We celebrate the Fourth of July — the day the Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence — as our Independence Day. The declaration is our manifesto of national purpose and celebrating it is altogether fitting and proper. But doing so obscures how we achieved our independence, which required much more than a declaration. It required winning a war of eight years against one of the world’s great powers.

Remember that on October 19 — the anniversary of the American triumph at Yorktown. Fighting dragged on for more than a year thereafter, but the victory at Yorktown was the decisive event in the long and savage war that secured our independence. If Congress, in its vast wisdom, decides to abandon Columbus Day — which seems only a matter of time — Yorktown Day ought to take its place as a national holiday.

Before we could win our independence we had to decide that we were independent, or at least that we wanted to be. We decided that on July 2, 1776.

That decision seems inevitable to us, in hindsight, but it did not seem so to many Americans in the spring of 1776. They could not see, as we can, the consequences of American independence: their ultimate victory, the establishment of a continental republic and its steady rise in economic and political influence, the development of an American national identity, and the expansion of natural and civil rights to ordinary Americans, ultimately including the enslaved, women, and the broad range of people who had been disadvantaged, discriminated against, and exploited for centuries. They did not know, as we do, that the independent United States would become a refuge for oppressed and impoverished people from every part of the world and a model for the world of what free people can accomplish. They could not imagine that in the twentieth century, the United States would become the most powerful nation in the world, and would use that power to defend the Earth against tyrants intent on world domination.

The Continental Congress reflected the uncertainty of the people. The delegates of the four New England colonies and Virginia were all in favor of declaring American independence, but many of the other delegates and the people they represented were divided, uncertain, or openly opposed to separating from the empire. John Adams, who was determined to declare independence, understood the conflicting emotions the idea of separation produced. “Hope fear, joy, sorrow, love, hatred, malice, envy, revenge, jealousy, ambition, avarice, resentment, gratitude, and every other passion, feeling, sentiment, principle, and imagination were never in more lively exercise than they are from Florida to Canada, inclusively.”1

The colonists could see great risks and the potential for calamity. The New York and Pennsylvania delegates were under strict orders from their assemblies, which distrusted the radicalism of New England, to oppose independence. The Maryland delegation was under similar orders. Adams could make no sense of Maryland. “So eccentric a Colony,” he wrote, “sometimes so hot, sometimes so cold,” that he could not predict what it would do.2

It soon became clear that the people of Pennsylvania, or at least Philadelphia, were more determined than their assembly for separation from Britain. A popular meeting in the State House yard called for independence and condemned the assembly. On June 5 the assembly relented and appointed a committee to prepare new instructions for the Pennsylvania delegates to Congress, permitting them to vote with the other delegates.

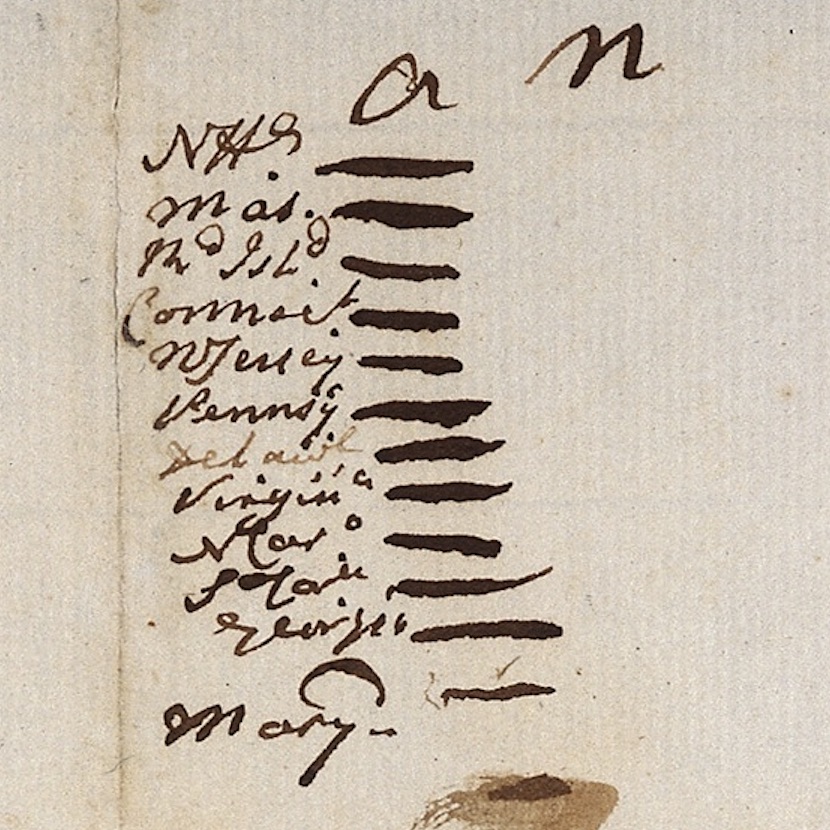

Charles Thomson, secretary to the Continental Congress, almost left “united” out of his official copy of what he called the “resolution for independency” adopted on July 2, 1776. National Archives

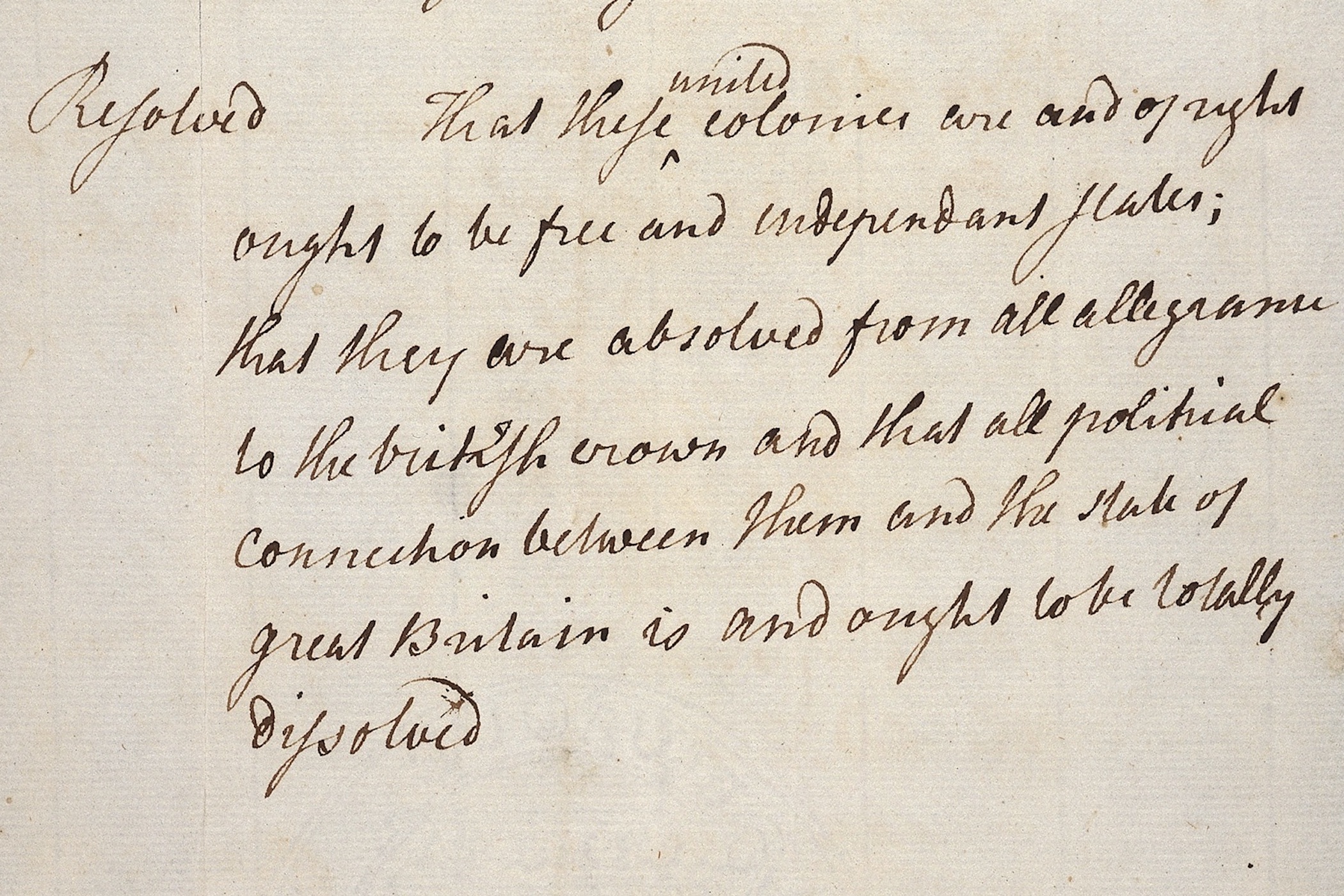

That was enough for the advocates of independence in Congress. On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee introduced a resolution:

That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, Free and Independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.3

Despite their new instructions, the Pennsylvania delegates were still divided. Maryland remained uncertain and New York was forbidden to vote for independence. Delaware’s vote depended on who was in attendance. No one knew how New Jersey’s delegates would vote. Under the circumstances further consideration of the matter was postponed until July 1. In the meantime Congress appointed a committee of five to prepare what was called “a declaration of independence.” The members of the committee were John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Robert Livingston of New York, and Roger Sherman of Connecticut.

Franklin and Adams were the most prominent members of the committee, but neither of them showed any interest in drafting the declaration. Adams convinced Jefferson to do the work, explaining that “a Virginian ought to appear at the head of this business.” Adams said that he could not do it because “I am obnoxious, suspected, and unpopular.” Finally, Adams insisted, “You can write ten times better than I can.” Adams was not as unpopular as he claimed and he was a skilled writer. In truth, Adams had to spend June politicking for votes for independence and left the work of writing the declaration to the shy, bookish Virginian.4

While Jefferson wrote, Adams devoted his time to winning over reluctant delegates. When July 1 came, Adams spoke once more in favor of independence and John Dickinson spoke eloquently on the other side. New Jersey and Maryland joined the majority for independence. Delaware remained divided, but one of the delegates in favor of independence sent a messenger to persuade the absent Caesar Rodney to ride to Philadelphia to break the tie. Rodney’s wife was ill and he was suffering from cancer, but he rode through the rain to reach Philadelphia the next day. New York’s delegates were still forbidden to vote for independence, but they agreed to abstain. The South Carolina delegation wavered, but Richard Henry Lee persuaded its leaders vote in favor of independence if Delaware and Pennsylvania did so. In the seven-member Pennsylvania delegation, four delegates were still opposed to the Lee resolution, but John Dickinson and Robert Morris agreed to withhold their votes and allow the delegation to support independence by a vote of three to two.

With this simple tally Charles Thomson recorded the most important decision in American history. Twelve states delegations voted for independence. The New York delegation, lacking instructions to support the measure, abstained. And with that, on July 2, 1776, the United States chose to be an independent nation. National Archives

Lee’s resolution in favor of independence passed on July 2, with twelve states in favor and New York abstaining. In a long life devoted to public service, this was John Adams’ finest moment. A New Jersey delegate to Congress, Richard Stockton, said that “the man to whom the country is most indebted for the great measure of independency is Mr. John Adams of Boston. I call him the Atlas of American independence. He it was who sustained the debate, and by the force of his reasoning demonstrated not only the justice but the expediency of the measure.”5 On July 3, Adams wrote to his wife, Abigail: “Yesterday the greatest Question was debated which ever was debated in America, and a greater perhaps, never was nor will be decided among Men.”6

John Adams expected Americans would forever celebrate the glorious second of July — the day Congress voted to separate from Britain — as a national holiday, with fireworks, feasts, speeches, and parades. It didn’t turn out that way, but we should not let the day pass without remembering that our nation is based on hard choices that defy fear and doubt. Such choices won our independence and have sustained it for nearly 250 years.

Notes

- John Adams to Abigail Adams, April 28, 1776, Lyman H. Butterfield, ed., Adams Family Correspondence, vol. 1: December 1761 – May 1776 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1963), 398-401. [↩]

- John Adams to James Warren, May 20, 1776, Robert J. Taylor, ed., Papers of John Adams, vol. 4: February–August 1776 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979), 195-97. [↩]

- Journals of the Continental Congress, vol. 5: 1776 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1906), 425-26. [↩]

- John Adams to Timothy Pickering, August 6, 1822, Charles Francis Adams, ed., The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States: with a Life of the Author, vol. 2 (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1850), 2: 512-17. [↩]

- Richard Stockton to John Adams, September 12, 1821, quoted in Charles Francis Adams, ed., The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States: with a Life of the Author, vol. 3 (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1851), 56. The manuscript of this letter is in the Massachusetts Historical Society and the full text will be published in due course by the Adams Papers. The letter writer quoted, Richard Stockton (1764-1828) was a son of Richard Stockton (1730-1781), the delegate to the Continental Congress. The younger Stockton quoted his father’s tribute to Adams from memory. For Adams role in the struggle, see David McCullough, John Adams (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001), 96-136. [↩]

- John Adams to Abigail Adams, July 3, 1776, Lyman H. Butterfield, ed., Adams Family Correspondence, vol. 2: June 1776 – March 1778, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1963), 27-29. [↩]