafayette Press, 2006), 44, 70, differs slightly but in no important way from Godman’s translation. [↩]

- [Samuel L. Knapp], Memoirs of General Lafayette (Boston: E. G. House, 1824), 163. [↩]

- Concord Gazette and Middlesex Yeoman, September 4, 1824, p. 2; on the bridge, see Deborah Dietrich-Smith, “Cultural Landscape Report: North Bridge Unit, Minute Man National Historical Park, Site History,” 2004. Lafayette’s comment anticipated Ralph Waldo Emerson’s reference to the first shot at Concord as “the shot heard round the world.” [↩]

- The tent was only large enough to accommodate town officials, the welcoming committee, and a few veterans. Townsfolk anxious to get a glimpse of Lafayette were kept back by ropes and armed soldiers. “Well do I remember the insulting treatment I received when, among others, I attempted to look at Lafayette,” one later complained; “we had to stand back then at the point of the bayonet, whilst the great folks sat and drank at our expense.” On the reception, see Robert Gross, The Transcendentalists and their World (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021); for Levasseur’s puzzlement, see Levasseur, Lafayette in America, 71; on the musket shown to Lafayette on August 28, see Concord Gazette and Middlesex Yeoman, September 4, 1824, p. 2 [↩]

- Elias Phinney History of the Battle at Lexington, on the Morning of the 19th April 1775 (Boston: Phelps and Farnham, 1825), 20-22; Ezra Ripley, A History of Fight at Concord, on the 19th of April, 1775 . . . showing that then and there the first regular and forcible resistance was made to the British soldiery, and the first British blood was shed by armed Americans, and the Revolutionary War thus commenced (Concord: Allen & Atwill, 1827), 37. [↩]

- John Warner Barber, Historical Scenes in the United States or a Selection of Important and Interesting Events in the History of the United States. Illustrated by numerous Engravings (New Haven: Monson and Co., 1827), Preface (not paginated); John Warner Barber, Connecticut Historical Collections, Containing a General Collection of Interesting Facts, Traditions, Biographical Sketches, Anecdotes, &c., Relating to the History and Antiquities of Every Town in Connecticut, with Geographical Descriptions. Illustrated by 190 Engravings (2nd ed., New Haven: Durrie & Peck and J. W. Barber, 1836), iii. [↩]

- John Warner Barber, Historical Collections, Being a Collection of Interesting Facts, Traditions, Biographical Sketches, Anecdotes, &c., Relating to the History and Antiquities of Every Town in Massachusetts, with Geographical Descriptions. Illustrated by 200 Engravings (Worcester: Published by Dorr, Howland & Co., 1839), 398-99. [↩]

- John Warner Barber and Lemuel S. Punderson, History and Antiquities of New Haven, Conn., from the Earliest Settlement to the President Time. With Biographical Sketches and Statistical Information of Public Institutions, &c., &c. (2nd. revised ed., New Haven: L. S. Punderson and J. W. Barber, 1856), 157-58. Barber did not include these details with the first printing in 1831-32. [↩]

- Barber first published the engraving as a late addition to the first printing of his History and Antiquities of New Haven, (Conn.) from its Earliest Settlement to the Present Time. Collected and Compiled from the Most Authentic Sources (New Haven: J. W. Barber, 1831). The book was printed in 1831. Barber alluded to the sale of the four prints on p. 87, noting that “Mr. Doolittle is living and still pursues the business of engraving in this place.” After Doolittle’s death Barber added a signature of twelve pages, including the new print, making a second state of the book. The “Representation of the Battle of Lexington” is introduced on pp. 111-113, with the print on an unnumbered page facing 113. Barber certainly did not need Doolittle’s assistance to engrave this print. Although he probably consulted with Doolittle his assertion that the print was “Re-Engraved by A. Doolittle and J. W. Barber in 1832” seems like a device to claim the “correctness” of the Doolittle original for the new work. [↩]

- Barber and Punderson, History and Antiquities of New Haven, 158. [↩]

- Barber read the account of Sylvanus Wood in Ripley, A History of Fight at Concord, 54-55; he quoted it in his Historical Collections . . . of Every Town in Massachusetts, 400-1. [↩]

- A wood engraving of Swett’s image titled “The Battle of Lexington, April 19, 1775,” was used as the frontispiece to the 1875 reprint of Phinney’s book published by the Franklin Press, the trade imprint of Rand, Avery and Co., a Boston commercial printer. The wood engraving was apparently made for the reprint and should not be identified with the original 1825 edition, which preceded the Moses Swett lithograph by five years. [↩]

- Edward Everett, Address Delivered at Lexington on the 19th (20th) of April, 1835 (Charlestown, Massachusetts: William H. Wheildon, 1835), 20; The Concord Hymn was sung at the monument dedication on July 4, 1837. Emerson was in Plymouth that day. The poem was printed for the occasion but did not appear in a book until the publication of Emerson’s Poems (Boston: James Munroe and Company, 1847), 250-51. [↩]

- The woodcut “Fight at Concord Bridge” by C. N. Parmelee, takes up about one-fifth of a page in John Frost, A History of the United States; for the use of schools and academies (Philadelphia: Edward C. Biddle, 1836), 205. [↩]

- John Frost, The Pictorial History of the United States of America, 4 vols. (Philadelphia: Benjamin Walker, 1844), 165. The woodcut “Affair at Lexington,” by William Croome is on p. 166. Frost’s description of the clash at Lexington in his Pictorial History was drawn from Abiel Holmes, American Annals; or a chronological history of America from its discovery in MCCCCXCII to MDCCCVI (2 vols., Cambridge: Printed and Sold by W. Hilliard, 1805), which reports that following Major Pitcairn’s order to the militia to lay down its arms and disperse: “The sturdy yeomanry not instantly obeying the order, he advanced nearer; fired his pistol; flourished his sword, and ordered his soldiers to fire. A discharge of arms from the British troops, with a huzza, immediately succeeded; several of the provincials fell; and the rest dispersed. The firing continued after the dispersion, and the fugitives stopped and returned the fire.” Holmes was one of the first authors to credit the Lexington militia with firing on the British. (1: 325-26). [↩]

- Chappel’s originals commissioned for Spencer’s History of the United States became the property of the publisher, Johnson, Fry & Company, and were subsequently dispersed to private owners. Some have since been acquired by collections accessible to the public, among them Chappel’s painting of the Battle of Long Island, which is owned by the Brooklyn Historical Society. Others have come on the market from time to time and were acquired by private parties. Chappel’s The Battle of Lexington had recently been sold by the G. W. Einstein Company, a commercial art gallery, to a private buyer, when it was displayed on loan in a traveling exhibition organized by the Brandywine Museum of Art in 1992. See Barbara Mitnick and David Meschutt, The Portraits and History Paintings of Alonzo Chappel (Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania: Brandywine River Museum, 1992), 79. [↩]

- Jesse Ames Spencer, History of the United States (3 vols., New York: Johnson, Fry and Company, 1858), 1:336. The engraving of Chappel’s The Battle of Lexington is on the unnumbered facing page. The second edition of Spencer’s History, with a fourth volume, was published in 1866. [↩]

- A copy of the membership certificate is in the Scottish Rite Masonic Museum & Library, Lexington, Massachusetts. The date March 20, 1860, on the certificate is the date the Lexington Monument Association was established, not the publication date nor the date the certificate was filled out with the name of the donor, Augustus Child. The publication information at the lower right corner of the certificate reads “Engd. and Printd. by Smith & Knight, Boston 1861″; Charles Hudson, History of the Town of Lexington (Boston: Wiggin & Lunt, 1868). [↩]

- James F. O’Gorman, Accomplished in All Departments of Art: Hammatt Billings of Boston, 1818-1874 (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1998), 36-38, 47-48, 194-95. [↩]

- The Trial of Theodore Parker, for the “Misdemeanor” of a Speech in Faneuil Hall against Kidnapping, before the Circuit Court of the United States, at Boston, April 3, 1855 (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1864), 220 (an earlier edition of this work was privately printed for Parker in 1855). On September 10, 1858, Theodore Parker wrote to George Bancroft, thanking the historian for his new book on the Revolution, giving his grandfather’s words as “Don’t fire unless fired upon; but if they mean to have a war, let it begin here!” The letter is printed in John Weiss, Life and Correspondence of Theodore Parker (2 vols., London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts and Green, 1863), 1: 11-12. [↩]

- In his narrative of the expedition, British Ensign Jeremy Lister of the light infantry company of the 10th Foot wrote: “We had but one man wounded of our company in the leg his name was Johnson.” There was no man named Johnson in Lister’s company on April 19, 1775, but on April 24 a Private Thomas Johnston was formally transferred from another company of the 10th Foot to the light infantry. He may have volunteered to serve with the light company on the Concord expedition. Johnston was mortally wounded at Bunker Hill and died on June 23. See David Hackett Fischer, Paul Revere’s Ride (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 297, 403, note 47. [↩]

- “Concord and Lexington,” Harper’s Weekly, vol. 13, no. 643 (April 24, 1869), 260. [↩]

- Frank Wellington’s engraving of Pyle’s Lexington Green first appeared with Thomas Wentworth Higginson, “The Dawning of Independence,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine (October 1883), 731-44, at p. 734. The article appeared as a chapter in Higginson’s A Larger History of the United States of America, to the close of President Jackson’s administration (New York: Harper & Brothers., 1885) with Lexington Green reproduced on p. 246. The same engraving appeared (cropped on the left and right) in Higginson’s History of the United States (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1905), facing p. 236. [↩]

- A print of Hammatt Billing’s Battle of Lexington struck off thereafter includes a little engraving of the boulder on the border. [↩]

- Pitcairn noted that the leading elements of the British column reached the village of Lexington at 5 am. At the longitude of Lexington sunrise on April 19 occurs at 5:22 am apparent local solar time, by which contemporaries kept time. Nathaniel Low of Boston’s An Astronomical Diary, or Almanack for Year of Christian Era, 1775) reports sunrise on April 19 at 5:19 am. In Eastern Standard Time sunrise at Lexington is about 25 minutes earlier. See “Methods of Timekeeping, 1775,” Appendix N, David Hackett Fischer, Paul Revere’s Ride, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 318. Assuming Pitcairn was correct, the firing took place in half-light at or just before sunrise. [↩]

- For the formation of the Lexington Historical Society and the purchase of the Sandham painting for $4,000, see Charles Hudson, History of the Town of Lexington . . . revised and continued to 1912 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1913), 488-89, and Proceedings of the Lexington Historical Society (Lexington: Published by the Historical Society, 1890), viii-ix, xiii-xiv. The Society unveiled the painting on August 11, 1886. A collotype (a print from a plate prepared from a photographic transparency) of The Dawn of Liberty was published by the Neogravure Co. of Boston in 1911 (prints are in the Library of Congress and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). A miniature engraving of The Dawn of Liberty appeared on the two-cent postage stamp issued to commemorate the 150th anniversary of Lexington and Concord in 1925. A color print of a detail of the painting appeared on the ten-cent stamp issued to commemorate the 200th anniversary of Lexington and Concord in 1975. It bears the misleading title “Lexington and Concord 1775 by Sandham.”

Albion Harris Bicknell of nearby Malden painted the battle about the same time Sandham painted The Dawn of Liberty. This sepia reproductive photograph of the painting is in the Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library, to which the library has assigned the date 1890. [↩]

Albion Harris Bicknell of nearby Malden painted the battle about the same time Sandham painted The Dawn of Liberty. This sepia reproductive photograph of the painting is in the Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library, to which the library has assigned the date 1890. [↩] - An engraving of The Fight on Lexington Common appeared as an illustration to an installment of “The Story of the Revolution” by Lodge in Scribner’s Magazine, January 1898. The engraving was published as an illustration in Lodge’s The Story of the Revolution (2 vols., New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1898), 1: 37. [↩]

- The painting was displayed at the Royal Academy of Art in 1910 and reproduced in a color lithograph in vol. 5 of Earl A. Barker, et al., Cassell’s History of the British People (7 vols., London: The Waverly Book Company, 1910. [↩]