The American Revolution was a peculiar sort of revolution, and not least because it was led by men we find it hard to imagine as revolutionaries. George Washington, George Mason, and John Hancock were respected and wealthy members of the gentry. They had everything to lose and apparently little to gain from revolution. They were certainly nothing like the revolutionary leaders of the last century. As a consequence we tend to underestimate the revolutionary implications of their ideas and the revolutionary consequences of their actions. We conclude that there was nothing very revolutionary about their revolution and look elsewhere for the fundamental transforming events of American history — to the Civil War, the Great Depression, and the civil rights movement.

Perhaps it is a testament to the overwhelming impact of their revolution that we can scarcely imagine what the country was like before it and conclude erroneously that their revolution was simply a colonial rebellion that shifted political power from London to America, trading one group of political grandees for another.

No conclusion could be more wrong. The American Revolution swept away the social hierarchies of the old order. It transferred sovereignty to the people at large, launching an era of increasingly democratic politics. It accelerated the economic transformation of the former colonies and led to the creation of a continental nation unlike any the world had seen.

Few Americans embodied the unique revolutionary character of the period more completely than Richard Henry Lee. He was a member of one of Virginia’s first families. The Lee name was synonymous with wealth, land ownership, and influence. Like some of his forebears, he dedicated much of his life to public service.

Unlike them, he became one of the most determined radicals of his time -— a leader of the opposition to British taxation and intrusive regulation and an early and important advocate of American independence and republican government. Lee looked for independence to reshape Virginia society — to make Virginians more self-sufficient and virtuous. Yet, like most of the patriot leaders of his generation, he did not anticipate the unintended consequences of his revolution.

Lee was born at Stratford Hall in Westmoreland County on Jan. 20, 1732 — just four weeks before George Washington was born a few miles away. Like Washington, he was a younger son and did not stand to inherit the great plantation where he was born. After education in England he built his own plantation house, Chantilly, on land he acquired from his brother.

Younger son or not, he was still a Lee, and an heir to one of Virginia’s great family traditions. Groping for a way to explain the distinctive culture of the Northern Neck, a Loyalist minister traced it to the attributes of the leading gentry families, “the Fitzhughs, the Randolphs, Washingtons, Carys, Grimeses, or Thorntons” whose “character, both of body and mind, may be traced through many generations.” Fitzhughs, he wrote, have bad eyes, and Thorntons hear poorly, while “Carters are proud and imperious; Taliaferros mean and avaricious; and Fowkeses cruel.”

“Lees,” he added, “talk well.”1

Richard Henry Lee entered the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1758, and was immediately recognized as the most talented speaker in that body. But he was, despite his name and family connections, something of an outsider.

The House was dominated by a political faction associated with the Randolphs and their network of clients and kin. House Speaker John Robinson was a part of this group. He was also the colony’s treasurer. Shortly after taking his seat, the young Lee demanded an investigation of Robinson’s management of the treasury. It was soon found that Robinson had loaned large sums to prominent families associated with his faction. Lee’s Northern Neck neighbors applauded him as a reformer, but the Robinson-Randolph faction never forgave him.

Lee reminded many of his contemporaries of a character from Roman history. He was tall and spare, with a long nose — a Roman profile — and reddish-brown hair. His manners were stiff and formal and he seemed to always be striking a pose. Even his private letters read as if he intended them for publication. But the stiffness did not diminish the admiration that others had for him. Quite the contrary — he seemed the ideal eighteenth-century gentleman. “If elegance had been personified,” Edmund Randolph wrote, “the person of Lee would have been chosen.”2

But he was unlike other gentry leaders. He owned a plantation but expressed no interest in agricultural innovations of the sort that relieved the routine boredom of farming for Washington and Jefferson. Nor did he use the pose of gentleman-farmer, as Washington did, to cloak his public life in the garb of a reluctant (and therefore deserving) hero called from the plow.

Lee called politics the “Science of fraud,” yet he never had any real profession other than politics. In addition to his oratorical skills, he excelled in cloakroom maneuvering, what eighteenth-century politicians referred to as ‘composing the business’ or working ‘out of doors.’ He angled constantly for higher and better-paid offices. He was, in fact, one of Virginia’s first professional politicians, at a time when few Virginians would have recognized politics as an occupation.3

A patrician master of the conventions of gentry politics, Lee was adept at mobilizing popular sentiment as well. But he was not a populist leader or a democrat in the modern sense. He expected the republic he worked to create would embrace the leadership of gentlemen like himself. Yet his radical politics tended to undermine gentry leadership and helped usher in a new and unexpected era of popular democratic politicians.

The American Revolution brought to the fore a new kind of popular radicalism, most closely associated with the insurgent organization forged by Boston’s Samuel Adams, who employed an array of weapons that later became a standard repertoire of urban revolutionaries — street theater, surgical rioting, strategically leaked documents, staged debates, and managed news.

Richard Henry Lee was a part of Adams’ network, and employed the same sort of tactics against the Stamp Act in the 1760s. In September 1765 he dressed his slaves up in “Wilkes costume” and marched them to Montross for a staged ceremony in which the stamp collector was hanged in effigy. Lee himself played the role of the condemned man, and read the “confession” of the accused before the dummy representing the collector was strung up.

A few months later, he used his militia to harass an uncooperative merchant, Archibald Richie of Leedstown, who vowed to use the hated tax stamps. Working with Richard Parker and Samuel Washington (the future general’s younger brother), Lee orchestrated a march on Ritchie’s home, where the mob forced the merchant to renounce the Stamp Act.

His aim, from as early as the summer of 1765, was independence. In the future, he wrote privately, Britain would learn “that America can find Arms as well as Arts” to assert its liberty, adding “If I should live to see that day I shall be happy; and pleased to say with Sydney, ‘Lord now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace.’”4

Misfortunes did not diminish his commitment to the patriot cause. In 1768 he lost the four fingers of his left hand when a gun exploded in his hands. He wrapped the maimed hand in a black cloth or wore a glove in public for the rest of his life. A few months after the accident his wife died, then the next year a hurricane wrecked his plantation.5

When the First Continental Congress met Lee greeted Samuel Adams like an old friend. They had never met but had been corresponding for years. Lee was also closely allied with Patrick Henry, Virginia’s most vocal firebrand, and was far in the lead of more cautious Virginia delegates, including Peyton Randolph and Benjamin Harrison.

Men like Randolph and Harrison were not the sort to engage in back room maneuvers but Lee was in his element. He was tied by marriage to some of the leading Philadelphia families and had cultivated contacts in New England. His speaking ability — which led more than one congressman to call him as an American Cicero — made him a major force in debate. But behind the scenes, he was even more effective in persuading his reluctant colleagues to break with Britain.6

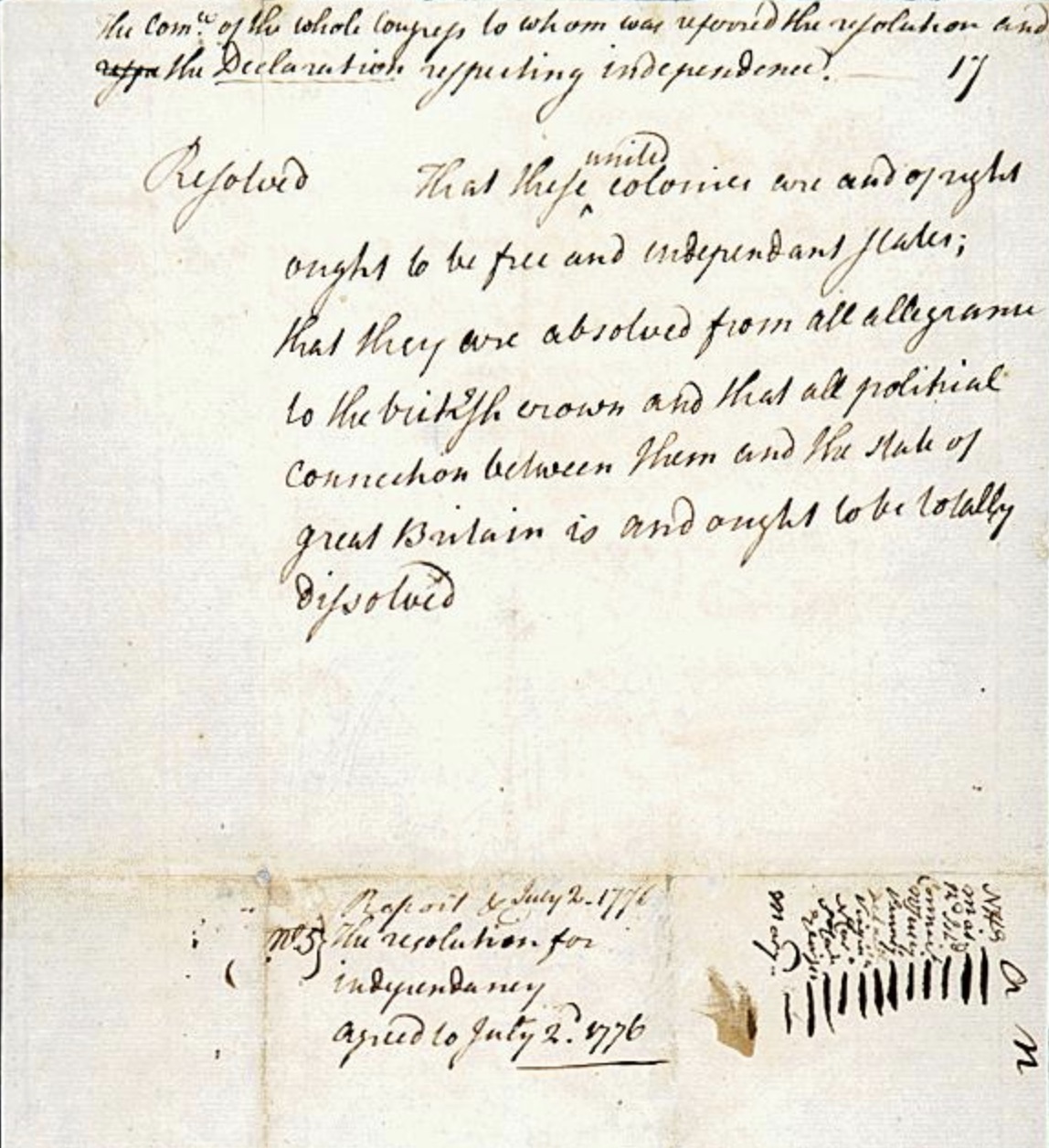

Working closely with John Adams, Lee introduced the resolutions that led to American independence. He made three different motions. We tend to remember only the first: “That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent states, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be totally dissolved.”

The casual way Charles Thomson, secretary of the Continental Congress, recorded the vote on Lee’s resolution on independence cannot disguise the transcendent importance of the event. Thomson tallied the votes of twelve states (New York abstained) at lower right, and concluded his report “agreed to July 2d 1776.” National Archives

This was bold language, simple and forthright. In time, Americans came to regard it as a prologue to the Declaration of Independence, the political backdrop for Thomas Jefferson’s eloquence. But we have it backward. The Declaration was an explanation of the measure Lee proposed. John Adams understood this when he predicted that Americans would henceforth celebrate July 2 — the day Lee’s resolutions were adopted — as the anniversary of American Independence.

The other resolutions Lee offered were nearly as important: “That it is expedient forthwith to take the most effectual measures for forming foreign Alliances,” and “That a plan of confederation be prepared and transmitted to the respective colonies for their consideration and approbation.”7

Lee was astute enough to recognize that the chance of securing military aid from France was the real selling point for the resolution on independence, that it was the only practical way to convince congressional moderates to support the idea. His efforts to establish a lasting confederation between the independent states, embodied in the Articles of Confederation, helped build the foundation for a continental republic.

Unlike some of the other congressmen, Lee relied on his small congressional salary for a living. Payment was irregular and he was often in financial distress. For a few weeks in 1777 he lived mainly on wild pigeons, which were sold for a few cents per dozen, though they “afforded but a scanty fare.”8

Lee’s revolutionary ideas were not limited to independence, foreign alliances, and a continental confederation. He expressed support for the idea of allowing women who owned property to vote, opposed secret legislative sessions, and demanded a bill of rights be attached to the Federal Constitution. These were, for him, natural consequences of the revolutionary commitment to equality.

Lee’s commitment to the principle of equality was in conflict with his dependence on enslaved people. He saw that the logic of the Revolution underscored the injustice of slavery. African-Americans, he wrote, were “fellow creatures created as ourselves, and equally entitled to liberty and freedom by the great law of nature.” Moreover, they would eventually be driven to rebellion when they “observed their masters possessed of a liberty denied to them.” Yet through most of his adult life, he realized much of his income from renting his slaves to other planters. As a member of the House of Burgesses, he advocated taxing new imports of slaves and other restrictions on the slave trade, but this may have been as much to drive up the price of his own slaves as it was a humanitarian effort. Lee recognized the inconsistency of it all, but in the end he could see no other way: “I do not see how I could in justice to my family refuse any advantages that might arise from the selling of them.”9

Richard Henry Lee was a radical revolutionary without being a democrat. He believed in popular sovereignty but he was certain that the people would be best served by deferring to gentlemen like himself. In 1788 he was elected to the U.S. Senate, where he championed a resolution to endow federal officials with aristocratic-sounding titles. It was an effort to defend the tradition of deferential politics and gentry rule that he was believed was essential for the survival of republican government.

The House of Representatives rejected the idea. A revolutionary republic established on the foundation of popular sovereignty ultimately had little use for titles or patrician leaders. The Revolution Richard Henry Lee did so much to foment and to lead ended by discarding the leadership of gentlemen revolutionaries like him in favor of a new kind of democratic politician, often common in background and lacking the classical education and aspirations that distinguished Lee and his peers. The Northern Neck of Virginia never produced another American Cicero.

Chantilly, Lee’s home in Westmoreland County, fell into ruin after his death. Archaeologists discovered the foundations in 1967. Virginia Department of Historic Resources

Lee did not live to see the Virginia that his revolution produced. In ill health, he resigned from the Senate in 1792. He died at Chantilly, his home in Westmoreland County, in 1794. The democratic culture that flowed from Lee’s revolution ensured that there would never be another leader like him.

That revolution also accelerated the process that turned the Northern Neck, one of the most important and distinctive regions in eighteenth-century British America, into an economic and political backwater. The fortunes of the great planter families continued to fade as agriculture productivity declined and capital was drawn away from the Chesapeake region toward the new states and territories to the west and into new commercial enterprises.

By the early decades of the nineteenth century, the distinctive plantation culture of the Northern Neck was gone and with it the gentry that had produced leaders like Lee. Stratford Hall’s ceilings were falling in, its fields uncultivated. A traveler found nothing left of Chantilly but a crumbling chimney. “Lee is gone, his house is in the dust, his garden a wild. . . . What a leveller is Time!”10

Notes

- Jonathan Bouchier, ed., Reminiscences of an American Loyalist, 1738-1789, Being the Autobiography of The Revd Jonathan Boucher, Rector of Annapolis in Maryland and afterwards Vicar of Epsom, Surrey, England (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1925), 61-62. [↩]

- “Edmund Randolph’s Essay on the Revolutionary History of Virginia, 1774-1782,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 43, no. 3 (July 1935), 222-23. [↩]

- Richard Henry Lee to Thomas Lee Shippen, September 21, 1791, James Curtis Ballagh, ed., The Letters of Richard Henry Lee, vol. 2: 1779-1794 (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1914), 543-44. [↩]

- Richard Henry Lee to Landon Carter, August 15, 1765, James Curtis Ballagh, ed., The Letters of Richard Henry Lee, vol. 1: 1762-1778 (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1911), 11-12. [↩]

- He called it an “unhappy wound” but did not let it stop him from attending the House of Burgesses that spring. Richard Henry Lee to an English correspondent, March 27, 1768, Ballagh, ed., Letters of Richard Henry Lee, vol. 1: 26-27. [↩]

- For comparisons of Lee and Cicero, see, e.g., Diary of John Adams, August 28, 1774, Lyman H. Butterfield, ed., The Adams Papers, vol. 2, 1771–1781, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1961), 113-14. [↩]

- Resolution of Independence Moved by R. H. Lee for the Virginia Delegation, June 7, 1776, Julian P. Boyd, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 1: 1760–1776 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1950), 298-99. [↩]

- Virginia Delegates to Congress to George Pynchon and John Bradford, October 16, 1777, Ballagh, ed., Letters of Richard Henry Lee, 1: 331-32. Ballagh printed Lee’s retained copy of this letter, which is in Lee’s hand. The reference to Lee eating wild pigeons is in a note at the bottom written by someone else, but it seems likely that writer had this detail from Lee. [↩]

- Richard Henry Lee to William Lee, May 1773, quoted in Oliver Perry Chitwood, Richard Henry Lee, Statesman of the Revolution (Morgantown: West Virginia University Library, 1967), 21. [↩]

- Benjamin Ogle Tayloe, “American Gentlemen of the Olden Time, Especially in Maryland and Virginia,” Tyler’s Quarterly Historical and Genealogical Magazine, vol. 2, no. 2 (October 1920), 93. This essay was first published in the New York Spirit of the Times in 1851. Tayloe was quoting what he described as “a late letter” from an “old lady” dated Locust Farm, Westmoreland County, Virginia. [↩]