John Schrank shot Theodore Roosevelt in Milwaukee on the evening of October 14, 1912. The former president, running for reelection after nearly four years out of office, had just emerged from a hotel on his way to give a speech at the city auditorium. Roosevelt climbed into an open car waiting to take him to the auditorium and stood to wave to a large crowd. As the crowd pressed around the car, Schrank made his way to the front, extended his arm between two men, and shot Roosevelt with a .38 Colt revolver at a distance of about five feet.

Anyone who imagines this was an anomaly in a more civilized time or that public life is now coarser, less stable, and more violent should recall that Roosevelt had lived through decades marred by lynching, strikes ending in gunfire, bombings, riots, civil unrest, and war. As police commissioner of New York City Roosevelt was threatened with violence many times. His office once received a pipe bomb that failed to explode. By the time Roosevelt assumed the presidency, assassins had killed three U.S. presidents — Abraham Lincoln, James Garfield, and William McKinley.

Surprisingly little had been done to prevent those crimes. Lincoln’s assassination was treated as a tragedy unique to the Civil War and prompted no increase in presidential security. There were guards at the White House, but when presidents left the mansion they often had no guards at all. A man with a pistol shot Garfield in Washington’s Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station in July 1881 when the president walked into the passenger waiting room. The gunman — a deluded, disappointed office seeker named Charles Guiteau — simply approached the president and shot him in the back at point-blank range.1

The Secret Service was first involved in presidential security in 1894, when it was assigned to investigate a plot to assassinate Grover Cleveland. For a time two agents followed Cleveland when he was in public. This was outside the scope of the Secret Service, which had been created to combat counterfeiting, but it continued in an irregular, unofficial, and as events would prove, ineffective way for several years. Three Secret Service agents were a few feet from William McKinley when he was shot while shaking hands in a receiving line in Buffalo in 1901. His murderer, Leon Czolgosz, an unemployed young man who had embraced a violent strain of anarchism, considered killing the president as an act of rebellion against capitalist tyranny.2

After McKinley’s death the Secret Service increased the number of agents assigned to protect his successor, Theodore Roosevelt, but it was not until 1906 that Congress allocated funds for presidential security. Roosevelt doubted it would make much difference. He wrote to Senator Henry Cabot Lodge that “the secret service men are a very small but very necessary thorn in the flesh,” though he thought they “would not be the least use in preventing any assault upon my life.”3

Roosevelt’s Secret Service protection came to an end in March 1909 when he turned the presidency over to William Howard Taft. The Secret Service did not protect former presidents. Nor did it protect presidential candidates. When he ran for president in 1912 Roosevelt had to provide his own bodyguards. Though they were unable to prevent the attempted assassination, they probably saved his life.

The shooting of Theodore Roosevelt has been compared to the recent attempt on the life of Donald Trump, but they were very different events. The attack on former president Trump involved a complete failure by the Secret Service to secure the site, control access, screen for weapons, and respond effectively when a threat occurred — practices developed over several decades.

Hardly any such practices existed in 1912. Until the end of the nineteenth century presidential candidates rarely campaigned for the office. They might give a few speeches close to home — in 1896 William McKinley spoke to visitors from his front porch — but most presidential candidates relied on surrogates and party leaders to promote their election. No one worried about campaign security because candidates were rarely exposed to danger. In an era marred by violence, presidential candidates were relatively safe.

That changed quite suddenly at the turn of the last century. After decades of Republican control of the White House, campaigns became more competitive and, in many ways, more democratic. Ordinary Americans wanted to see, hear, and even touch the candidates. William Jennings Bryan and Theodore Roosevelt — pioneers of modern presidential politics — embraced and embodied these changes. They appealed directly to the voters for support and accepted the personal risks involved. The shooting in Milwaukee, which nearly ended in tragedy, was a consequence of the increasingly public, democratic nature of presidential politics.

“we were seriously afraid”

Roosevelt announced his challenge to Taft for the Republican nomination in February 1912, discarding the pledge he had made in 1904 not to seek a third term. No former president had ever challenged an incumbent of his own party and none has done so since. Republican leaders denounced Roosevelt as an egotist, a demagogue, a Jacobin, an apostate, and a brawler. Republican newspapers and Taft’s surrogates charged that Roosevelt’s bid for a third term was a threat to democracy and the principle that laws, not men, should govern. Attacks on Roosevelt, a friend wrote, were “vitriolic beyond measure.”4

More than two thousand delegates, including women and black Americans, filled the Chicago Coliseum for the Progressive Party Convention that nominated Theodore Roosevelt for president in August 1905. Library of Congress — Roosevelt described basic principles of the Progressive cause in this short speech, “The Right of the People to Rule,” recorded for the Edison phonograph company at Sagamore Hill on August 16:

When party leaders rallied behind Taft and secured his nomination at the Republican convention, Roosevelt and his supporters bolted, staged their own convention, and nominated the former president as the candidate of the new Progressive Party. Roosevelt announced that he felt “as strong as a Bull Moose.” The Bull Moose became the symbol of the Roosevelt campaign — a political insurgency that all but assured Taft’s defeat.

Roosevelt’s larger challenge was defeating Woodrow Wilson. The Democratic candidate was relatively unknown, but he could depend on Democratic Party machinery and the support of newspapers aligned with the party. He also enjoyed the endorsement of William Jennings Bryan, to whom many Democrats remained fiercely loyal. Roosevelt’s only path to victory was to peel progressive Democrats — people who had voted Bryan in 1896, 1900, and 1908 — away from Wilson. It was a long shot. “I do not for a moment believe that we shall win,” Roosevelt wrote privately to his son Kermit. “The chances are overwhelmingly in favor of Wilson.”5

The Roosevelt campaign attracted large crowds at whistle stops like this one in Burlington, New Jersey, with advertising and broadsides posted in towns where Roosevelt was scheduled to speak. Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard University — Roosevelt usually delivered a short speech like this one, recorded on September 22:

Roosevelt adopted Bryan’s tactics to win Bryan’s supporters. After the Progressive Party convention Roosevelt campaigned in New England and then left on a whistle-stop tour across the West and back to New York through the South, giving major speeches in cities and short speeches from the back of a private rail car at towns along the way. Bryan had pioneered this kind of campaign in 1896, becoming the first major party candidate to tour the country appealing for support. When Bryan ran for president in 1900, Roosevelt — then McKinley’s running mate — pursued him around the country by rail.6

Roosevelt couldn’t compete with Bryan as an orator, but he made up with energy and patriotic fervor what he lacked in grace. On the campaign trail he developed a remarkable rapport with regular Americans. As president after McKinley’s assassination Roosevelt traveled the country speaking from the back of his train. Much of his popularity rested on these appearances. He was the first sitting president most Americans had ever seen.

Adoring audiences turned out to greet Roosevelt and he returned their affection with a warm familiarity the cartoonists mocked and his opponents envied. “Children, don’t stand so close to the car,” he said at whistle stops, “it might back up, and we can’t afford to lose any little Bull Mooses.”7 This Samuel Ehrhart cartoon was published in Puck on October 2, 1912. Early movie makers captured some of the campaign, including this film of Roosevelt in North Dakota:

Campaigning that way posed considerable security risks. At whistle stops crowds pressed right up to the observation platform, just a few feet from Roosevelt. Local policemen were often present, but in photographs they are typically right in front, looking up at Roosevelt rather than scanning the crowd for threats. There was no security perimeter and no metal detectors to screen out handguns, which recent innovations had made cheap, powerful, accurate, and easy to conceal. When Roosevelt left the train to speak in cities, he traveled in an open car at slow speed past spectators lining the streets. He often made himself an even easier target by standing up in cars to wave to his supporters.

As a candidate Roosevelt frequently rode in an open car within arm’s reach of spectators — here in Chicago during the Progressive Party convention in August. Police were stationed along his route but they would have been hard pressed to prevent a shooting. Library of Congress

Roosevelt and Wilson — who engaged in a whistle-stop campaign of his own — accepted these risks to secure press coverage. Reporters rode with the candidates and telegraphed reports on the latest speeches, which the candidates aimed at newspaper readers as much as the people who flocked to train stations and filled the city auditoriums. This, too, was new, as was the rapid transmission of photographs from the campaign trail.8

Already one of the most accomplished newspaper reporters of his generation when he covered the Roosevelt presidency, O. K. Davis resigned his post as as Washington bureau chief of The New York Times to manage press relations for the Roosevelt campaign. Library of Congress

Oscar King Davis, who had resigned as New York Times Washington bureau chief to serve as Progressive Party secretary, managed relations with the press. He assembled a staff to help the candidate prepare a steady stream of new material, organized Roosevelt’s October tour of the Midwest, and traveled with Roosevelt on that trip as de facto communications director. Reporters from major newspapers and news services traveled with the Roosevelt campaign in their own rail car. In photographs taken at whistle stops they can be seen, note pads in hand, on the observation platform.

Two bright secretaries, Elbert Martin and John McGrath, worked with Davis to manage correspondence, took dictation, and helped Roosevelt get his remarks in order. When the text of an important speech was finished the staff sent advance copies to major newspapers and news services. The former president’s young cousin Philip Roosevelt collected and distributed news about the Wilson campaign so Roosevelt could respond to Wilson in his remarks. Henry Cochems, a Wisconsin Progressive familiar with Wilson’s record, advised Roosevelt. Dr. Scurry Terrell, the campaign physician, helped him deal with the strain of giving several speeches a day without the aid of amplification. Charles Duell, Jr., a son of Roosevelt’s New York campaign chairman, was nominally a secretary but had no clearly defined role.9

Roosevelt entrusted his security to his friend Cecil Lyon of Texas, longtime leader of the state Republican Party and a skilled hunter and marksman. He marveled a Roosevelt’s charisma. “Damned if I know how he does it. He doesn’t have to makes a speech; in fact, half the time he doesn’t make one. He says ‘Friends, I’m glad to see you,’ and they go off and vote for him.”10 Library of Congress

In the absence of Secret Service protection, Roosevelt recruited Cecil Lyon, a Texas Republican and one of his favorite hunting companions, to manage security. McGrath and Martin doubled as bodyguards. They were bruisers. McGrath, who had gone to New York to study law, was a rough-and-tumble hockey player recognized as the best right wing in the city. Martin had worked on a surveying crew in Wyoming, shoveled coal into locomotives, and played college football before going to law school. McGrath or Martin usually walked beside Roosevelt in public and were prepared to deal roughly with anyone who seemed like a threat. Lyon often led the way with a semi-automatic pistol in his pocket.11

No one had ever attempted to kill a presidential candidate, but Roosevelt and the men around him were concerned about the possibility. The campaign became so bitter, one wrote, “and the assaults on the Colonel were of so virulent and inflammatory a character, that we were seriously afraid of attempts at assassination.”12

“football tactics”

By the end of September Roosevelt was thoroughly tired of giving the same speeches over and over. On the train he entertained reporters by mimicking his own style and performing his stock lines in a high falsetto. In private he wrote “I am hoarse and dirty and filled with a bored loathing of myself whenever I get up to speak.” But he kept at it.13

Roosevelt and his staff left New York on October 7 for Michigan, Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Illinois — states essential to his success. He devoted two days to Michigan, speaking in Detroit, Flint, Saginaw, and Bay City on October 8 and in Houghton, Cheboygan, and Marquette on October 9, with whistle stops along the way. He crossed into Minnesota on October 10 and spoke that night in the opera house in Duluth.

When Roosevelt walked in public on his midwestern tour, his secretaries John McGrath (at left, looking at the camera) and Elbert Martin (at right, looking to his left) served as bodyguards. Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard University

Everywhere Roosevelt went crowds jostled his staff trying to get close. In Saginaw Martin shoved a man into the gutter. Roosevelt told Martin not to be so rough. Crowds gathered in and around train stations and hotel entrances and outside auditoriums where Roosevelt went to speak. “On such occasions we formed a ring of our own men around the Colonel,” Davis wrote, “and pushed, shoved, and hauled until we got him from his car to the motor that was to take him to the hotel, and again from the motor into the hotel,” adding that “it was extremely difficult for any one to get at him without first encountering one of us.” In Duluth it was hard to get Roosevelt out of the station and into a car, even using these “football tactics.” In the hotel lobby crowds pressed against the staff, “demanding a sight of the Colonel and endeavoring to touch him, to pat his shoulder.” Only with the greatest difficulty were they able to get Roosevelt up the stairs and into a room.14

Roosevelt gave two more speeches in Duluth the next morning before heading to Wisconsin, where the campaign faced difficulties of another sort. Wisconsin Senator Robert LaFollette, a leading Progressive, refused to support Roosevelt. He had announced his own challenge for the Republican nomination several months before Roosevelt and was frustrated when the former president entered the race. LaFollette thought Roosevelt was a poser who would sacrifice Progressive goals to mollify business interests. Roosevelt was determined to win over Wisconsin Progressives loyal to LaFollette.15

Hiram Johnson, Roosevelt’s running mate, had aggravated this problem. In September he was to have been the guest of honor at a luncheon in Milwaukee organized by the local Progressive committee. Governor Francis McGovern had agreed to come and speak on behalf of the Progressive ticket, after which Johnson was to address several thousand people at the Wisconsin State Fair. Johnson was tired and thought speaking at an agricultural fair was beneath him. He failed to appear. The governor withheld his endorsement and the organizer, Henry Cochems — a close associate of LaFollette and McGovern who had broken with the senator by backing Roosevelt — was mortified.16

A large crowd waited for Roosevelt in Oshkosh on October 11. People climbed on the station roof, on top of boxcars, and up utility poles to catch a glimpse of the former president, whose train arrived shortly after this photograph was taken. Oshkosh Public Museum

The former president reached out to LaFollette’s supporters in a speech in Oshkosh on Friday, October 11, praising the senator for having “done so much for the progressive cause” and expressing regret that “because of his antagonism to me he must range himself against the progressive movement in this campaign.” Roosevelt planned to win over Wisconsin Progressives with a major speech in Milwaukee on Monday, October 14. He spent the weekend campaigning in Chicago, including a speech in an open tent beside Lake Michigan that left him tired and hoarse. The party left for Milwaukee around three o’clock on Monday afternoon.17

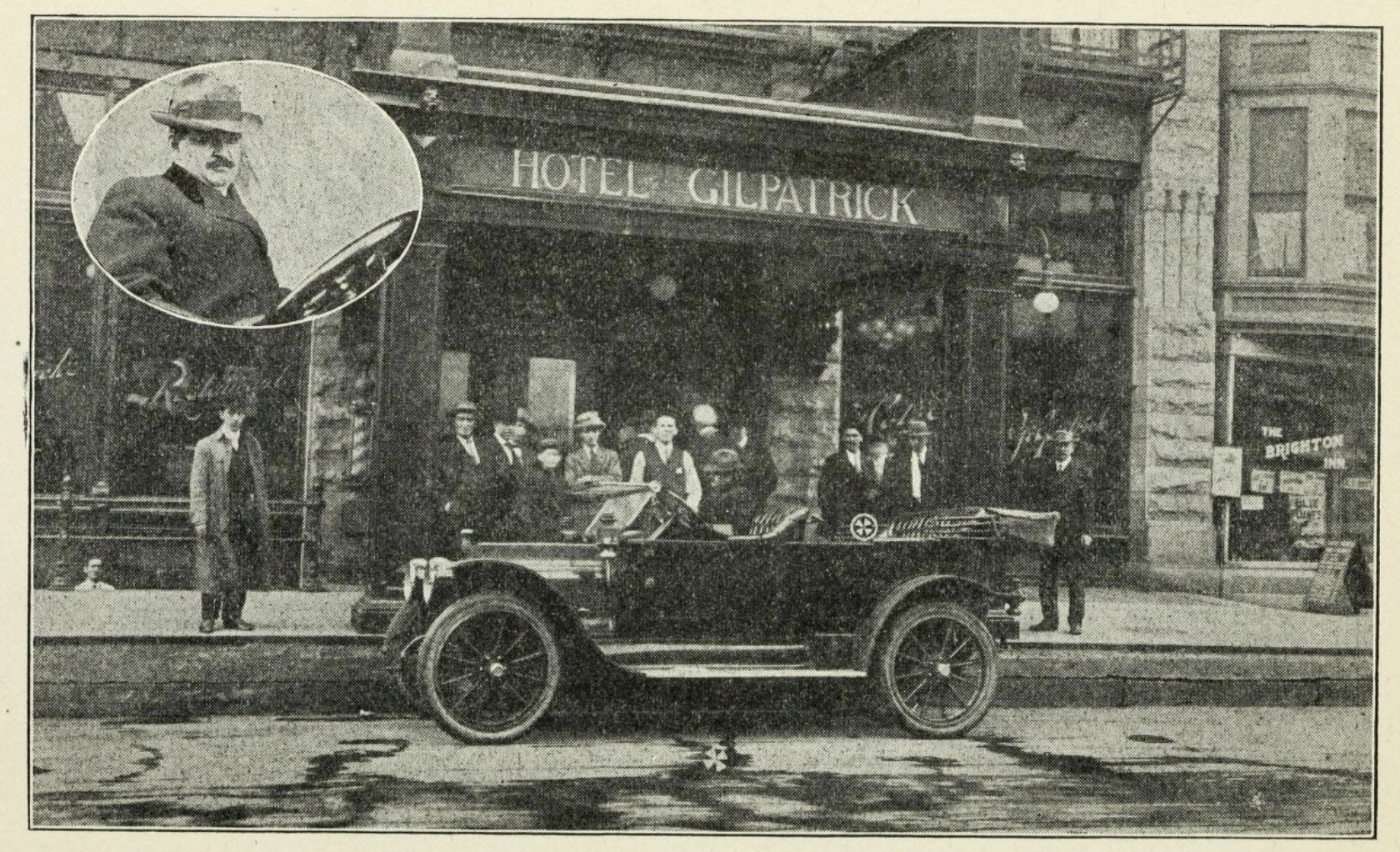

They reached Milwaukee about six o’clock. Roosevelt’s staff wanted him to stay in his railway car and go directly to the auditorium at eight, but local Progressives had booked a suite and arranged for a private dinner at the Hotel Gilpatrick, a few blocks from the auditorium. They had even secured an additional bodyguard — a former Rough Rider named Alfred O. Girard, who boarded the train in Racine. Francis Davidson, chairman of the Milwaukee County Progressive Committee, boarded the train when it reached Milwaukee and appealed to Roosevelt to go to the hotel. Determined not to disappoint anyone, Roosevelt agreed to go. “I want to be a good Indian,” he told Davis.18

The Gilpatrick was not the city’s most elegant hotel — it had been built as a trunk factory — but the owner supported the Progressive cause. The hotel was threadbare and soon to be demolished when this photograph was taken in the 1930s. The Hyatt Regency Milwaukee now occupies the site. Milwaukee Public Library

A few minutes later Roosevelt left the train with Lyon on one side and Girard on the other. The sun set at Milwaukee at 5:10 p.m. that day so by the time Roosevelt got in the car to go to the hotel evening had fallen. It was too dark for anyone to have photographed Roosevelt’s arrival, the motorcade to the hotel, or the shooting, which occurred on a dark street hours later. Publications about the shooting are often illustrated with photographs taken elsewhere or at other times. Some were taken when Roosevelt stopped in Milwaukee at the beginning of his western tour. Others are generic photographs of Roosevelt giving a speech or waving to supporters. None of them was taken on October 14, 1912.19

Despite the hour, the streets between the station and the hotel were lined with spectators who cheered as the motorcade passed. A large crowd had gathered outside the hotel, but thanks to the Milwaukee police Roosevelt’s party went in without having to force its way through a mob of admirers. Roosevelt went straight to his room and promptly fell asleep in a rocking chair. “It was the only time,” Davis wrote, “in all the campaign trips I made with him, that I ever saw him sleep before bedtime.”20

Roosevelt and his staff came down to dinner shortly before seven. Girard stood guard outside the door. In the dining room Roosevelt was in good spirits. Elbert Martin remembered that he told stories and kept everyone entertained. Dinner ended shortly before eight and the party went back upstairs. A few minutes later Francis Davidson came to the suite to see if the former president was ready to go. He assured Cecil Lyon that the police had the crowd outside under control. With that, Roosevelt went downstairs to the waiting car.21

“I leaped with all my power . . . to intercept the bullet”

The would-be assassin was waiting for Roosevelt in the crowd outside the hotel. An out-of-work New York City bartender, John Schrank suffered from paranoid delusions and was fixated on the idea that Roosevelt’s bid for a third term was a mortal danger to the republic. He had borrowed $350 from his landlord’s son, spent $14 on a .38 Colt revolver and six bullets, and followed Roosevelt around the country for twenty-four days, looking for his opportunity. In Chattanooga he came within ten feet of Roosevelt but lost his nerve. He had an opportunity in Chicago but decided that killing Roosevelt in Chicago would be a disservice to the city. He had no such scruple about Milwaukee. He arrived ahead of Roosevelt, checked into a cheap hotel, and waited. He drank beer in a bar across from the Hotel Gilpatrick while Roosevelt was having dinner, then pushed his way through the crowd until he was close to the car.22

Schrank had only been in police custody a short time when this photograph was taken. Distributed immediately, it appeared in newpapers across the country the morning after the shooting. Library of Congress

We can reconstruct the attempted assassination using the statements of participants and eyewitnesses. Each had his own perspective and their accounts do not agree in some details. The street was dark, illuminated slightly by light from the hotel. It was crowded and noisy. The events from the moment Schrank fired until he was apprehended and Roosevelt’s car left the scene lasted only a minute or two. Roosevelt himself never wrote a detailed account of the shooting, though he alluded to it in correspondence several times. Schrank answered a few questions from the police and at his trial a month later, but if all we had was the testimony of the gunman and his victim we would be unable to piece together what happened.23

Accounts of the shooting were published in newspapers beginning on October 15, but these must be treated with great caution. Then, as now, journalists writing in haste to meet deadlines borrowed from one another, repeated assumptions as facts, and circulated confused and inaccurate reports. No reporter was on the scene — the journalists traveling with the campaign were either finishing dinner elsewhere or already at the auditorium — and even if one had been in the crowd outside the hotel he would have been hard pressed to produce an accurate account of what happened based on personal observations alone. Collecting and sifting through eyewitness statements to construct such an account would taken have more time than they could spare. This was the biggest story in a decade and they had missed it. They gathered as much information as they could get, wrote as quickly as they could, and filed their stories by telegraph in time to make the morning papers.24

Fortunately we have better evidence and the time to analyze it carefully. Two days after the attack, District Attorney Winifred Zabel interviewed several people who were present when Schrank fired. Local Progressives published their statements a few weeks later. Zabel called some of those witnesses to testify at Schrank’s trial in Milwaukee Municipal Court on November 12. Others offered testimony at the trial or made statements to Milwaukee reporters. These were all contemporary statements, made within days of the shooting by people who remained in the city.25

Roosevelt and most of his party left for Chicago a few hours after the shooting and none returned for Schrank’s trial. A reporter for the Chicago Tribune interviewed Philip Roosevelt and Elbert Martin on October 15. Martin, who played an important role in apprehending Schrank, later wrote a detailed account of the evening’s events. Martin’s account survives in typewritten form, but it is not dated. He lived until 1956 and undoubtedly told his story many times. That his account is not dated is unfortunate, but it does not conflict with the statement he made on October 15 nor in material ways from account offered by others.26

O. K. Davis wrote three accounts of the shooting. The first was a report to George Perkins, chairman of the executive committee of the Progressive Party, written on October 15. The second was a brief article published in Munsey’s Magazine in January 1913. Davis expanded on these accounts in his book Released for Publication: Some Inside Political History of Theodore Roosevelt and His Times, 1898-1918, published in 1925. The book is an invaluable account of the campaign, but Davis was still inside the hotel when Schrank fired. He ran downstairs when he heard the shot but arrived after Schrank’s capture. Davis pieced together his account of the shooting by talking to members of Roosevelt’s party who were present.27

Roosevelt, his cousin Philip, Cecil Lyon, Elbert Martin, A. O. Girard, and Henry Cochems were in the hotel lobby a few minutes after eight, along with a seventh man, Fred Luettich, the doorman from Progressive Party headquarters in Chicago, who had come with the group to help protect Roosevelt. Dr. Terrell had a nosebleed and remained upstairs along with Davis and McGrath, who were planning to return to the railroad car to work on correspondence while Roosevelt spoke at the auditorium.28

Several hundred people — perhaps more than a thousand — were gathered in the dark outside the hotel to get a glimpse of Roosevelt. They filled the street and sidewalk in front of the hotel, but the police kept the area under the hotel canopy clear. No football tactics were needed to reach the car waiting at the curb.

George Moss (in the oval inset) parked his touring car in front on the Hotel Gilpatrick shortly after the shooting to recreate the scene for this photograph. The X in a circle indicates where Roosevelt was standing when Schrank fired. The X on the street indicates where Schrank stood. The photograph was published in Oliver E. Remey, Henry F. Cochems, and Wheeler P. Bloodgood, The Attempted Assassination of Ex-President Theodore Roosevelt (Milwaukee: Progressive Publishing Company, 1912).

The party left the building — Martin and Lyon in front, Roosevelt following with Cochems on one side and Girard on the other, and Philip Roosevelt and Luettich behind — and walked to the car. It was a 1912 Rambler Country Club owned and driven by George F. Moss, vice president and treasurer of the Western States Envelope Company. Thomas Taylor, the company president, cranked the engine from the front of the car when he saw Roosevelt coming out of the lobby. Then he got in next to Moss, who was in the driver’s seat. The car was facing south — to Roosevelt’s right as he came out of the hotel. A second car, left by Wheeler Bloodgood, was behind the Rambler. The Rambler was a right drive automobile — Moss was thus seated on the side closest to the curb. The crowd on the street was within a few feet of the passenger side of the car, making it impossible for anyone to get in the car on that side.29

Martin opened the rear driver’s side door and motioned to Cochems to get in first. In such situations Martin or McGrath usually got in first and sat between Roosevelt and the crowd on the street, but Cochems was either unaware of this precaution or overlooked it. He politely deferred to Roosevelt, who got in first and thus wound up exposed on the passenger side nearest to the crowd. Cochems got in after him and remained standing beside Roosevelt. Cecil Lyon, having seen Roosevelt to his car, stood nearby on the sidewalk. Girard started to get in to the front seat and was working his way past Moss and Taylor, no doubt awkwardly, to reach the seat on the passenger side in front of Roosevelt. With Roosevelt and Cochems in the car, Martin stepped up on the running board and was preparing to sit down beside Cochems. Philip Roosevelt was behind Martin and was to sit beside the door.30

The people cheered when they recognized Roosevelt. He stood and raised his hat to acknowledge the cheers with no aide between him and danger. Martin was looking toward the street as he stepped into the car. At that moment, he recalled:

I suddenly noticed a man stand forth from the crowd, rush to the automobile and as I caught the glint of the blue from his gun as he raised it to fire I leaped with all my power on the impulse to intercept the bullet or knock the gun out of his hand. I was a fraction of a second too late for he fired as I leaped. . .

Clearing the automobile I landed directly on the man. As I tackled him and bore him to the pavement my arm locked around his neck. He had the gun in his right hand and tried to force it between his body and left arm in an endeavor to shoot again. I met the muzzle with my left hand which then went to his wrist and with a wrench from me he dropped his gun.31

A. O. Girard, the former Rough Rider, remembered this moment a little differently. He was just stepping into the car at the driver’s door and working his way past Taylor when he saw Schrank raise the revolver. “The end of the gun was probably six feet raised to the level of his eye; he took a good aim.” At that moment “somebody else” — Martin — “jumped from the other end of the machine.” Girard dove for Schrank, too, and in an instant, Girard remembered, “We were all on the ground together.”32

Thomas Taylor remembered something similar. When Girard jumped toward Schrank, an instant after Martin, he knocked Taylor down in the car. Taylor rose to his knees and saw Martin and Girard on top of Schrank, while a third man — “he looked like a laborer,” Taylor said —grabbed one of Schrank’s arms. This was Frank Buskowsky, a bystander who was beside Schrank when he fired.33

Within seconds Sergeant Albert Murray of the Milwaukee Police Department, who had been standing on the sidewalk near the car, reached Schrank. He said that by the time he got there “Captain Girard and another man by the name of Martin, had him on the ground and I reached down to get hold of the gun, and he had the gun in the right hand, and I happened to get hold of the left hand.” However it happened, the swift actions of Martin, Girard, Murray, and Buskowsky prevented Schrank from getting off a second and potentially fatal shot.34

Cecil Lyon was on the sidewalk when Schrank fired. He drew his automatic pistol and ran around the car, looking for a shot at the attacker in the tangle of men on the street. He immediately caught sight of two or three other men rushing forward and met them at gunpoint, ordering them back. For all Lyon knew they were assassins intent on finishing the job. They may have been police detectives trying to help subdue the shooter. In any case, they wisely stepped back.35

Milwaukee detectives Louis Hartman and Harry Ridenour and patrolman Valentine Skierawski were also on the sidewalk under the hotel canopy when Schrank fired. Hartman testified at Schrank’s trial that he ran around the rear of the car and saw Murray “and some other officers and some citizens there, that was all down there on the street, on the pavement, and I got down there and got hold of one of his hands, and after some difficulty got him up on his feet.”36

Ridenour was not deposed on October 16 nor did he testify at Schrank’s trial, but he was in Leavenworth, Kansas, on police business four days after the shooting and spoke to a reporter. “I was standing about fifteen feet from the colonel when the shot was fired,” Ridenour said. He credited Martin with saving Roosevelt’s life, adding “the fact that the crowd was so large and that there were so many detectives and police officers on guard made it impossible for the assailant to take deliberate aim.”37

Skierawski’s recollection differed a little from the others. He testified that he was on the sidewalk five or six feet from the car when he heard the shot and that he went around the car and saw only two men on the pavement and he “dropped on top of them.” By other accounts the pile of men on the ground included Schrank, Martin, and Girard, with Buskowsky and Sergeant Murray grabbing for the gun but still on their feet.38

Roosevelt was stunned by the shot. Thomas Taylor remembered turning to see Roosevelt sitting in his seat for a moment and then standing back up. Cochems remembered that Roosevelt’s knees buckled briefly but that he steadied himself on the side of the car and then reached for the back of the seat. Cochems, who said he had not sat down, put his arm around Roosevelt to steady him and asked Roosevelt if he had been hit.

“He pinked me, Harry,” Roosevelt replied, using a word meaning pierced, jabbed, or pricked. Roosevelt knew he had been hit in the chest but he later explained that “I had no real pain. The wound felt hot.” He could breathe without difficulty and did not taste blood in his mouth. An avid hunter, he knew that an animal expels blood through its mouth when a bullet pierces its lungs. Cochems remembered that Roosevelt stood up straight and waved his hat to the crowd as a signal he was all right.39

On the pavement there was a scramble for the gun. Accounts of how Schrank was disarmed are confused and contradictory. Each participant remembered these few seconds differently. Martin wrote that he grabbed the muzzle with his left hand and wrenched it out of Schrank’s hand. Girard testified that he “had Schrank on the ground and trying to get the gun from him.”40

Martin wrote that he had Schrank on the ground: “I placed my knee in the small of his back and then commenced to force his head back in an endeavor to break his neck, for I wanted to kill him.” Taylor remembered that Roosevelt called out “Do not kill him; bring him here,” and repeated the order five or six times. Martin thought Roosevelt said “Don’t hurt him, bring him to me.” Roosevelt himself, writing three months later, remembered saying “Don’t hurt him. Bring him here. I want to look at him.”41

In his statement on October 16 Girard said that he had Schrank by the throat and that Murray and Martin were each holding one of Schrank’s arms. He testified at trial that “we picked him up off the ground and Sergeant Murray and myself and Mr. Martin took him up to the Colonel’s automobile and handed the gun to the Colonel and he said not to hurt him.”42

Martin claimed that he jerked Schrank to his feet “and dragged him to the car and first handed Colonel Roosevelt the gun” and that Roosevelt handed the revolver to Cochems. Martin made no mention of Girard (whom he mistook for Luettich) or Murray.43

Cochems remembered that Martin, Girard and “the policeman” (Murray) dragged Schrank to the car with “three or four hands” struggling for possession of the revolver. “I succeeded in grasping the barrel of the revolver,” Cochems wrote, “and finally in getting it from the possession of a detective.” Cochems put the gun in his pocket.44

However it happened, within a few seconds of firing Schrank was disarmed and shoved against the side of the car, right in front of Roosevelt. Martin wrote that he twisted Schrank’s head up so Roosevelt could look at him. Girard wrote that “we bent his head back so the Colonel could see him.” Roosevelt did not recognize Schrank and ordered his captors to turn him over to the police. Girard and Sergeant Murray hustled Schrank into the hotel and then into the kitchen where he was held for a few minutes until a police car arrived to take him away.45

Davis, McGrath, and Terrell hurried downstairs when they heard the shot. By then the crowd had surged on to the sidewalk and was blocking access to the car. The three men fought their way through the crowd and got in the car, taking the places of Girard, who was guarding Schrank in the hotel kitchen, and Martin, who was still outside the car on the street.

By then Roosevelt had sat down. He directed George Moss, who had remained behind the wheel throughout, to drive to the auditorium. Terrell insisted on seeing the wound and he and Cochems both told Moss to drive to the hospital, but Roosevelt refused and ordered Moss to take him to the auditorium. Davis and Philip Roosevelt appealed to the former president to go the hospital to have his wound examined, but he refused. “You get me to that speech,” Roosevelt said. “It may be the last one I shall ever deliver, but I am going to deliver this one.”

That is how Davis remembered it. The auditorium was only three blocks away, but the streets were crowded with spectators. Moss drove away from the hotel at a walking pace, the crowd parting in front of the car. Martin walked beside the car and alongside Roosevelt to prevent anyone from getting too close to him. Many in the crowd — more as the car moved along — had no idea Roosevelt had been shot. They cheered as the car passed. “This is my big chance,” Martin remembered Roosevelt saying, “and I am going to make that speech if I die doing it.”46

“it takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose!”

Even driving at a walk it took no more than a few minutes to reach the auditorium, which was just three years old and the pride of Milwaukee. It could seat over nine thousand people and that night it was filled to capacity and then some. More than a thousand people were outside, unable to get in.

A crowd of over a thousand people was outside the front of the Milwaukee Auditorium when Roosevelt and his party arrived. They entered through the side door at far right. Milwaukee Public Library

Roosevelt and his party walked in the side entrance, where they went into a waiting room behind the stage. There Roosevelt allowed Dr. Terrell and three other physicians hastily recruited from the auditorium to examine the wound. The bullet had passed through Roosevelt’s thick army overcoat, his suit coat, vest and suspenders. His shirt and undershirt were soaked with blood around the entry point, but the bleeding had slowed. The bullet seemed to have lodged in his chest muscles, but no one could be sure.47

The wound indeed might have been fatal, but the bullet had passed through Roosevelt’s eyeglasses case and the text of his speech, which was in his suit coat pocket. The case was metal and the speech was some fifty pages folded double. They slowed and deflected the bullet, which lodged in Roosevelt’s chest, breaking one of his ribs but not puncturing his pleural cavity. When his family doctor, Alexander Lambert, examined Roosevelt a few days later he concluded that if the bullet had not struck the eyeglasses case and the thick folded speech it would have reached his heart and Roosevelt “would not have lived sixty seconds.48

The doctors in the auditorium waiting room insisted that Roosevelt leave at once for the hospital but he scoffed and asked if anyone had a clean handkerchief. Someone handed him one, which he used to cover the wound. He then buttoned up his clothes and said “Now, gentlemen, let’s go in.” With that the members of the party walked out on the stage and took their seats. Henry Cochems introduced Roosevelt, explaining that as the former president was leaving the hotel a few minutes earlier a man had shot at him. Most in the audience seem to have assumed that the would-be assassin had missed, and when Roosevelt walked up to the front of the stage the audience cheered.49

In all the lore about Theodore Roosevelt’s strenuous life there is no other moment like this one. Indeed American political history offers nothing like it. Roosevelt asked the vast audience “to be as quiet as possible. I do not know whether you fully understand that I have been shot but it takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose.” The audience gasped in dismay, and then, Davis wrote, “there was a tremendous burst of cheers as they realized that Colonel Roosevelt was all right.”50

On the speaker’s platform Elbert Martin collected the pages of Roosevelt’s speech as the candidate finished with them. He showed the bullet holes in the speech to a press photographer outside Mercy Hospital in Chicago on October 15.51 Library of Congress

The men in Roosevelt’s party sitting on the platform were not so sure. McGrath and Martin sat close behind Roosevelt in case he fell backwards. Dr. Terrell sat nearby, watching for signs of imminent collapse. They all watched nervously as Roosevelt pulled the text of his speech from his coat pocket. He was momentarily startled by the bullet hole through the thick stack of paper. “It was the only time I ever saw anything seem to stagger Colonel Roosevelt,” Davis wrote, “but he rallied instantly.” Roosevelt held the pages up for the audience to see. “The bullet is in me now,” he said, “so that I cannot make a very long speech. But I will try my best.”52

“When I began to speak,” Roosevelt recalled later, “my heart beat rapidly for some ten minutes, but aside from that about all the real trouble I had was that on account of my broken rib I had to breathe quick and short, so that I could not speak as loudly as usual, nor use as long sentences without breathing.”53 For several minute he extemporized. He didn’t know anything about the man who shot him, he said. “He was seized at once by one of the stenographers in my party, Mr. Martin, and I suppose is now in the hands of the police. He shot to kill. He shot — the bullet went in here — I will show you.” He opened his suit coat and revealed the blood staining his shirt. The crowd gasped.

An elderly woman near the front stood up and asked Roosevelt to go to the hospital — that the audience was afraid for him and everyone would feel better if he was cared for properly. Roosevelt thanked her, adding “If you could see me on horseback right now, I am sure you would agree that I am quite all right.” He forged on.54

Although he knew nothing about the would-be assassin, Roosevelt continued, “it is a very natural thing that weak and vicious minds should be inflamed to acts of violence by the kind of awful mendacity and abuse that have been heaped upon me for the last three months. . . . I wish to say seriously to all the daily newspapers, to the Republicans, the Democrat, and Socialist parties, that they cannot, month in month out and year in and year out, make the kind of untruthful, of bitter assault that they have made and not expect that brutal, violent natures, or brutal and violent characters . . . will be unaffected by it.”

His life wasn’t important, he insisted. The cause was all that mattered. “I am in this cause with my whole heart and soul. I believe that the Progressive movement is making life a little easier for all our people; a movement to try to take the burdens off the men and especially the women and children of this country. I am absorbed in the success of that movement.” It was the duty of every good citizen, he said, to prevent the United States from being divided permanently between the haves and the have-nots, warning that if “that day comes, the most awful passions will be let loose and it will be an ill day for our country.”

The audience hung on his words, astonished and dismayed that Roosevelt continued to speak. Men on the platform and members of the audience appealed to him to stop. He dismissed them all, insisting he was fine, though it became apparent that he was struggling to go on. Finally O. K. Davis, convinced that Roosevelt might collapse, stepped up and put his hand Roosevelt’s arm.

“What do you want?” Roosevelt asked.

“Colonel,” Davis replied quietly, “I want to stop you. You have spoken thirty-five minutes. Don’t you think that is long enough?”

“No, sir,” Roosevelt said. “I will not stop until I have finished this speech.”

Davis retreated, but Henry Cochems, a former college football player who had set records for feats of strength at Harvard, climbed off the platform and stood below to catch Roosevelt if he fell forward.55

“My friends are a little more nervous than I am,” Roosevelt said to the audience. “Don’t you waste any sympathy on me. I have had an A-1 time in life and I am having it now. I never in my life was in any movement in which I was able to serve with such whole-hearted devotion as in this.”

Roosevelt insisted that a just society embraces all its citizens without discrimination. “I ask in our civic life that we . . . pay heed only to the man’s quality of citizenship” and “repudiate as the worst enemy that we can have whoever tries to get us to discriminate for or against any man.” He was committed to the right of labor to organize, just as capital was organized, while insisting that labor repudiate violence to achieve its ends. He was opposed to child labor, to industries working women fourteen and sixteen hours a day and forcing men to work seven days a week. Wilson, he said, was for leaving these matters to state governments, committing himself to what Roosevelt called “the old flintlock, muzzle-loaded doctrine of states rights.”

Toward the end he addressed his remarks to the people of Wisconsin. Roosevelt knew that he had to win the state, along with most of the Midwest, to reclaim the presidency. LaFollette’s opposition weighed on him. The progressive cause was greater than any individual, he said. Wisconsin had “taken the lead in progressive movements,” he said, and was a source of “inspiration and leadership.” It would be a tragedy for the progressive cause “if you fail to stand with us now that we are making this national movement.”

Roosevelt was on the stage for an hour and a half. He was, a reporter wrote, “every inch courageous.” When he finished thousands cheered until they were hoarse. “When I got down from the stage,” Roosevelt remembered, “they surged around me calling out ‘Handshake, handshake,’ and much as I’d have liked to oblige them, you know that it is impossible for a man with a bullet in his chest, which for anything he knows may be mortal, to shake hands with any approach to real cordiality.”56

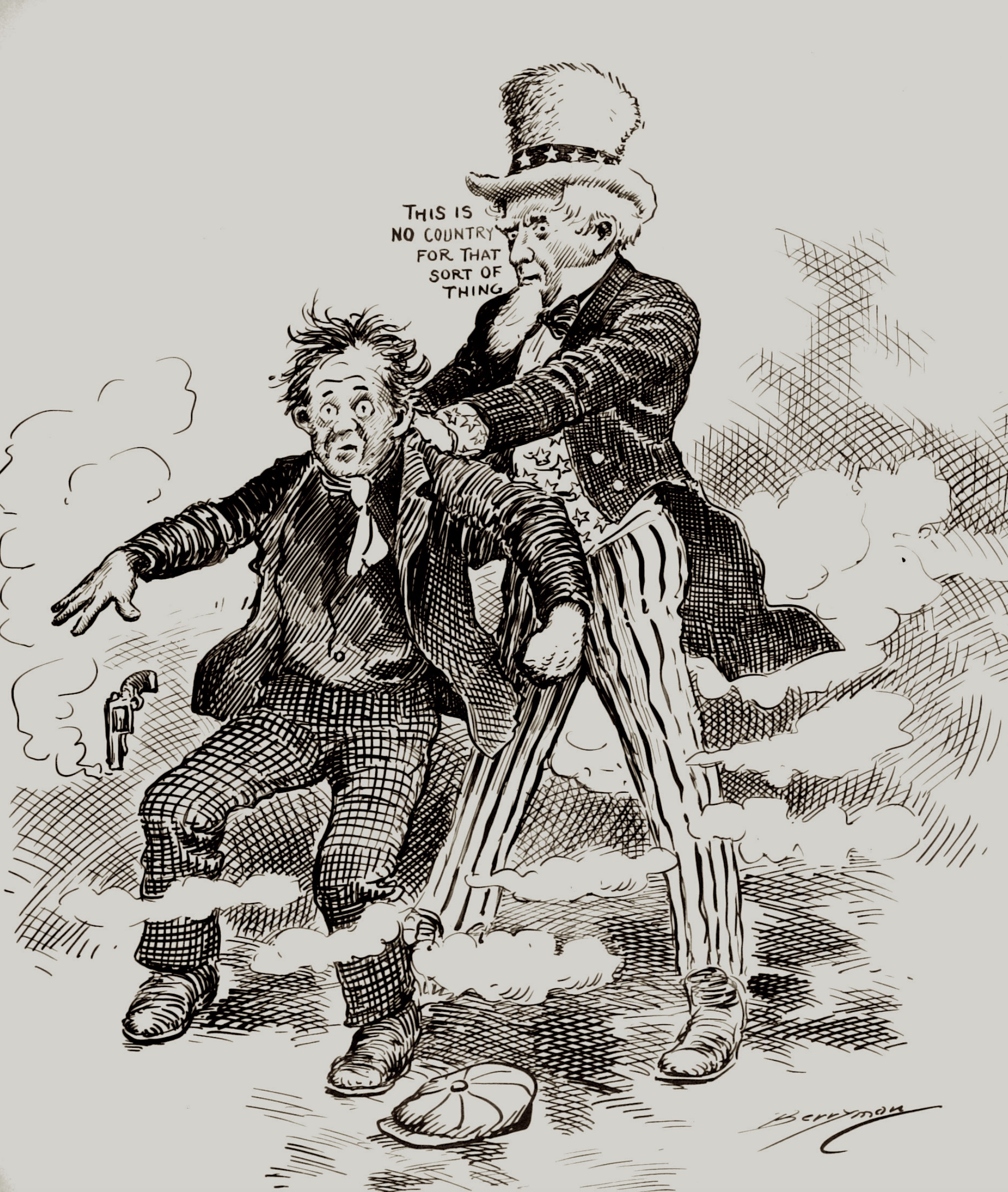

The Washington Evening Star published this cartoon by Clifford Berryman less than twenty-four hours after the shooting. The rapid transmission of news photographs from Milwaukee and Chicago, including a photograph of Schrank, enabled Berryman to draw an accurate likeness of the would-be assassin.

Roosevelt remained on the stage that night because he believed he had at least a chance to defeat Woodrow Wilson. Despite all of the ways in which the campaign of 1912 was modern, the candidates had no objective tools for assessing their competitive success. Systematic polling, which now dominates electoral politics, was a generation away. The New York Herald and a few other newspapers conducted informal surveys in 1912 but these were not at all reliable. The candidates and campaign operatives could only guess at how they were doing.57

A modern pollster could have told Roosevelt that he would win a large share of Republicans and some progressive Democrats, but that he would fall short of Wilson’s popular vote in most states and lose the electoral contest to Wilson in a landslide. This was as certain as anything could be as Roosevelt stood on the platform in the magnificent new Milwaukee Auditorium with a bullet in his chest, delivering one of the most dramatic speeches of his career. But no one knew it.

“I never was so boss-ruled in my life”

Roosevelt left the auditorium and went directly to Johnston Emergency Hospital, where doctors examined, cleaned, and bandaged his wound and had an x-ray made of Roosevelt’s chest. They concluded that he was in no immediate danger and could go on to Mercy Hospital in Chicago that night. Doctors there decided to leave the bullet where it was — that it posed no risk except a risk of infection which would be greater if they probed around in his chest to remove it.58

Members of Roosevelt’s campaign staff met with the press outside Mercy Hospital on October 15: (from left) O. K. Davis (holding papers in each hand), Charles Duell, Jr. (looking toward the hospital), Cecil Lyon (looking down), Philip Roosevelt, Elbert Martin, Dr. Scurry Terrell, and Henry Cochems. Martin is holding Roosevelt’s bullet-pierced speech. The man behind Cochems may be John McGrath. Chicago Daily News Collection, Chicago History Museum

They kept him under observation for six days, during which Edith Roosevelt, who rushed to Chicago, oversaw his care, intercepted all incoming mail, and kept visitors out. “This thing about ours being a campaign against boss rule is a fake,” Roosevelt complained. “I never was so boss-ruled in my life as I am at this moment.” The former president managed to sneak reporters in while “the boss” was sleeping in another room. “I’m not in such bad shape as you might think,” he told them. “My rib is broken, but if the edges can get together so that I can breathe a little easier, I can talk, and if that happens I intend to make more speeches in this campaign.”59

Martin and McGrath showed Roosevelt’s eyeglasses case to a news photographer in Chicago on October 15. The case is now in the collections of Theodore Roosevelt Birthplace National Historic Site in New York. Chicago Daily News Collection, Chicago History Museum

Over Roosevelt’s objections Taft and Wilson suspended their campaigns while the former president’s condition remained in doubt. Taft did so without hesitation. Wilson did so with some reluctance after his advisor Edward House wrote that if Wilson continued to speak he would create sympathy for Roosevelt and do his own campaign irreparable harm. Suspending the campaign, House told Wilson,, was “the generous, the chivalrous, and the wise thing to do.” The shooting also roused House to the risks Wilson was taking. He sent a short telegram to Bill McDonald, a former Texas Ranger, to come to New York to serve as Wilson’s bodyguard: “Come Immediately. Important. Bring your artillery.”60

Meanwhile Roosevelt’s detractors circulated stories that the shooting was a hoax — that the whole thing had been staged, that Schrank had been hired by Roosevelt and would soon be released, and that the bullet had been made out of wax. Roosevelt laughed at these conspiracy theories and joked with reporters that the Democratic candidate for vice president, Thomas Marshall, would soon be saying that the bullet hit someone else or that Roosevelt wasn’t even in Milwaukee that night.61

Speculation about how voters would react began as soon as the initial shock had passed. “That the American people are sentimental is generally admitted,” one editor wrote:

all civilized people are sentimental. And to argue that this shooting incident will have no effect on the vote is more or less absurd. It will affect the vote in the west, in the east, and possibly in the south; but less in the south than elsewhere. Some think that hundreds of thousands of votes will be changed; but as to that there is no telling. It is only reasonably safe to say that many people who previously had no idea of voting for the colonel will be drawn to him as the result of his conduct in connection with that cowardly bullet.62

Perhaps this was so, but there was no reliable way to assess how the shooting would shape the outcome of the election. Newspapers of every political orientation praised Roosevelt’s courage, but whether courage could turn the election was more than anyone could say.

Cecil Lyon and Philip Roosevelt watched over Roosevelt as he left his private car on October 22. The train stopped at nearby Syosset to avoid the crowd waiting at the Oyster Bay station. Library of Congress

Roosevelt left Mercy Hospital early on October 21, taking a side exit to avoid the spectators crowded around the main entrance. As if to suggest how much the need for secure would change campaigning for the presidency, the assistant police chief detailed thirty policemen in cars to accompany Roosevelt and his party to the train station. Ten more policemen on motorcycles led the motorcade. Dozens of detectives and plain clothes officers lined the route from the hospital to Union Station, watching, the press reported, for “cranks who might cause a repetition of the attempted murder of the colonel at Milwaukee.”63

Thousands of well-wishers hoping for a glimpse of the former president packed train stations across Indiana and Ohio, but Roosevelt was in no condition to venture on to the observation platform to wave to them. When the train reached Pittsburgh he confessed that he was “tired out.” Several hundred people gathered in the Altoona train station where the train stopped briefly after midnight. Word passed that Roosevelt was sleeping and the crowd was quiet until the train left. Roosevelt reached Sagamore Hill around 10:30 that morning, utterly exhausted.64

Sagamore Hill had no routine security guards, so the family recruited local oystermen and hired hands to guard the estate. They remained all day, but at dusk Roosevelt insisted they go home. He said he did not need any protection. He sent the doctors away as well but accepted their advice — which Mrs. Roosevelt would not have permitted him to ignore — that he spend the week recuperating. He saved himself for one final effort: the National Progressive Party Assembly in Madison Square Garden on October 30.65

On October 30, 1912, Madison Square Garden was filled to capacity for Roosevelt’s first public appearance since the shooting in Milwaukee. The bright calcium light shining on the stuffed bull moose was turned to Roosevelt when he began his speech. Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard University

As a political spectacle the rally had few rivals that year. Flags and bunting covered the walls and ceilings as well the speaker’s platform. From one side of the vast auditorium a large stuffed bull moose, illuminated by a bright spotlight, presided over the event from a platform of its own. A band struck up popular tunes and movies of Roosevelt played their light on a large screen on the back of the speaker’s platform while something like 17,000 people filled the arena.

Senator Joseph Dixon called the assembly to order at 8:30 p.m. He introduced the dignitaries on the platform — including Elbert Martin, bright with fame for having saved Roosevelt’s life. Oscar Straus, candidate for governor, and Hiram Johnson spoke. The people applauded at all the right moments, but they had come to see and hear Theodore Roosevelt and to cheer for him and celebrate that he had been spared.

It was nearly 9:30 p.m. when he entered the arena. Cheering rolled like a wave through the room even before people caught sight of him. He threw his broad smile to the audience as he climbed the stairs to the platform, waving with his left hand — carefully, a reporter thought — and then walked across the platform “with all his oldtime vigor.” The noise was deafening. For a moment Roosevelt stood beside Martin while the cheering continued, and then he paced the platform, alternately smiling broadly and frowning in a theatrical way as if to say enough.

The noise only grew louder. People stomped on the floor and stood on their chairs and cheered. When the band struck up Irving Berlin’s “Everybody’s Doin’ It,” they sang, yelling out their favorite line, “He’s a bear, he’s a bear, he’s a bear” and then the bouncy “We Won’t Go Home Till Morning,” which made Roosevelt laugh, and finally “Onward Christian Soldiers.” Roosevelt went back and forth on the platform, pointing to people on the floor, bouncing his left hand in time to the music. The demonstration went on for forty minutes.66

Finally Roosevelt spoke: “Friends, my friends, friends . . .” With those few words he silenced the crowd. “Friends,” he began, “perhaps once in a generation, perhaps not so often, there comes a chance for the people of a country to play their part wisely and fearlessly in some great battle of the age-long warfare for human rights. . . .”67

“I did not care a rap for being shot! It is a trade risk”

When the votes were counted on November 5, Woodrow Wilson was elected president. Wilson won less than forty-two percent of the popular vote — fewer votes than Bryan won in 1908 — but it was more than enough. He took forty of the forty-eight states and buried his opponents in an electoral landslide. Roosevelt won twenty-seven percent of the popular vote and six states, and Taft won twenty-three percent and just two states. Debs took six percent of the popular vote — the best showing for a Socialist candidate in our history.

Millions of Americans admired Roosevelt’s courage, but it’s not clear that it earned him many votes he wasn’t going to get anyway. He took Pennsylvania, Michigan, Minnesota, South Dakota, Washington, and California. Except for California, which Roosevelt won by just 174 votes out of 677,944 cast, these were states he expected to win. Roosevelt lost Illinois, which he had expected to carry, by fewer than 20,000 votes out over 1 million cast.

In Wisconsin, which he had fought so hard to win, he lost badly. Wilson won 164,228 votes there, Taft 130,695, and Roosevelt only 62,450. Debs polled 33,481 votes in Wisconsin. Wilson won Milwaukee with almost thirty-nine percent of the vote. Debs won almost twenty-seven percent of the votes in Milwaukee and Roosevelt just twenty-five. His total vote in Milwaukee County was just 5,939 — fewer people than heard him speak in the city auditorium with a bullet in his chest. The inescapable conclusion is that many LaFollette loyalists voted for Wilson. Roosevelt failed in Wisconsin. And despite all the excitement in Madison Square Garden, he came in third in New York.

A large crowd packed the train yard in the Ozark town of Monett, Missouri — a town of four thousand people — to see and hear Roosevelt. Wilson won solidly Democratic Missouri with forty-seven percent of the vote. Roosevelt came in a distant third. Frisco Archive

Never had a candidate with such a large popular following campaigned so hard and achieved so little. Roosevelt was tireless, intelligent, and creative. He was an accomplished writer and an engaging speaker. He had a remarkable rapport with reporters and a personal touch with ordinary people. His followers adored him. He was just fifty-four — the youngest candidate for the presidency in 1912 — and still had enormous energy. But he had been on the national stage for many years, and at one time or another had pursued policies that alienated many Americans. The larger-than-life personality that drew so many people to him repelled others, and by 1912 most Americans had made up their mind about him. In hindsight it seems that no campaign he might have waged in 1912 — even one in which he defied and cheated death — could have won him many more votes.

None of this was clear in the weeks after the election, during which there was a great deal of second guessing, frustration, and recrimination among Progressive leaders. Roosevelt congratulated Wilson but privately expressed his anger at LaFollette and others who had failed the common cause. But his greatest frustration was with “the great mass of ordinary commonplace men of dull imagination who simply vote under the party symbol and whom it is almost as difficult to stir by any appeal to the higher emotions and intelligence as it would be to stir so many cattle.”68

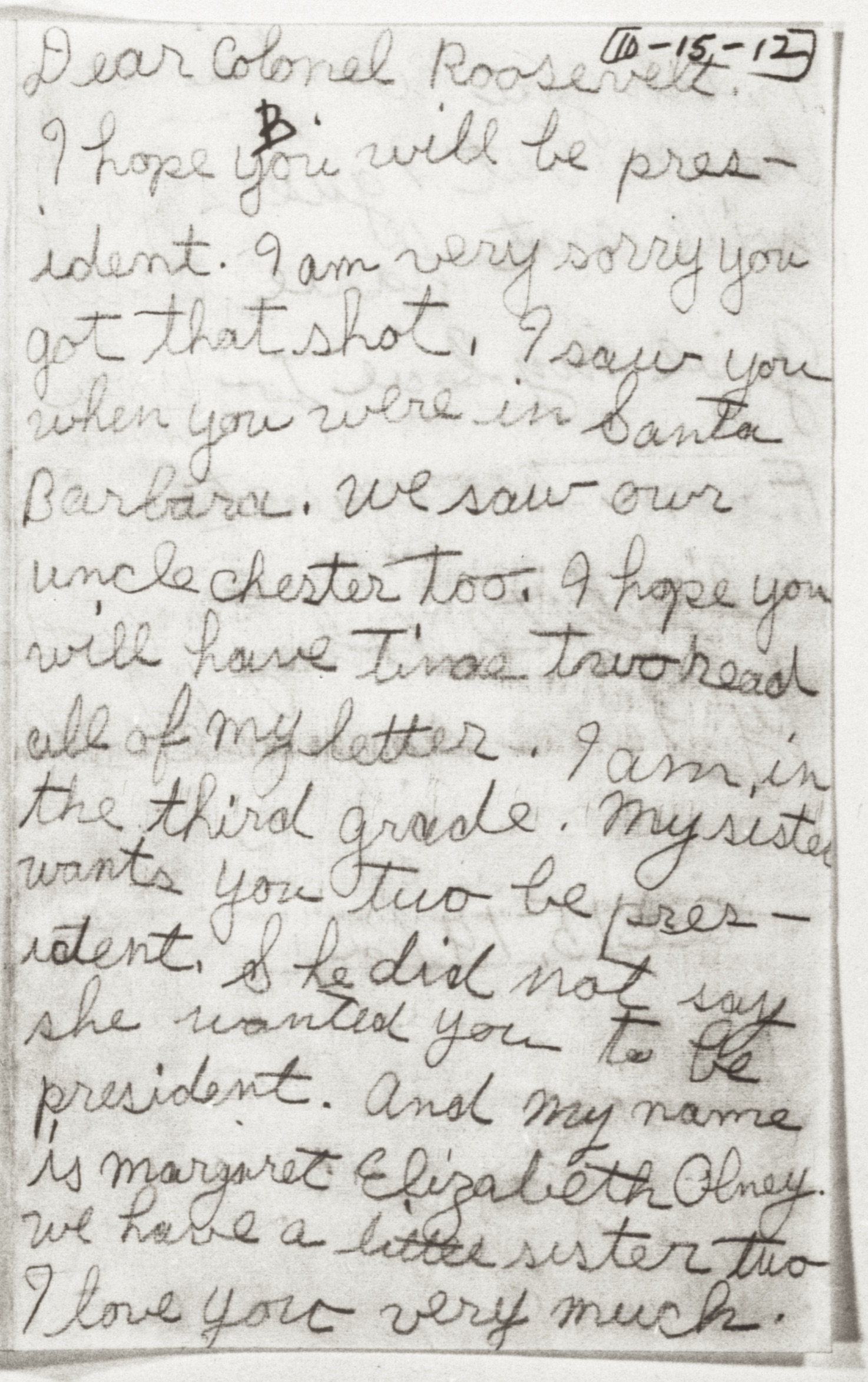

Among Roosevelt’s admirers was nine-year-old Margaret Olney, who wrote to him from California the day after the assassination attempt to say “I hope you will be president. I am very sorry you got that shot.” Theodore Roosevelt Papers, Library of Congress

This, we know, is entirely characteristic of modern presidential elections, in which candidates compete to win the votes of uncommitted voters in swing states and recognize that their opponents enjoy the support of an immovable base of party loyalists. But this was not so clear in 1912, when presidential elections as we know them were just beginning and candidates had no reliable way to identify uncommitted voters or swing states and no way to assess their own effectiveness. Roosevelt had no party organization on which to depend. He relied on his personal popularity and his formidable reservoir of talent and energy, but these were not enough. He campaigned blindly, appealing for votes in places he could not win and spending too much time in places he was likely to win or that weren’t worth the effort. In the process he exposed himself to enormous risks. His staff worried that someone would try to kill him and did what they could do to protect him. That a deranged man found an opportunity to shoot him is no surprise.

After the election Roosevelt wrote to his friend Sir Arthur Cecil Spring Rice: “I did not care a rap for being shot! It is a trade risk, which every prominent public man ought to accept as a matter of course.” With regard to Schrank, Roosevelt wrote that “I have not the slightest feeling against him. I have a very strong feeling against the people who, by their ceaseless and intemperate abuse, excited him to the action.” Roosevelt believed the shooting had been encouraged by the hostile rhetoric of his critics. In this regard he was much like supporters of former president Trump, who suggest that the malice of his would-be assassin was stoked by charges that Trump is a threat to democracy, an “existential threat” to the country, a fascist, or worse.69

At his arraignment Schrank pleaded guilty, saying “I shot Theodore Roosevelt because he was a menace to the country. He should not have a third term. . . . I shot him as a warning that men must not try to have more than two terms as President.” The judge referred Schrank to a group of five psychiatrists who examined him and considered all of the available evidence, including a scrap of paper found in Schrank’s pocket after the crime. Dated September 15, it was addressed “to the people of the United States.” It read: “in a dream I saw president McKinley sit up in his coffin, pointing at a man in a monk’s attire in whom I recognized Theo. Roosevelt. The dead president said This is my murderer, avenge my death.”70

The psychiatrists reported to the court that Schrank was insane. In private Roosevelt rejected that conclusion. “He was not really a madman,” Roosevelt wrote. “He was a man of the same disordered brain which most criminals, and great many non-criminals, have. I very gravely question if he has a more unsound brain than Eugene Debs.” Roosevelt was generally skeptical about the insanity defense and was contemptuous of “the mushy people” who would excuse Schrank because he was weak minded.71

Shrank was nonetheless diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia and committed to an asylum. He demanded that his pistol be put on display at the New-York Historical Society, revealing his wish, like that of many would-be assassins, to be remembered. He died in the asylum thirty-one years later, never having had a single visitor. Roosevelt carried Schrank’s bullet in his chest for the rest of his life. He told an old Harvard classmate “I do not mind it any more than if it were in my waistcoat pocket.”72

Notes

- On Garfield’s assassination, see Candice Millard, Destiny of the Republic: A Tale of Madness, Medicine, and the Murder of a President (New York: Doubleday, 2011). [↩]

- For a narrative account, see Scott Miller, The President and the Assassin: McKinley, Terror, and Empire at the Dawn of the American Century (New York: Random House, 2011); Though Czolgosz was determined fit for trial, psychiatrists who considered his case were not convinced. “Czolgosz was not a type frequently found in our public lunatic asylums,” one wrote, “but rather an aggravated specimen from the insane borderlands.” J. Sanderson Christison, “Epilepsy, Responsibility and the Czolgosz Case,” Kansas City Medical Index-Lancet vol. 23, no. 1 (January 1902), 10-17. [↩]

- Theodore Roosevelt to Henry Cabot Lodge, August 6, 1906, Joseph Bucklin Bishop, Theodore Roosevelt and His Time Shown in His Own Letters (2 vols., New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1920), 2: 22 (Bucklin’s work was republished as vols. 23-24 of The Works of Theodore Roosevelt (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1926) and is sometimes cited in that way). [↩]

- Robert Grant to James Ford Rhodes, March 22, 1912, James Ford Rhodes Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society. [↩]

- Theodore Roosevelt to Kermit Roosevelt, July 13, 1912, Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard University; Roosevelt’s task was made more difficult by the Socialist Party candidate Eugene Debs, who was making his fourth campaign for president. Debs had no chance of winning — he was engaged in party building — but he might draw enough votes to swing a close election. The campaign is ably summarized in Eugene Roseboom, A History of Presidential Elections (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1957), 358-74; for a more detailed narrative treatment, see James Chace, 1912: Wilson, Roosevelt, Taft & Debs — The Election that Changed the Country (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004). [↩]

- On Bryan’s whistle-stop campaigns, see Michael Kazin, A Godly Hero: The Life of William Jennings Bryan (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006), 67-68. [↩]

- Roosevelt often delivered this line as his train prepared to depart. It consistently produced a roar from the crowd. See Charles Willis Thompson, Presidents I’ve Known and Two Near Presidents (Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1929), 144-46. [↩]

- For an account of the campaign from the perspective of a reporter who traveled with Roosevelt, see Thompson, Presidents I’ve Known, 137-55. A New York Times reporter, Thompson offers useful insights about Roosevelt’s warm relationship with reporters, even those who worked for newspapers aligned with Roosevelt’s opponents. [↩]

- Oscar King Davis, Released for Publication: Some Inside Political History of Theodore Roosevelt and His Times, 1898-1918 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1925), [hereafter Davis, Released for Publication], 353. Duell was apparently included as a favor to his father, a New York lawyer Roosevelt had appointed to the federal bench. The elder Duell met with Roosevelt at Sagamore Hill on October 3. His son was twenty-three. He had dropped out of Yale before attending New York University law school but was not admitted to the bar until 1913, when he joined his father’s firm. His later career did him little credit. In 1914 the younger Duell sought Roosevelt’s endorsement of Charles Whitman for governor of New York. Roosevelt and other New York Progressives regarded Whitman with suspicion, and when it became clear Whitman had played Duell to gain Roosevelt’s support Duell was finished in politics. Roosevelt declined to help Duell secure an active duty post in the navy during World War I. Duell was subsequently involved in the movie business and had a scandalous relationship with Lillian Gish, whom he sued for breach of contract. The affair made him appear like a crass and spoiled opportunist, which he probably was. Davis made no mention of Duell in his book, nor does Duell’s name appear in most other accounts from the campaign. He was apparently an outsider who had little in common with the athletes and self-made men in the party. [↩]

- Thompson, Presidents I’ve Known, 173. [↩]

- “First Championship Game Taken by Wanderer Team,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 3, 1912, p. 2, reporting that McGrath “is easily the best right wing man who has been seen in local hockey circles in years.” McGrath never enrolled in law school. He served as Roosevelt’s secretary after the campaign and later managed a commercial fishing business. On Martin, see “Elbert E. Martin a Hero,” Chicago Tribune, October 16, 1913. [↩]

- Davis, Released for Publication, 361. [↩]

- Thompson, Presidents I’ve Known, 145-46; Theodore Roosevelt to Kermit Roosevelt, September 27, 1912, Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard University. [↩]

- On the incident in Saginaw, see “Elbert E. Martin a Hero,” Chicago Tribune, October 16, 1913; Davis, Released for Publication, 361-62. [↩]

- For LaFollette’s critique of Roosevelt’ candidacy, see Robert LaFollette, La Follette’s Autobiography: A Personal Narrative of Political Experiences (3rd ed., Madison, Wisconsin: The Robert M. La Follette Co., 1919), esp. 543-44, 672-75, 742-48. [↩]

- Davis, Released for Publication, 350-51, 399-400; on Cochems, see “Seeks Seat in Congress: Henry F. Cochems, Ex-College Athlete, After Republican Nomination,” The Lincoln Herald, Lincoln, Nebraska, September 14, 1906; Roosevelt had met with McGovern and Cochems in Milwaukee in March and secured their support for the Republican nomination; both men had supported a fusion of LaFollette and Roosevelt supporters in the Republican convention; see Robert LaFollette, Autobiography, 647-48. [↩]

- “T.R. Defends His Record on Tariff,” The Argus, Albany, N.Y., October 12, 1912, p. 1. [↩]

- Passenger service between Chicago and Milwaukee on the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway in 1910 varied between 2 hours for express service and 2 hours 55 minutes for local service; The Chicago Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway — Passenger Train Schedules (Corbitt Railway Printing Co.: Chicago, September 1910); Wheeler Bloodgood and a committee of Wisconsin Progressives rode the train from Chicago; Davis reported that the train made several whistle stops and took about 3 hours to reach Milwaukee; for a first-hand description of the stop in Racine, see Eugene Walter Leach, “Attempted Assassination of Theodore Roosevelt,” Racine Journal, August 13, 1921. Leach, finance chairman of the Progressive Party in Racine County, boarded the train at Kenosha with J. M. Jones and Congressman Henry Cooper, and recalled that University of Chicago political science professor Charles Merriam made remarks there from the back of the train while Roosevelt, saving his voice, waved to the crowd and shook hands. In Racine Cooper made remarks and Roosevelt, against the advice of his staff, began to speak, but stopped when the train pulled out of the station. Leach wrote his account in late 1912 but it was not published until 1921; on the discussion about whether Roosevelt should stay in the railroad car or go to the hotel, see Statement of Wheeler P. Bloodgood, Oliver E. Remey, Henry F. Cochems, and Wheeler P. Bloodgood, The Attempted Assassination of Ex-President Theodore Roosevelt (Milwaukee: Progressive Publishing Company, 1912) [hereafter Attempted Assassination], 134-35, and Davis, Released for Publication, 371-72; Girard testified at Schrank’s trial that he had known Roosevelt about twenty-five years. He had served as Roosevelt’s bodyguard in the past, and in 1912 was living in Milwaukee; Transcript of Trial, 23. [↩]

- See, e.g., “When Teddy Roosevelt took a bullet in Milwaukee and then gave a speech,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel (online), June 2, 2020, which leads with a photograph of Roosevelt greeting supporters standing in a car identified in the caption as a photograph taken on October 14, 1912, “shortly before a gunman shot and wounded him in front of the Gilpatrick Hotel.” Other publications have since identified this as a photograph taken at the hotel moments before Roosevelt was shot, which it clearly is not. The building in the background is not the hotel; the car is not the right sort; Roosevelt is not wearing an overcoat, as he was when he was shot, and the photograph was taken in daylight — it was night when Roosevelt was shot. The Journal Sentinel article conflates Roosevelt’s September visit, when this photograph was probably taken, and his October 14 campaign stop. Gerard Helferich makes a similar error, describing a photograph of Roosevelt leaving the Milwaukee train station taken in September as if it was taken on October 14; Helferich, Theodore Roosevelt and the Assassin, 169-70. [↩]

- Davis, Released for Publication, 373. [↩]

- Wheeler Bloodgood, Wisconsin’s representative on the national party committee, and a group of Progressive leaders came in the lobby about the time Roosevelt’s party went upstairs. They had arrived in a car which was parked outside behind the car waiting for Roosevelt. Bloodgood told Girard to use the car for Roosevelt’s staff and walked the three blocks to the auditorium. Statement of Wheeler Bloodgood, Attempted Assassination, 136. [↩]

- Gerard Helferich does an admirable job reconstructing Schrank’s depressing life and his pursuit of Roosevelt in Theodore Roosevelt and the Assassin: Madness, Vengeance, and the Campaign of 1912 (Guilford, Connecticut: Lyons Press, 2013). [↩]

- The challenge of reconstructing the assassination attempt is very similar to the challenge of reconstructing the Boston Massacre, which also took place on a dark street, involved scores of people, and lasted only a few minutes. See “Lessons from the Boston Massacre.” [↩]

- Davis, Released for Publication, 383, reports that “not one of the correspondents with our party had been present when the shot was fired.” While Roosevelt was speaking Davis left the stage and met with them to describe the shooting and answer their questions but since Davis had not been present either the headline stories published in newspapers the next day were riddled with mistakes. [↩]

- Attempted Assassination [see note 18 above]; State of Wisconsin vs. John Schrank, November 12, 1912, Trial Transcript, John F. Schrank Municipal Court Records, Milwaukee Public Library [hereafter Trial Transcript]. [↩]

- Philip Roosevelt later wrote an unpublished, 61-page account of the campaign “Politics of the Year 1912: An Intimate Progressive View.” It is in the Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard University. The manuscript is not dated; Roosevelt died in 1941. Martin’s remarks to the press are in “Elbert E. Martin a Hero,” Chicago Tribune, October 16, 1913, p. 4; After the campaign Martin went to work for the opulent new Vanderbilt Hotel on Park Avenue in New York, ultimately as assistant manager. In 1934 he moved to Vermont, where he served in the state legislature (1943-53) before returning to Detroit (“Given Party,” The Brattleboro Reformer, June 15, 1953, p. 4; Obituary, ibid., September 13, 1956) where he practiced law briefly before moving to Idaho to be near his only child, Helen Martin Higby (b. 1912). Some time in this odyssey he wrote his account. Internal evidence suggests that Martin referred to Davis’ book, Released for Publication, which was published in 1925, so Martin probably wrote (or at least finished) his account after that year. Martin described the conversation among the group in Roosevelt’s car in almost exactly the same words used by Davis, though Martin was walking beside the car and cannot have heard the conversation very clearly over the noise of the crowd and the car engine (for another hint that Martin relied on Davis, see note 33 below). Martin’s daughter preserved his typescript and provided it to Beverly Brown Grabow (1932-2014), a Utah history teacher who used it to write “Assassin and Hero: The Making of Men — A New Analysis of the Attempted Assassination of Theodore Roosevelt” (master’s thesis, Utah State University, 1973). Mrs. Grabow included a photocopy of the typescript as an appendix to her thesis, otherwise it might have been lost. She refers to it as the text of a speech but does not say when it was written or where and when the speech was delivered. It seems likely that Mrs. Higby told her it was written as a speech. [↩]

- Oscar King Davis to George Perkins, October 15, 1912, is in the collection of Roosevelt biographer Edmund Morris. He used it as a source for his brief narrative of the shooting in Colonel Roosevelt (New York: Random House, 2010), 243-48; Oscar King Davis, “Roosevelt’s Marvelous Escape from Death,” Munsey’s Magazine, vol. 48, no. 4 (January 1913), 606-9; Davis, Released for Publication (see note 9 above). [↩]

- This man’s name is variously rendered. Martin refers to him as “Lettish” which may be how he said his name (Narrative, 2). Edmund Morris refers to him as Fred Leuttisch (Colonel Roosevelt, 243); Davis calls him Fred Luettich (Davis, Released for Publication, 374). Luettich is how his name is spelled in the 1920 census and in the record of his death in Cook County, Illinois, in 1938. He was thirty-five at the time of the shooting. [↩]

- The make, model, and year of the car in which Roosevelt rode is not identified in the sources, but from the photograph of it published in Attempted Assassination (p. 90) it appears to be a 1912 Rambler Country Club. The Rambler was made in Kenosha, Wisconsin, and would later be known as the “Kenosha Cadillac.” Among the distinguishing features of the 1912 Rambler was a raked windshield — most cars of the period had vertical windshields. The make, model, and year of the second car is not documented in the available sources but it played no role in the event. The second car had been left for Roosevelt’s party by Wheeler Bloodgood a few minutes before eight. Presumably King, McGrath, and Dr. Terrell would have gotten into it if they had come downstairs with the others. [↩]

- That Philip Roosevelt was preparing to follow Martin into the car was Martin’s recollection (Martin, Narrative, 2); Davis, Released for Publication (p. 374) says that the young Roosevelt was getting in ahead of Martin when the shot was fired, but since Martin was present his recollection is more reliable. [↩]

- Martin, Narrative, 2. [↩]

- Statement of A. O. Girard, Attempted Assassination, 141-42. [↩]

- Statement of Thomas Taylor, Attempted Assassination, 147; Statement of Frank Buskowsky, Attempted Assassination, 149-50. [↩]

- For Murray’s testimony, see Trial Transcript, 31; Statement of Henry F. Cochems, Attempted Assassination, 16, says that Martin, Girard, “and several policemen” subdued Schrank; he probably did not know Murray by name; Girard says that he, Martin, and Murray subdued Schrank. Oscar Davis, who ran downstairs as soon as he heard the shot, did not reach the scene before Schrank was subdued. Reconstructing what happened from first-hand reports, Davis confused Girard for Fred Luettich, the doorman from Progressive Party headquarters in Chicago, and wrote that Luettich had leapt on to Schrank following Martin. Davis made no mention of Girard in his account and seems to have been generally unaware of his role; Davis, Released for Publication, 375. Attempted Assassination makes no mention of Luettich nor was he mentioned at Schrank’s trial. Luettich undoubtedly returned to Chicago with Roosevelt late on the night of the attempted assassination. He was probably unknown to those who remained in Milwaukee. Martin also confused Luettich for Girard in his typescript. He may have remembered it that way or he may have used a copy of Released for Publication to fill in the gaps in his knowledge, suggesting the possibility that Martin’s surviving typescript was completed no earlier than 1925; Martin, Narrative, 2. [↩]