The battlefield of Manassas is so close to Washington, D.C., that in the summer of 1861 spectators rode out from the city to watch the Union army attack the Confederate army on Bull Run, expecting victory. “They came in all manner of ways,” an artillery officer remembered, “some in stylish carriages, others in city hacks, and still others in buggies, on horseback and even on foot. Apparently everything in the shape of vehicles in and around Washington had been pressed into service for the occasion.” Most of them got no closer to the battlefield than the high ground around Centreville, five miles away, from which they could see the smoke of battle rising beyond Bull Run. A few hours later they were swept up in the disorganized mass of Union soldiers fleeing in defeat.

They were the first of millions of Americans drawn to the battlefield of Manassas. In 2022 more than 500,000 people visited Manassas National Battlefield Park to learn about two of the most important battles of the Civil War — the first fought on July 21, 1861, and the second on August 28-30, 1862. Few of our battlefields have such a remarkable capacity for instruction and enjoyment within easy reach of millions of Americans. Manassas battlefield is a national treasure to be cherished and carefully preserved.

Yet over the last seventy years Manassas battlefield has been threatened repeatedly by highway construction and suburban sprawl, each episode more menacing than the one before. Each time men and women of good will have successfully defended the battlefield. Today the battlefield faces another threat — vastly larger in scale than anything that has been proposed in the past and potentially more destructive.

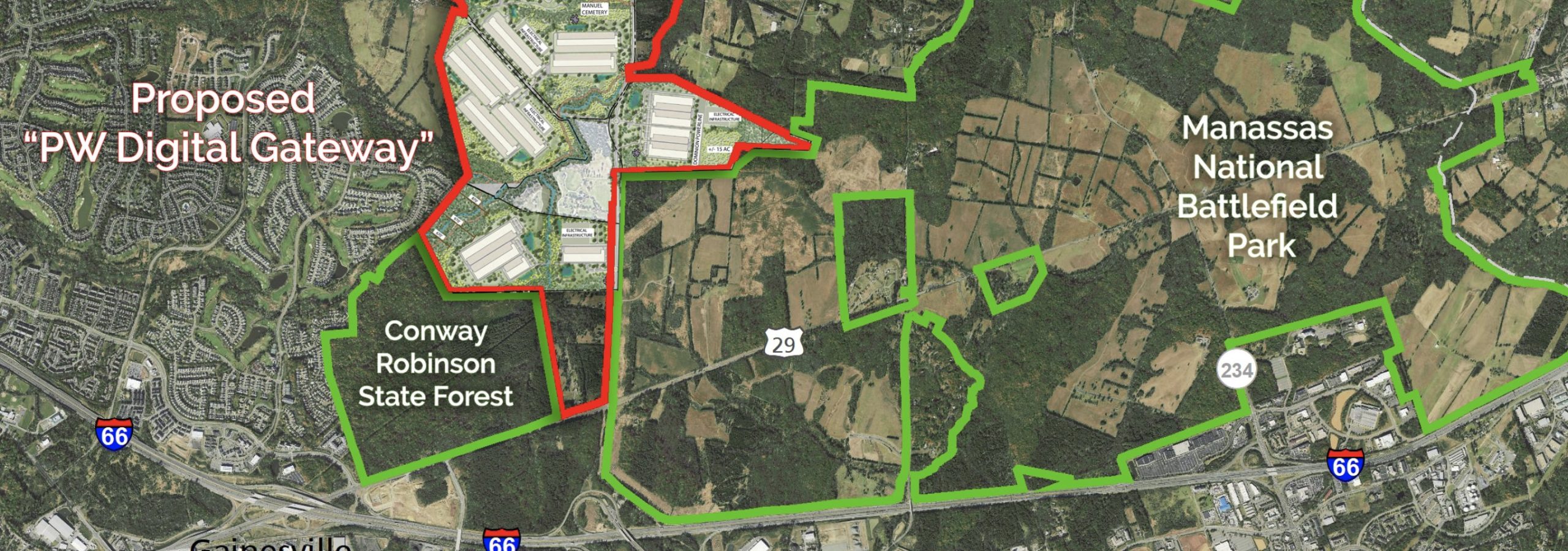

This threat looms over the last large unprotected part of the battlefield — land where the right flank of the Confederate army held its ground in the Second Battle of Manassas and just behind the line Stonewall Jackson’s men fought to hold through two days of fighting. This property along Pageland Lane on the west side of the battlefield was long zoned for agricultural use, perfectly suited to provide a buffer for the park. Then on December 13, 2023, a lame-duck session of the Prince William County Board of Supervisors voted to rezone 2,100 acres of agricultural land to facilitate the construction of an industrial complex to house the world’s largest internet data storage and processing center, a sprawling complex of dozens of eight to ten story buildings with as much as twenty-seven million square feet of floor space, four time as much as the Pentagon, the world’s largest office building. That’s more floor space than 150 Wal-Mart Supercenters.

Fifty years ago, when a developer proposed to build an amusement park on the battlefield of Second Manassas, historian Bruce Catton explained the profound importance of our battlefield parks. “They are not obtrusive tourist traps,” he wrote, “clamoring for attention, baited by the arts of honky-tonk; they are just quiet bits of land preserving the memory of scenes where heroic men of the north and south displayed a bravery, a devotion and a capacity for self-sacrifice that still have the power to move us.”

That power depends on their remaining “quiet bits of land” providing opportunities for reflection and thoughtful study. The data center development — dubbed the “Prince William Digital Gateway” — will make such reflection difficult, perhaps impossible, on parts of Manassas battlefield. It’s hard to imagine young men risking their lives in patriotic strife while listening to the whir of industrial machinery in the shadow of dozens of massive windowless buildings.

Men and women have worked for decades to preserve Manassas battlefield. The federal government, the Commonwealth of Virginia, and ordinary Americans, working through private organizations like the American Battlefield Trust, have invested hundreds of millions of dollars and many years of effort to preserve, interpret, and promote the battlefield. That investment should not be squandered. The integrity of the park they have created should not be compromised for the financial benefit of industrial data center operators. The data center can be built elsewhere. It should be built elsewhere. And if good sense prevails, it will be built elsewhere.

♦ ♦ ♦

Confederate armies won both battles of Manassas, which goes a long way toward explaining why Manassas was one of the last of the major Civil War battlefield parks to be established. The federal government created battlefield parks at Shiloh, Gettysburg, Vicksburg, Antietam, Chickamauga, and Chattanooga in the 1890s. With the exception of Chickamauga, a Confederate victory but also a prelude to Chattanooga, these were all Union victories. Creating a park at Manassas, the scene of two stunning Union defeats, held far less appeal to northern congressmen. National parks were established at Kennesaw Mountain, Petersburg, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, Stones River, and Fort Donelson before the federal government made an effort to preserve Manassas battlefield. If the federal government had made a commitment to preserve Manassas battlefield in the 1890s, it might have quickly acquired most of the battlefield as it did at Shiloh.

The Department of the Interior, acting under authority granted by the Historic Sites Act of 1935, created Manassas National Battlefield Park in 1940. It was originally only 1,600 acres and centered on Henry House Hill, scene of the decisive phase of the first battle. Much of the battlefield of 1861 and most of the battlefield of 1862 lay outside the park, but the land was not then threatened by development. The original boundaries of the park reflected the assumption that adjacent land would remain rural and that there was no need to acquire all of the battlefield in order to protect it. No one imagined the need to create a buffer around the battlefield restricted to agricultural use. The idea that it would ever be attractive for industrial development was scarcely imaginable.

The Stone House — built in 1848 as a toll house on the Warrenton and Alexandria Turnpike — survived both battles. This photograph was taken from the northern foot of Henry House Hill looking north around the time the national park was established. The National Park Service acquired the Stone House in 1949 and subsequently removed the various sheds and other buildings that had accumulated on the site, returning it to its wartime appearance. Interstate 66, according to the original plan, would have been cut across the battlefield at this point. Courtesy National Park Service

Highway construction posed the first serious threat to the battlefield. The original proposal for I-66, presented in 1957, called for the construction of a four-lane limited access highway through the heart of the battlefield. The park superintendent and his allies managed to avert that disaster. The highway was built a mile south of the park visitor center, well away from the battlefield. In 1969 the same superintendent managed to rally support to fend off a proposal to use part of the battlefield as an annex to Arlington National Cemetery.

In 1973 the Marriott Corporation proposed to build a “Great America” amusement park on 513 acres on the west side of the battlefield — land on the south side of the Warrenton Turnpike (modern Route 29) that had figured prominently in the Second Battle of Manassas but which lay outside the park boundaries. The property, from which the Army of Northern Virginia launched its decisive attack, included the site of General Lee’s headquarters. The Prince William County supervisors were willing — eager in fact — to smooth the way for Marriott’s amusement park and convened a meeting that voted to rezone the land without providing public notice of the meeting in the manner prescribed by state law. Public opposition, coupled with the difficulty securing an interchange on I-66 and the need for an environmental impact statement stalled the development, which Marriott had planned to open in time for the 1976 bicentennial. The company put its plans on hold and invested its time and money elsewhere.

The controversy stirred an effort to expand the boundaries of the park. It took years of legislative maneuvering to secure congressional support and more years to purchase the land, but by 1985 the park included Brawner’s Farm, where the Second Battle of Manassas began on August 28, 1862.

The expanded park did not include the Marriott tract, which the county supervisors still hoped to see developed. Although Marriott had abandoned its plans for an amusement park, the eventual development of the property still posed a threat to the integrity of the battlefield. In 1985 National Park Service Director William Mott warned that large-scale development just beyond park boundaries could “destroy the historical atmosphere of the parks just as surely as adverse development within their boundaries.” To protect against these intrusions, he said, parks depend on zoning and building permit systems established and enforced by local governments to maintain the viewsheds outside their boundaries.

That same year Marriott sold its property through a third party to William T. Hazel, a Northern Virginia developer. Shortly thereafter Hazel and his partner Milton Peterson announced plans for a mixed used development, which they called the William Center, with a combination of residential and office buildings. The county supervisors, anxious for the tax revenue, smoothed the way. But when the developers added a massive shopping mall to the plan in 1988, preservation advocates turned saving Manassas battlefield into a national cause.

The prospect of a shopping mall — a symbol of commercialism and suburban sprawl — on the Manassas battlefield inspired outrage across the country. With the necessary zoning and permits secured from the county and in no mood to negotiate, Hazel sent in the bulldozers to begin developing the site, a miscalculation that only stiffened resistance. The controversy ended when Congress passed a bill taking the property, which President Reagan signed. Congress added the land to the park and federal government paid Hazel/Peterson over $130 million.

This was the most recent large addition to the park. At that point the park embraced slightly over 5,000 acres. Pockets of important battlefield land inside the authorized boundaries of the park remained in private hands, as did land around the boundaries where the armies maneuvered, posted artillery, operated field hospitals, and buried some of their dead.

The American Battlefield Trust — the national battlefield preservation organization shaped by the preservation campaigns of the 1980s — has acquired some of these tracts, pursuing its patient strategy of acquiring battlefield land at fair market value from willing sellers with a combination of grant funds and private donations from its members. Those donors know that the land will be turned over the National Park Service and preserved and interpreted for visitors in perpetuity — a powerful incentive to support the organization. But even the American Battlefield Trust, for all its energy, fundraising ability, and negotiating skill, cannot afford to buy out the data center developers.

The proposed site of the industrial data center lies along rural Pageland Lane. Roads are paved and a few more houses have been built, both otherwise the landscape has changed little since the Civil War. The Bull Run Mountains, the eastern foothills of the Appalachians, are in the western distance. Industrial data center development would destroy the rural character of this area. Courtesy Piedmont Environmental Council

♦ ♦ ♦

Until recently many of us didn’t give much thought to the fact that the internet requires enormous infrastructure to work, most of it housed in massive windowless buildings up to one hundred feet tall clustered in industrial parks, many covering thousands of acres.

The proposed “Prince William Digital Gateway” would be one of the largest data center complexes in the world. Massive buildings in the southern part of the site would occupy part of the battlefield of Second Manassas and would be visible from the western side of the park. Courtesy American Battlefield Trust

These data centers consume enormous amounts of electricity and water to maintain stable temperature and humidity and operate thousands of servers and other equipment. They include backup generators powered by large diesel engines with sufficient capacity to operate for days when power from the grid is interrupted. The proposed data center is estimated to require three gigawatts of electricity, five times more than all the homes in Prince William County. Data centers now consume one-fifth of the electricity used in Virginia, which is home to one-third of the world’s large-scale data centers. An astonishing 70% of global internet traffic passes through Loudoun County alone, much of it moving through data centers clustered near Dulles Airport.

Dulles is just twelve miles north of Manassas National Battlefield Park, but because it lies in Loudoun County the tax revenue generated by those data centers benefits the state and Loudoun County government. Prince William County supervisors want a share of data center tax revenue for their county and welcomed the proposal from two large data center operators, QTS and Compass Datacenters, Inc., to build right up to the National Park Service property line.

Industrial zoning districts (blue) and a variety of business (red) and mixed use districts (brown) dominate the area south of Interstate 66 south of the park in this 2023 Prince William County Zoning District Map. Agricultural (A-1) zoning provided a rural buffer on the west and north boundary of the park where major fighting took place in the Second Battle of Manassas. Courtesy Prince William County Government

Increasing the tax base often crowds other priorities out of the minds of local elected officials, especially in a jurisdiction like Prince William County where the population and thus the demand for roads, schools, and county services is growing quickly. Instead of serving the people who live in their jurisdiction by working to maintain a good quality of life in the county, this financial pressure turns them into tools of outside developers and makes them more concerned about providing roads, schools, and services to people who don’t live in the county yet instead of the people who live there now and elected them.

Data centers are to the 2020s what shopping malls were to the 1980s — tax revenue generators for county governments. When developers and their various clients in business and organized labor contribute to getting them elected, county officials regard them, openly or not, as valuable partners. And because most county officials are elected for terms of three or four years and rarely serve more than two or three terms, they aren’t particularly concerned about the long term consequences of their decisions or are short sighted and believe that today’s development will have lasting benefits. The suburban landscape is littered with decaying shopping strips occupied by pawn shops and tattoo parlors and vacant malls where weeds grow through cracks in empty parking lots as a result.

Data centers serve technology that didn’t exist thirty years ago and will be obsolete thirty years from now. Today’s data centers are tomorrow’s abandoned shopping malls, except they will be considerably more expensive to demolish. Authorizing construction of a data center when it diminishes the integrity of a national park — and the overwhelming view is that it will — is irresponsible.

A May 2023 poll by the National Parks Conservation Association found eighty-six percent of Northern Virginia residents — Republicans, Democrats, and Independents in equal measure — want to prohibit data centers within one mile of national parks and historic sites. Most residents of the area around the tract oppose industrial development next to Manassas National Battlefield Park.

So do regional and national organizations representing millions of people, including the American Battlefield Trust, the Manassas Battlefield Trust, the National Parks Conservation Association, the Piedmont Environmental Council, the Sierra Club, Journey Through Hallowed Ground, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, the Coalition for Smarter Growth, and the Prince William Conservation Alliance (the links above are to statements by these organizations about the propose development). Ken Burns, whose documentaries on the Civil War and on our national parks have been enjoyed by millions of viewers, wrote to the the county supervisors: “I fear the devastating impact the development of up to 2,133 acres of data centers will have on this hallowed ground.” Prince William County’s professional planners oppose the rezoning. So, too, do the two county supervisors who represent the people who live in the districts where the industrial development is proposed.

Kristopher Butcher, superintendent of Manassas Battlefield National Battlefield Park, and several of his predecessors have expressed grave reservations about the development, warning that it would compromise the integrity of the battlefield and diminish the experience of the hundreds of thousands of visitors who come to the national park every year. In December 2021 Superintendent Brandon Bies called the data center proposal “the single greatest threat to Manassas National Battlefield Park in nearly three decades.”

With so many opponents, who is in favor of industrial data center development on the edge of a national park?

The people who own the land stand to benefit. As agricultural land their property is worth only a fraction of the value added by industrial zoning. Some of them have posted signs on their land with messages like “data centers = jobs in PWC,” which is true enough, “data centers = better schools,” which is debatable, and “data centers = more money for parks,” which is misleading. The county might dedicate some new revenue to parks, but none of it would go to Manassas National Battlefield Park. Any public benefits the development might generate adjacent to the battlefield park it would generate in another location.

The industrial developers benefit, of course. They have calculated that building adjacent to the national park, where there are willing sellers and a high voltage transmission line, will provide a handsome return on their investment. The International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers likes the idea. The data center would employ lots of its members, so it donated $130,000 to the five Democrats who made up the board majority in 2023. Since taking office in 2020, that majority, led by Chairman Ann Wheeler, has never voted against rezoning land to facilitate the building and operation of massive industrial data centers.

The developers first proposed the “Prince William Digital Gateway” in 2021 — initially seeking support for an 800 acre site. Like Hazel/Peterson’s William Center proposal of the 1980s it grew in scope until by 2023 the proposed development exceeded 2,000 acres. By then the supervisors supporting the development had to move fast to rezone the land because their majority was vanishing. They violated regulations regarding public notice to bring the rezoning to a vote before Wheeler went out of office on January 1. She was defeated last June in her bid for the Democratic nomination, largely due to her unreserved support for data center developers, and wasn’t on the ballot in November.

The southern part of the proposed data center development would be wedged between a residential area on the west, a state forest on the southwest, and Manassas National Battlefield Park on the south and east. Courtesy Piedmont Environmental Council

Forcing a vote on the massive industrial development overlooking Manassas National Battlefield Park in December while she had a narrow, lame-duck majority was Ann Wheeler’s final act in office. She and her colleagues voted along party lines. Four Democrats voted for rezoning. Three Republicans voted against it. One Democrat abstained after his compromise motion to approve rezoning on two-thirds of the land failed.

On her way out, Wheeler did nothing to disguise her contempt for park defenders. The data center developers are not going anywhere, she said, “and these thirty groups that oppose them are all conservation groups that oppose all development. That’s what they do.”

None of that is true. The developers will go elsewhere if they don’t secure the necessary rezoning, and there are available alternative sites in Virginia with access to reliable low-cost electricity and the technical workers they need. And despite Wheeler’s jab, most preservation groups are pragmatic about development. The region has “ample industrial land to build data centers,” says Kyle Hart, Mid-Atlantic Program Manager for the National Parks Conservation Association.

David Duncan, president of the American Battlefield Trust, candidly acknowledges the need for data centers while arguing that they don’t belong on the edge of a national park. “It is important to remember that development and preservation need not be mutually exclusive,” the Trust says. “Thoughtful policy and land-use decisions can result in thriving communities that embrace technology and economic growth while respecting the unique historic and environmental resources that cannot be moved.” So far thoughtfulness has not prevailed.

Defenders of Manassas National Battlefield Park have filed a lawsuit to overturn the rezoning decision and given the irregularities involved they have a compelling case to make in court. They are working hard to preserve the battlefield, as they have done for eighty years, but their success is far from certain.

♦ ♦ ♦

The “Prince William Digital Gateway,” if built, would loom over the west side of Manassas National Battlefield Park. The development would diminish the integrity of the whole battlefield, most of all Brawner’s Farm, where the Second Battle of Manassas began on August 28, 1862. It would compromise the experience of visitors and dishonor the brave men who fought there. Their story is part of our story — the common heritage of all Americans.

In 1862 Brawner’s Farm was indistinguishable from the many simple places — peach orchards and cornfields — made terrible by the Civil War. John Brawner paid the widowed Augusta Douglass $150 a year plus two-thirds of each harvest to rent the farm and humble frame house known locally as Bachelor’s Hall. Brawner, sixty-four, lived there with his wife and three daughters. They fled when the fighting started.

Late on August 26, Confederate troops under Stonewall Jackson, having stolen a march on John Pope’s Federal Army of Virginia, captured Pope’s supplies at Manassas, including, a Louisiana chaplain wrote, “some million dollars worth of biscuit, cheese, ham, bacon, pork, coffee, sugar, tea, fruit, brandy, wine, whiskey, [and] oysters.” The hungry soldiers ate their fill, took what they could carry, and burned the rest. They withdrew a few miles to the north to a strong defensive position near the graded cut of an unfinished railroad that ran southwest from Sudley Ford on Bull Run toward the Warrenton Turnpike.

Pope’s army, once Pope realized that a large part of Lee’s army had gotten between his army and Washington, fell back from the Rappahannock and marched east up the Warrenton Turnpike toward Bull Run, intent on defeating Jackson before the rest of Lee’s army arrived.

When they reached Brawner’s Farm on the turnpike Union troops were less than half a mile from Jackson’s position near the railroad cut. Jackson might have gone undetected, but this suited neither Jackson’s aggressive nature nor the larger strategic situation. The Confederates needed to defeat Pope’s army before it joined with McClellan’s Army of the Potomac, which was being transferred from the Virginia Peninsula to Washington by water. Jackson, though outnumbered, ordered an attack on the passing Union column.

Men of the 19th Indiana fought Virginians of the Stonewall Brigade at this spot just south of the Brawner house. The scrubby trees at right had grown up since the war. Historic American Building Survey Photograph, Library of Congress

The battle began near sunset. Under Confederate artillery fire John Gibbon’s brigade of Indiana and Wisconsin men, thereafter known as the Iron Brigade, moved off the exposed turnpike into the woods on the Brawner Farm. Among them was a twenty-four year-old corporal named Joshua Jones, a farmhand who had left his wife, Celia, and two-year-old son to serve in the 19th Indiana.

“Often,” he wrote to Celia, “do I think of the hapy days when I Could Sit down to Breakfast with you and See the little boy Stick his head up in the Bed and laugh while we was eating and talking to each other as hapy as too kings . . . my dear I can See now that we lived as pleasant a life as any too on earth,” adding “you know how well I used to like to have holt of your little hand I can almost feel it now.” He told her that “If I live I will be at home when the war is over, and if it falls to my lot to fall in Battle it will be in defence of my Country.”

Artist Edwin Forbes made this sketch of the battle at Brawner’s Farm from high ground, now called Battery Heights, near the Warrenton Turnpike A Union battery is firing over the heads of Gibbon’s brigade. The Confederate Stonewall Brigade is arrayed along the tree line (number 3 on the sketch). Morgan Collection of Civil War Drawings, Library of Congress

Moving north out of the woods Gibbon’s brigade ran into the advancing Stonewall Brigade near the Brawner House. The Stonewall Brigade, the old command of General Jackson, had been winnowed by a year of war to a mere 635 men, but what was left was choice. Abner Doubleday’s brigade, New Yorkers and Pennsylvanians, went into battle on Gibbon’s right, where they faced Confederate brigades under Alexander Lawton and Isaac Trimble. Neither side maneuvered for advantage. Virginia and Indiana men stood facing one another in Brawner’s farmyard, seventy to eighty yards apart, and shot at one another for an hour and a half.

The Civil War was punctuated by moments like this, when warfare was reduced to its essential elements — no one thinking about the cause that had brought them to this place, their minds reduced to the immediate business of loading, firing, reloading, and firing again. From a distance a federal soldier thought it sounded like “hailstones upon an empty barn.”

The smoke filled the still summer air and as evening came on the two lines could be traced by the bright flashes of musket fire. Sometime the firing would slacken a little,” a New Yorker wrote, “but then came a wild cheer and a yell and the rattle of musketry would become louder and more fierce than ever.”

Cornelius Wheeler, a former teacher, was a corporal in the 2nd Wisconsin Infantry at Brawner’s Farm. His regiment lost 276 men out of 430 men engaged at Second Manassas. Wisconsin Historical Society

Joshua Jones found himself in the thickest part of the fight, facing the Stonewall Brigade across Brawner’s farmyard. The man to his left and the two men on his right fell. The regimental colors were shot to pieces. “Jacob Miller was wounded & fell at my feet & his gun hit me on the Shoulder as he fell,” he wrote. “I got one ball hole in my hat & one through the left side of my Coat.” Twice the Stonewall Brigade tried to charge. Each time the Indiana men drove them back. They were, a private wrote, “like two dogs fighting.”

When darkness brought the shooting to an end, the two sides had scarcely moved. The Confederates had suffered more than 1,250 casualties. including Richard Ewell, the division commander, who was among the wounded and dying men left on the battlefield as night fell. The Union army had lost over 1,000 men — over 700 of them in Gibbon’s brigade alone. The 19th Indiana counted 229 dead, wounded, or missing out of 423 men engaged.

“As the daylight came on the next morning,” Gibbon’s aide Frank Haskell wrote, “none of us could look on our thinned ranks, so full the night before, now so shattered, without tears. And the faces of those brave boys as the morning sun disclosed them, no pen can describe. They men were cheerful, quiet, and orderly. The dust and blackness of battle were upon their clothes, and in their hair, and on their skin . . . I could not look upon them without tears, and could have hugged the necks of them all.”

James Buchanan McCutchan was a private in the the Stonewall Brigade, which went into battle at Brawner’s Farm with 635 men. It lost more than 200 men in the battle, half of them from McCutchan’s 5th Virginia Regiment. Library of Congress

The Union troops took up positions east of Brawner’s Farm and the Confederates fell back to the railroad cut. They had stopped Pope’s march and brought on a larger battle Lee’s army needed to win — one Pope in his vanity thought he could win, adding to his laurels before McClellan’s larger army arrived. On August 29 Pope assaulted Jackson’s troops in the railroad cut as the rest of Lee’s army, under James Longstreet, following Pope from the Rappahannock, assembled astride the Warrenton Turnpike with its left at Brawner’s Farm.

Pope renewed his assault on August 30, confident of victory. Confederate artillery massed on high ground behind Jackson’s infantry (and less than 500 feet from a proposed data center building on the park boundary). Running out of ammunition some of Jackson’s men were reduced to throwing rocks at their attackers, but at the critical moment Longstreet attacked Pope’s exposed left flank and drove the Union army toward Bull Run. Gibbon’s shattered brigade, which had been held in reserve, suddenly found itself in the rear guard of Pope’s army and slowed Longstreet just enough for most of Pope’s army to escape. Gibbon’s brigade was the last to cross Bull Run. Engineers destroyed the bridge behind them. The rout was complete.

The Union rear guard, including the survivors of Gibbon’s brigade, held Longstreet’s charging Confederates off long enough for Pope’s beaten army to escape across Bull Run. Artist Edwin Forbes drew this final sketch of the battle late on the afternoon of August 30. Morgan Collection of Civil War Drawings, Library of Congress

Somehow Joshua Jones survived it all, though he admitted to Celia that during the battle “I feared I would End my days.” He told her not to worry — that the regiment would spend the fall safe in Washington — but three weeks after the battle at Brawner’s Farm he was wounded at Antietam. Doctor’s amputated his leg but were unable to save his life. He died a few days later.

Preservationists know we cannot preserve everything. The American people have already lost most of the major battlefields of our Revolutionary War. The battlefields of Bunker Hill, Brooklyn, Trenton, Charleston, and Savannah lie under city streets. Urban growth and suburban sprawl have claimed the Civil War battlefields of Atlanta and important parts of the battlefields of Fredericksburg, Franklin, and Nashville. Salem Church and Chantilly are buried under shopping centers and residential subdivisions. We have to make choices about what we want to preserve. The American people have chosen to preserve Manassas battlefield.

Manassas National Battlefield Park is, above all else, a quiet memorial. It stirs thoughts of the loved and lost, of courage that overcomes fear, and of devotion to country that calls for great sacrifice. Its stories are our stories. Its heroes are our heroes and its tragedies are our tragedies. We should do nothing to diminish it, because that courage and sacrifice have shaped our national identity.

If you are moved to do something to address the threat to the Manassas battlefield and other great historic places, we recommend you consider supporting the advocacy program of the American Battlefield Trust.

The American Battlefield Trust is a proven leader in the field with an extraordinary record of success, a reputation for crafting win-win solutions where possible, and for fighting fiercely, when necessary.

Photo Credit: The photograph at the head of this article, “Henry House — Manassas Battlefield” is by Gregg Obst (GreggObst.com).