When the First Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia’s Carpenters’ Hall on September 5, 1774, Patrick Henry called on the delegates to set aside their provincial concerns and embrace a common purpose and a common destiny. “The distinction between Virginians, Pennsylvanians, New Yorkers and New Englanders,” he said, “are no more. I am not a Virginian, but an American.”

Saying it out loud did not make it true. There remained enormous differences between Virginians and Pennsylvanians and even more differences between New Englanders and Carolinians. But saying it raised the possibility that one day it might be true — that the peoples of British North America might somehow form a single nation.

Neither Henry nor anyone else understood how this might happen, but they had come together to deal with common concerns, and every day they worked together the closer together they would be drawn until somehow they would be more American than anything else.

This was as true of ordinary Americans. Their shared labors, shared ideals, and the shared experiences of thousands of soldiers and citizens over a war that lasted eight years created an American national identity. Without erasing local and regional attachments, the Revolution made Americans “one people,” in the words of the Declaration of Independence, bound by common ideals and a common history of resistance, suffering, failure, and success.

“At the close of that struggle,” Abraham Lincoln wrote in 1837, “nearly every adult male had been a participator in some of its scenes. The consequence was, that of those scenes, in the form of a husband, a father, a son, or a brother, a living history was to be found in every family — a history bearing the indubitable testimonies to its own authenticity in the limbs mangled, in the scars of wounds received in the midst of the very scenes related; a history too that could be read and understood alike by all, the wise and the ignorant, the learned and the unlearned.” Together they had created a new nation, unlike any that had ever existed.

Our national identity has been enriched by 250 years of shared experience. It is the basis of American patriotism, a spirit too many misunderstand and far too many malign.

Patriotism is under pressure from political extremists. Many on the left regard patriotism as a misplaced sentiment that ignores troubles in our past — a cover for racism, xenophobia, exploitation, and militarism. They argue that patriotism is a relic of an ugly past, synonymous with nationalism and corrupted by nationalism’s vices.

Nationalism, indeed, has vices, but patriotism and nationalism are different ideas. Nationalism is exclusionary. It focuses on distinctions between nations and makes a claim of inherent superiority for its own. Its roots lie, not in distant antiquity, but in the nineteenth-century European impulse to redefine statehood using race, ethnicity, language, and culture rather the monarchical subjection as organizing principles. Nationalism is preoccupied, at its most benign, with the desire for prestige, an impulse burdened with the sin of pride.

The vices of nationalism — racism, militarism, imperial ambition, and xenophobia — lie close to the surface and have shaped two centuries of bloodshed. Vladimir Putin’s fantasies of Russian ethnic superiority and destiny are only the most recent.

Blood and soil nationalism of the European sort has put down no more than shallow roots in the United States, though we are not immune to it. The United States was touched by the nationalist impulse in the nineteenth century, but it was always at odds with American idealism, which was deeply rooted in the universal humanitarian impulses of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment. In this sense the United States is not a young nation. It is, in important ways, a very old one.

A nation of immigrants from many lands and their descendants is poor soil for nationalism rooted in ethnicity. So-called white nationalism can find little in the American past, beside the Klan and other manifestations of racial hatred and cracker anxiety, in which to grow. It is a fringe movement, its alien nature apparent in its reliance on the ideas and symbols of the Nazis, who despised the United States. Its kinship is not with patriotism but with the ethnic and racial grievance movements of the left.

Thoughtful patriotism is a kind of piety, of shared respect for beneficial traditions that binds people together across time, space, and in the United States, across ethnic boundaries. It involves respect for the achievements of the past, though never ignoring failures and shortcomings. It is a solvent that dissolves class conflict by embracing the common aspirations of ordinary people.

Patriotism is an attachment to the “Land where my fathers died,” in the words of the old song. But for Americans, this has a special meaning. Our fathers have died defending our highest ideals in every part of the world. They lie in nameless graves on Tarawa and in ordered ranks beyond Belleau Wood, places they died so freedom would survive the onslaught of predatory nations intent on conquest.

This kind of patriotism must be nurtured. Parents have a role in raising thoughtfully patriotic children. Indeed if they hold their country in contempt it isn’t likely their children will learn to love and care for it.

Thoughtful patriotism can only be nurtured by exposing people to the best that our history, literature, art, and political ideas have to teach us. It can only be nurtured by cultivating respect for our finest traditions and above all the ideals that have defined us for 250 years — love of independence, liberty, equality, natural and civil rights, and responsible citizenship. Understanding and appreciation of our shared history is essential to thoughtful patriotism.

Cultivating that respect does not mean asking young people to ignore injustice, exploitation, violence, and greed in our past. Far from it, because our traditions and ideals call for continuous renewal and reform — an enterprise for which we must be armed with knowledge.

“Why should I love my country?” We should prompt every young American to ask themselves this question. By the time they graduate from high school — indeed long before — they should be able to form an answer. There may be as many answers as there are young people. In free societies people choose how to use their freedom and hence what they value most. But among the things they value most should be the country in which they enjoy that freedom.

They will only learn to cherish the country if we teach them to do it. We need to do it with pride but also with humility and modesty.

We have not forgotten how. Even today the elementary school day begins, for millions of children, with the Pledge of Allegiance. In my school days many of us were confused by the pledge, and for a few years we stumbled through it, making the sounds (“and to the republic, for Richard Stands, one naked individual . . .”) but we ultimately learned the words and the sentiments.

We thought no less of the Jehovah’s Witness boy in the class who neither stood nor said the pledge, and though it seemed odd we learned that people have different principles and in our republic dissent is fine. We did not know, at the time, that the right to dissent from this ritual had been hard won — but won — in our Supreme Court.

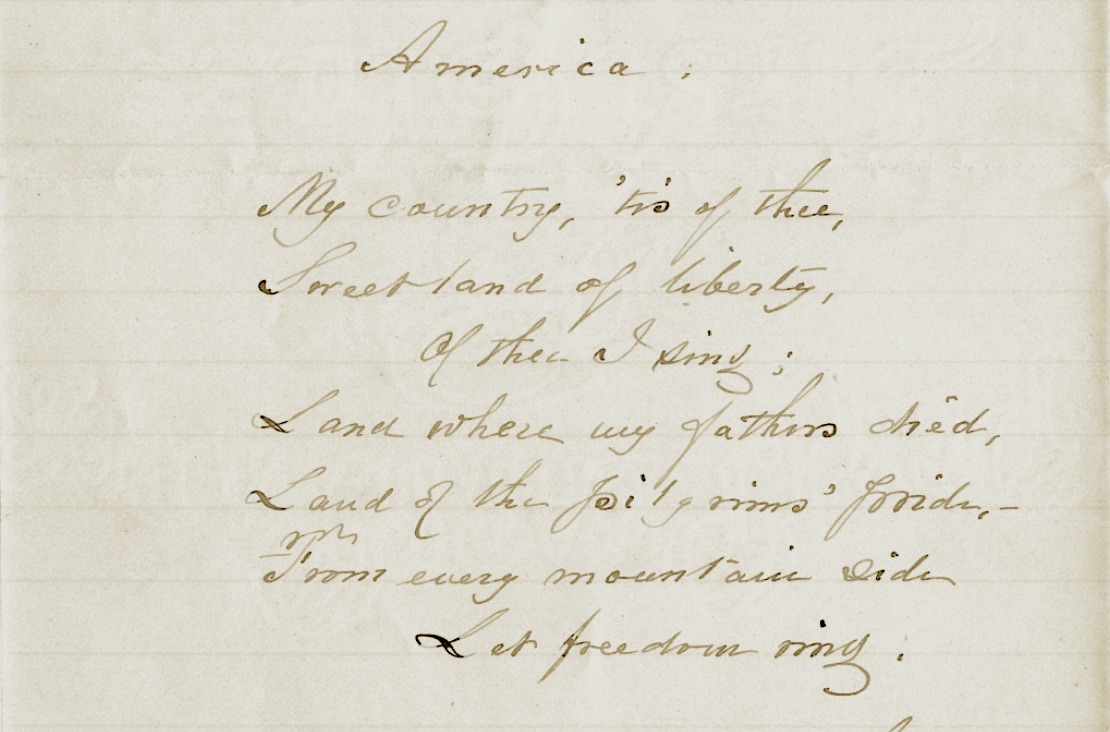

Even after public schools stopped morning prayers, we sang “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee” — the first verse, usually, with its aspiration to “Let freedom ring.” We did not know its rich past — that it had been our unofficial national song for several decades, that it had been adopted (and adapted) by abolitionists and reformers, that Marian Anderson sang it from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in 1939, and Martin Luther King recited the entire first verse in his “I Have a Dream,” speech, standing at the same spot, in 1963. No song, perhaps, is more deeply rooted in our finest traditions.

In my elementary school (a public school in what the political press calls a “blue state”) we sometimes sang the fourth verse as well: “Our father’s God, to thee, Author of liberty, to thee we sing. Long may this land be bright, with freedom’s holy light. Protect us by thy might, Great God, our King!”

The dissenters and the indifferent could mumble, stand silently, move their mouths in pretense, or sing gibberish. Most of us sang and the word of the old hymn, first sung by a children’s choir in Boston’s magnificent Park Street Church on July 4, 1831, reached across the centuries and bound us, at least in that brief moment, to Americans of a different time and place who loved their country, too.

Watch and listen as Marian Anderson performs “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee” at the Lincoln Memorial, April 9, 1939, in a newsreel from the UCLA Film & Television Archive.