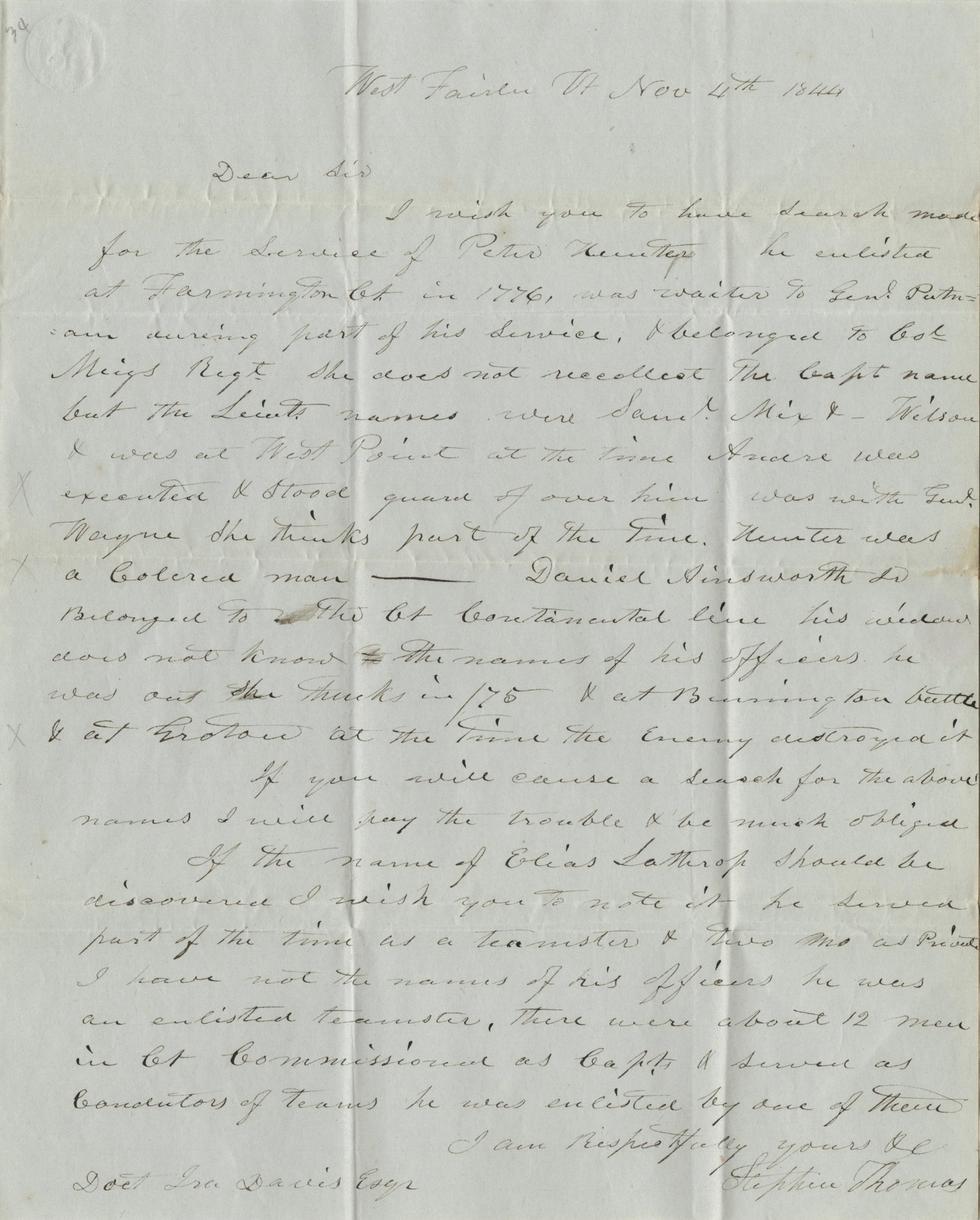

On November 4, 1844, Stephen Thomas of rural West Fairlee, Vermont, wrote to Dr. Ira Davis, an old friend then in Connecticut. Thomas explained that the widow of a Revolutionary War soldier named Peter Hunter had approached him for help in securing a widow’s pension. In 1832 Congress had passed an act providing pensions to nearly all surviving soldiers of the Revolutionary War. Tens of thousands of men had qualified and received annual pension payments. In the years that followed, Congress extended those benefits to the widows of Revolutionary War soldiers — first to women who were married to soldiers during the war and later to any widow whose husband had borne arms in the war, so long as she had not remarried.

Peter Hunter had served in a Connecticut regiment and Thomas asked Davis to make inquiries in Hartford to secure the evidence Mrs. Hunter needed to document her pension claim. Thomas explained that Peter Hunter had “enlisted at Farmington Ct in 1776, was waiter to Genl Putnam during part of his service, & belonging to Col Meigs Regt. She does not recollect the Capt name but the Lieuts names were Saml Mix & _____ Wilson & was at West Point at the time Andre was executed & stood guard over him. [He] was with Genl Wayne she thinks part of the time.”

Thomas added: “Hunter was a Colored man.”1

This made documenting his service, which had ended more than sixty years earlier, a challenge. His case and many more like it challenge us today. We need to overcome that challenge so we can take the full measure of the heroic participation of African-Americans in our Revolutionary War. That war was not fought to perpetuate slavery. It was fought to establish American independence and create a nation dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal — a proposition we are struggling to realize in the lives of men and women of our own time.

The service of black soldiers in the Revolutionary War was poorly documented. Often the best evidence is found in fugitive letters like this one, which survives entirely by chance. The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection, The Society of the Cincinnati

Despite the passage of so many years, Mrs. Hunter’s brief account of her husband’s service makes perfect sense. Free blacks were widely employed as servants in the first years of the Revolution, which is consistent with her recollection that her late husband began as a servant to Israel Putnam. So does her account of his later service in a Connecticut regiment, at a time when chronic manpower shortages had eroded opposition to the service of black troops. The regiment she described was the Sixth Regiment of the Connecticut Continental Line, commanded by R. Jonathan Meigs. The light infantry of the regiment participated Anthony Wayne’s successful attack on the British fort at Stony Point in 1779. The regiment was stationed at West Point and was there in the fall of 1780 when British Major John André was imprisoned and executed for his role in Benedict Arnold’s treason.

Ira Davis was probably struck by the widow’s recollection that her husband had stood guard over André at West Point because his own father, Moses Davis, had served at West Point and had also stood guard over André. We know this because we have a pension file for Moses Davis documenting his service in the Lexington Alarm, his participation in the Siege of Boston, and his later service in the Continental Army.2

No such pension file for Peter Hunter survives, probably because documentation of his service consistent with pension regulations could not be produced. Based on his widow’s recollections Davis would have been able to draft an acceptable declaration, but Connecticut officials would have been hard pressed to confirm his service.

Fourteen or fifteen African-American men from Farmington served in the war. Among them, as Davis may have learned, was one listed simply as “Peter” with the notation “Negro.” Connecticut officials would probably have hesitated to confirm that this man was the Peter Hunter whose widow was living in Vermont. She was unlikely to have been able to direct Davis to living witnesses who could corroborate her declaration, and finally, pension examiners might have rejected her application for inadequate proof of her marriage to Hunter, since black marriages were not as well documented as white marriages.

The evidence is too thin to know what happened to her case. Perhaps she died before submitting a pension application. Perhaps Thomas, as her agent, advised her that they lacked the documentation needed for a successful application and she gave up. Compiling the evidence required to secure a pension was daunting to most veterans and even more difficult for widows. It was far more challenging for African-American veterans and their widows, who were required to produce the same kinds of official evidence as their white peers but for whom such evidence was often unavailable or very difficult to secure.

The challenges were not insurmountable. Black veterans and their widows did manage to secure pensions. Chatham Freeman, another African-American veteran of the Sixth Connecticut, secured a pension under the Pension Act of 1818. But many others were turned away in frustration. Their loss is our loss as well, because it deprives us of the rich documentation of their service that their pension declarations and the supporting documents would otherwise provide. We learn just enough about Peter Hunter — about his relationship with Israel Putnam, the likelihood that he served in the storming of Stony Point, and his role in the trial and execution of John André — to feel that loss.3

We can make out the shadows of what might have been, realizing that we may never know his full story. On the eve of the Revolution there were about 3,000 black males over the age of sixteen living in Connecticut, and at least 820 of them served in the war. Peter Hunter was one of them. After the war he moved to Vermont, which undoubtedly appealed to him because Vermont constitution of 1777 had abolished the enslavement of men over twenty-one and women over eighteen, though it left younger slaves in bondage. Slavery persisted in Vermont, much diminished, for another generation, but it was more receptive to free blacks than most of New England.

Hunter was not the only black veteran to move to Vermont. “Hearing flattering accounts of the new state of Vermont,” black veteran Jeffrey Brace left Connecticut shortly after the war and settled in Vermont, where the emancipated slave supported himself as a farm laborer, working for wages for the first time. “Here I enjoyed the pleasures of a freeman; my food was sweet, my labor pleasure: and one bright gleam of life seemed to shine upon me.”4

We can only hope that the same “bright gleam of life” shined on Peter Hunter in Vermont. He is one of thousands of black veterans whose full story eludes us. Something like 9,000 black Americans served in or with the armed forces that won American independence — in the Continental Army and Navy, in the militia, on privateers, and as teamsters, servants to officers, and in other roles. They thus made up over four percent of the men in the armed forces during the war, but their average term of service, typically four years or more, was much longer than that of white soldiers and sailors, who generally served less than a year. Thus at any one time, black soldiers, sailors, and support personnel probably accounted for between fifteen and twenty percent of the effective strength of the armed forces. They were particularly conspicuous during the latter stages of the war, when white recruitment slowed considerably.

By the 1840s the memory of African-American veterans of the Revolutionary War had faded. “Of the services and sufferings of the Colored Soldiers of the Revolution,” poet John Greenleaf Whittier wrote in 1847, “no attempt has, to our knowledge, been made to preserve a record. They have had no historian. With here and there an exception, they have all passed away, and only some faint traditions linger among their descendants. Yet enough is known to show that the free colored men of the United States bore their full proportion of the sacrifices and trials of the Revolutionary War.”5

Neither Peter Hunter nor his widow — whose name we do not even know — ever collected a pension for his service in the Revolutionary War. We can now only pay our debt to him, and thousands like him, by struggling to recover the memory of their service and by assembling and interpreting the evidence, faint and forgotten as it may be, of their courage and commitment to the cause of freedom.

Notes

- Stephen Thomas to Ira Davis, November 4, 1844, Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection, The Society of the Cincinnati. [↩]

- Pension File of Moses Davis, W19147, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, Record Group 15: Records of the Veterans Administration, National Archives. [↩]

- Pension File of Chatham Freeman, S36524, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, Record Group 15: Records of the Veterans Administration, National Archives. [↩]

- Brace told his story to a young lawyer in Vermont who wrote and secured its publication as Benjamin F. Prentiss, The Blind African Slave, or Memoirs of Boyrereau Brinch, Nick-Named Jeffrey Brace (St. Albans, Vermont: Printed by Harry Whitney, 1810). [↩]

- John Greenleaf Whittier, “The Black Men of the Revolution and the War of 1812,” The National Era, Washington, D.C., July 22, 1847. [↩]