History intrudes continuously on public life. How we react reflects how we think about ourselves as much as what we think about our past.

History intruded on presidential politics at a town hall meeting in New Hampshire last December when a man asked Nikki Haley, “What was the cause of the Civil War?” She stumbled through her answer, trying to escape history and pivot to the present. “I think the cause of the Civil War was basically how government was going to run, the freedoms and what people could and couldn’t do. . . . I think it always comes down to the role of government and what the rights of the people are. And I will always stand by the fact that I think government was intended to secure the rights and freedoms of the people. It was never meant to be all things to all people. Government doesn’t need to tell you how to live your life. They don’t need to tell you what you can and can’t do. They don’t need to be a part of your life.”

It was a confused mashup, suggesting that the Civil War was caused by a conflict between big government statists infringing on freedom and small government conservatives — the kind of voters she was courting — except in 1861 many small government conservatives wore gray and owned slaves. The man who asked the question expressed surprise that she hadn’t mentioned slavery.

The next day she did the obligatory damage control. “Of course the Civil War was about slavery,” she said on a New Hampshire radio show. “We know that. That’s the easy part of it.”

There’s really no easy part here. What something is “about” and its cause are not the same — President Biden (or his campaign staff on his behalf) made the same mistake, posting “It was about slavery” on social media. The Civil War was about many things — sectional differences, the preservation of the Union, the failure of politics to resolve conflicts, the future of the West, the rising importance of industry and commerce relative to agriculture, and the conditions of labor — in addition to the status of slavery and the rights of the enslaved.

Causation, about which there is a rich philosophical debate, is no easier. For most historians causation is a contingent relationship in which an event is dependent on the influence of an antecedent distinct from itself. That definition doesn’t satisfy scientists or many philosophers, who look for cause and consequence to be predictable and repeatable.

In history they never are. Historians cannot conduct experiments and history, despite the clichés, never repeats itself. It is a science of single instances, which is not a science at all. Bertrand Russell, who regarded the idea of causation with skepticism, explained that once a cause is specified so fully that its effect is inevitable, it is extremely unlikely that the cause occurs more than once.1

So it seems to have been with our Civil War. The pundits enjoyed skewering Haley for not saying slavery caused the Civil War but slavery didn’t cause the Civil War. It wasn’t the match that set off the explosion. Slavery had existed for thousands of years. It was not the cause of the war nor a catalyst. It was a precondition, upon which the cause did its work.

That cause was principled, unyielding insistence that slavery was an evil in the sight of God, contrary to the ideals of the American Revolution, and must end — immediately, unconditionally, and without compromise. Slavery didn’t cause the Civil War. Abolitionism did.

II

Slavery was an inherited evil, contrary to the ideals of liberty, equality, natural and civil rights, and citizenship that defined the American Revolution. The framers of the Federal Constitution accommodated slavery while holding it at arm’s length — recognizing the inescapable reality that it was foundation of the southern economy but refusing to give it an explicit sanction. Optimists in the Federal Convention believed, or at least believed there were grounds to hope, that slavery would wither if the slave trade was ended and that alternative crops would break slavery’s hold on the economy.2

That the optimists were wrong — that slavery would spread with the cultivation of cotton, a crop of little importance in 1787 — does not invalidate their accomplishments. Their generation challenged a practice that was as old as mankind, passed laws to abolish it in the northern states, and articulated ideals that shaped the long campaign to abolish slavery throughout the country. Abolition in the northern states dramatically increased the nation’s free black population, from which emerged a generation of articulate spokesmen for emancipation. Eloquent black abolitionists like Frederick Douglass, who escaped slavery at twenty, disabused northern audiences of the idea that the enslaved were content or fit only for brute labor.3

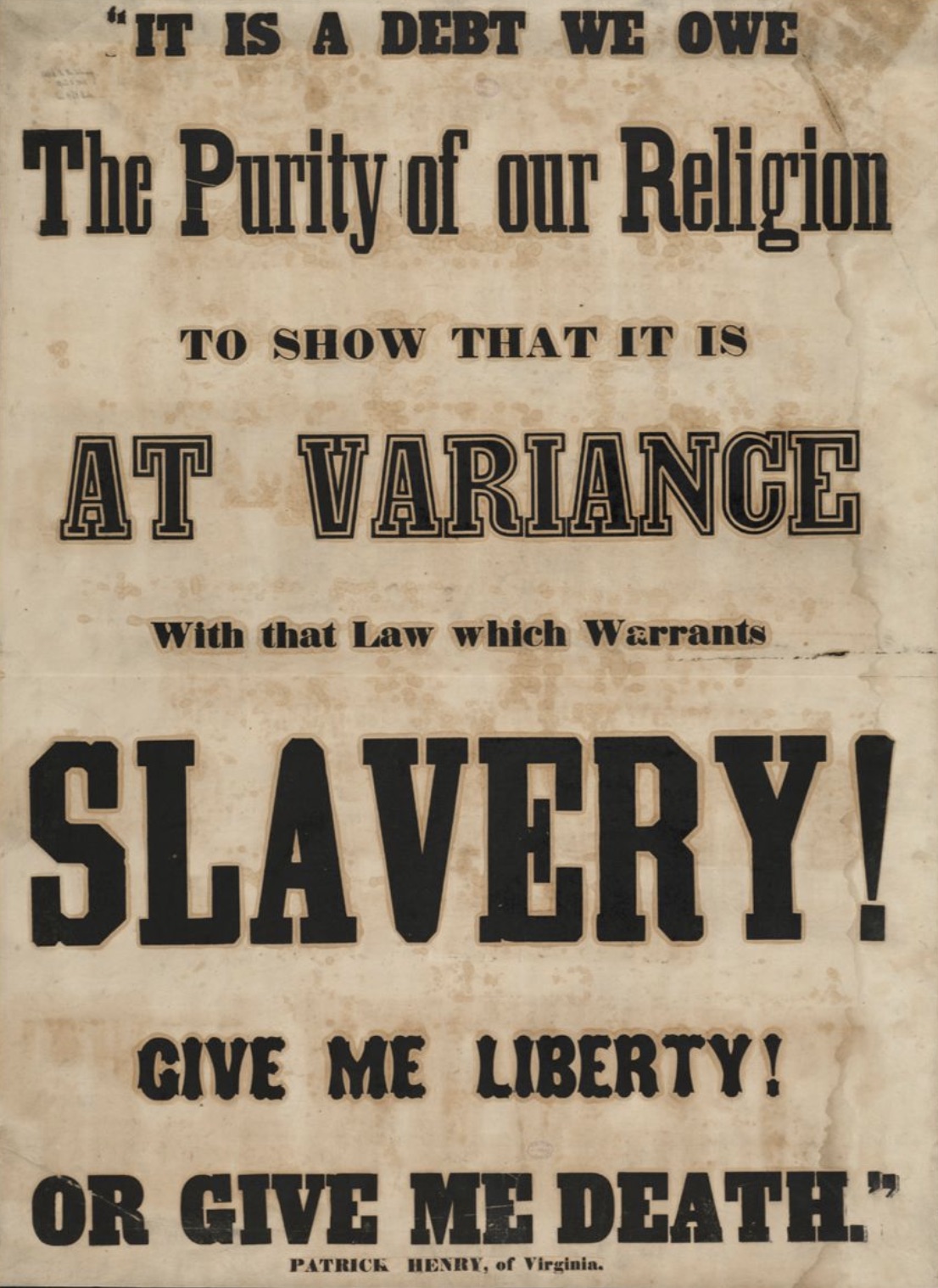

This broadside, published about 1857, links abolitionism with Christianity and the idealism of the American Revolution. Boston Public Library

Opposition to slavery grew in the first decades of the nineteenth century, but the motives and aims of slavery’s opponents varied considerably. Many opposed slavery because of its violence and inhumanity, others because it was inconsistent with the principles of the American Revolution, and still others because they were convinced that a society composed of people of different races was impractical. Most believed that slavery was inconsistent with the gentle teachings of the New Testament that were central to the religious revivals of the early nineteenth century.

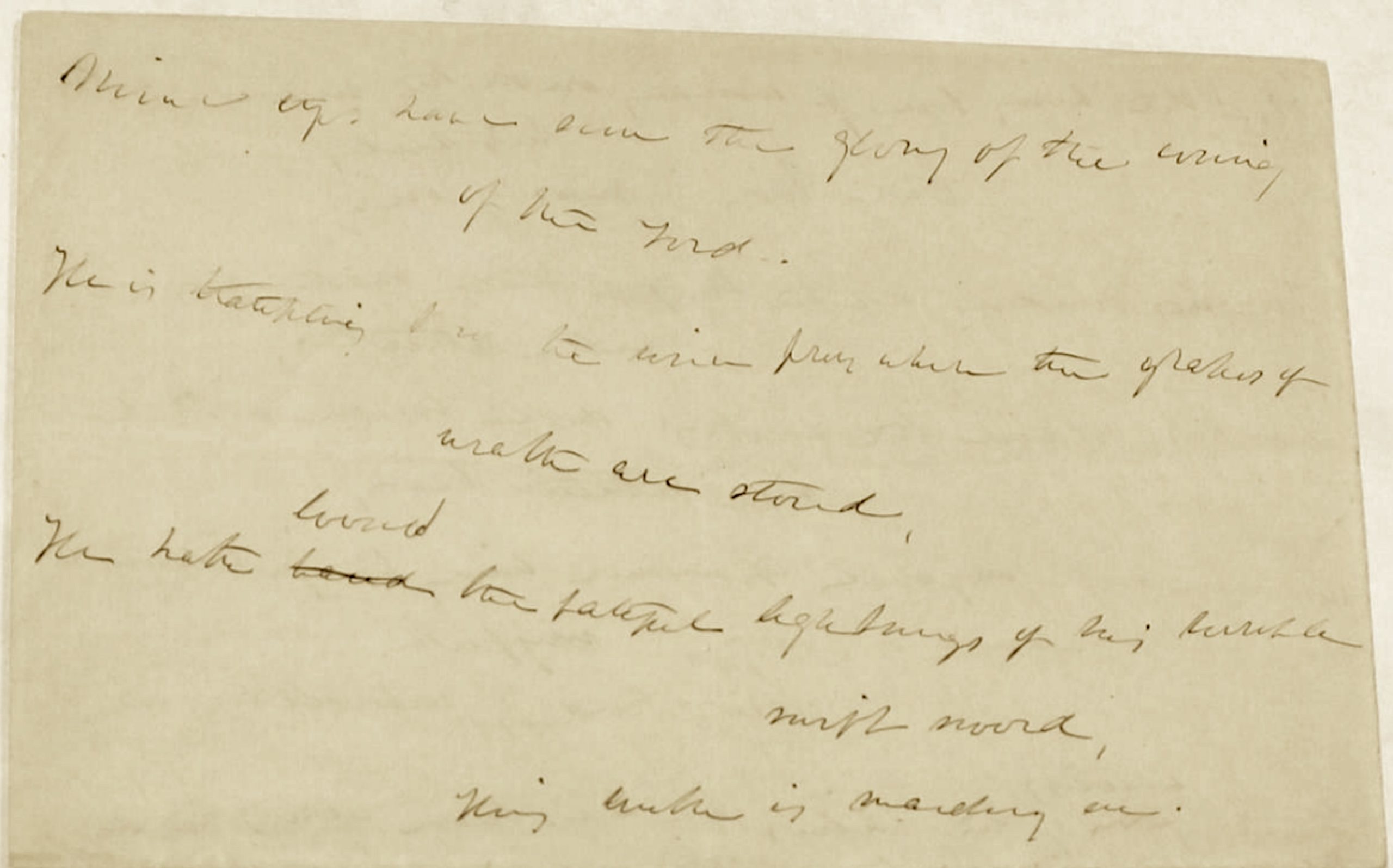

Those revivals shaped the antislavery movement and made it, for many, a religious crusade. It is not a coincidence that the most enduring reminder of the antislavery movement is a hymn. The words came to Julia Ward Howe on the night of November 18, 1861, after she watched a procession of Union soldiers. She remembered that she

awoke the next morning in the gray of the early dawn, and to my astonishment found that the wished-for lines were arranging themselves in my brain. I lay quite still until the last verse had completed itself in my thoughts, then hastily arose, saying to myself, I shall lose this if I don’t write it down immediately. I searched for an old sheet of paper and an old stub of a pen which I had had the night before, and began to scrawl the lines almost without looking, as I learned to do by often scratching down verses in the darkened room when my little children were sleeping. Having completed this, I lay down again and fell asleep, but not before feeling that something of importance had happened to me.4

Hastily written in the half light of dawn, the first draft of The Battle Hymn of the Republic differs little from the hymn we know. Julia Ward Howe later changed “He is trampling out the wine from which the grapes of wrath are stored” to “He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored.” Museum of the Bible, Washington, D.C.

She sent the poem to The Atlantic Monthly, which paid her four dollars. The editor gave it a title — The Battle Hymn of the Republic:

Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord:

He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored;

He has loosed the fateful lighting of his terrible swift sword:

His truth is marching on.

The fifth and final verse embodies the moral imperative of the abolitionist crusade:

In the beauty of the lilies Christ was born across the sea,

With a glory in His bosom that transfigures you and me;

As He died to make men holy, let us die to make men free,

While God is marching on.

The abolitionists demanded nothing short of immediate, unconditional, and universal emancipation — the end of slavery, without compromise. They were a minority among slavery’s opponents, most of whom were willing to end slavery by measured steps — ending the slave trade (which many, obtuse to natural increase, believed would lead the enslaved population to wither), liberalizing emancipation laws, and restricting and ultimately forbidding slavery in the nation’s western territories. To the abolitionists these half measures were compromises with the devil.

The majority of white Americans in the northern states were apathetic about slavery. They might regard it as an evil but it was an evil somewhere else, far removed from the pressures of daily life. They regarded abolitionists as troublemakers or worse — as incendiaries encouraging slave rebellion and the slaughter of whites like the murders Nat Turner and his followers committed in Virginia in 1831. In most of the United States an abolitionist speaker was apt to be driven out of town, stoned, or worse. Elijah Lovejoy, an abolitionist newspaper editor in Illinois, was murdered by a pro-slavery mob in 1837.

The tide turned for the abolitionists as a consequence of the political compromises that followed the Mexican War — particularly the Fugitive Slave Act, which required free state governments to cooperate in the return of runaway slaves. The ordinary white northerner was just as attached to his state as any southerner and many were hostile to this invasion of state sovereignty. The controversy drew attention to runaway slaves and what had become known as the Underground Railroad — a network of safe houses and northern “conductors” who helped slaves move north. In that moment Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which focused on the plight of the enslaved and the impulse to flee from slavery, created a sensation. It sold 300,000 copies in its first year and quickly became the bestselling American book of the nineteenth century.

In the political hothouse of the 1850s, the influence of the abolitionists grew dramatically. They won adherents through moral suasion and fueled the intransigence of slaveholders, who regarded themselves as besieged despite a succession of political and judicial victories. With each success of the slaveholders — the Fugitive Slave Act, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, the Dred Scott decision — the abolitionists grew louder, more determined, and more effective. Slaveowners grew more strident, more defensive.

Abolitionists were still a minority on the eve of the war, reviled in many quarters, but they included some of the nation’s most able writers and intellectuals and some of its most determined and effective politicians — an “army of talented and articulate reformers,” one of their most important historians, James McPherson, calls them, commanding “an audience and a notoriety far out of proportion to their numbers.”5 They also included millions of enslaved Americans — disfranchised and abused, but not powerless, as many thousands would demonstrate by taking up arms — and scores of black abolitionist leaders and spokesmen.

Over 200,000 black soldiers — abolitionists in arms — served in the Union army during the Civil War. Many were photographed, but this is the only known wartime photograph of a black soldier in uniform with his family. Library of Congress

The influence of the abolitionists was magnified by divisions among everyone else — between those who regarded slavery as a good thing, those who ignored its horrors while pursuing profit or political office, those inclined to accommodate slaveowners to preserve the Union, and the largest number, in the North, who were confused and uncertain and wished the whole problem would go away. Most transforming moments have been the work, ultimately, of determined minorities.

III

Critics remind us that the end of slavery was too long delayed — that for more than fourscore years the nation accommodated the grotesque injustice of slavery — and point to Britain, which managed to abolish slavery without war a generation before the United States. Some suggest that if the thirteen colonies had not fought and won a war for independence slavery would have ended with the 1833 act of Parliament abolishing slavery in the British empire.6

The evidence doesn’t lead to that conclusion. British abolitionism was inspired by the universal ideals of the American Revolution, as were the revolutions in France and Latin America.7 If the American Revolution had never occurred or had failed the course of liberal reform in the nineteenth century would probably have been quite different, if it occurred at all.

As it was the British abolitionists had an enormous advantage over their American counterparts. By the early nineteenth century West Indian sugar was no longer a source of vast new wealth. The economy of Britain and its empire had diversified — industry, commerce, and finance had overtaken staple crop agriculture — in ways that made it practical for the empire to do without slave labor.

The West Indian colonies where slavery was a central feature of economic life were not formally represented in Parliament, but the sugar barons long maintained political influence by buying seats in the unreformed House of Commons. They successfully blocked abolition until the Parliamentary Reform Act of 1832 eliminated the rotten boroughs and deprived them of political leverage.

In the United States, by contrast, cotton was spreading across the South and enriching planters, merchants, and textile manufacturers just as sugar had enriched West Indian planters and British merchants a century earlier. By 1830 there were more than 3.2 million enslaved people in the United States — four times as many as Parliament freed when it abolished slavery in the empire.

Whether British abolitionists could have convinced Parliament to free them all in 1833 — and compensate American slaveowners as they compensated West Indian planters — seems doubtful. The textile mills of the British industrial revolution depended on American cotton, but since the American South was not part of the empire, British abolitionists did not have to contend with cotton merchants, mill owners, and their representatives in Parliament, and Parliament did not have to worry about the economic consequences of depriving cotton planters of millions of enslaved workers.

The critical difference between the British empire and the United States in this regard was political: as cotton cultivation spread, the number of slave states and thus the political influence of slave-owning planters increased. For Parliament, slavery was a colonial problem largely isolated from domestic politics. For Congress, it was a national problem, and during the 1850s it shaped nearly every political issue, however remote they seemed from slavery.8

Parliament was no more virtuous than Congress. Emancipation took longer in the United States than it did in the British empire because the enslaved population in the United States was larger, cotton was more important to the American economy than sugar to the British economy, and because slaveowners enjoyed more influence in Congress than in Parliament.9

That slaveowners enjoyed so much influence in American government does not make our Constitution, as its loudest critics claim, fundamentally or “systemically” racist, except insofar as a political order based on principles of universal right empowers ignorant, bigoted, callous, selfish, and greedy people in the same way it empowers the wise and virtuous. Creating a truly free society requires overcoming layers of injustice, exploitation, and other forms of institutionalized oppression accumulated over many centuries, as well as eliminating the ignorance, bigotry, and greed that support them. Doing so has been among the costs of fulfilling the ideals of the American Revolution.

IV

What could be more clear?

Participants on both sides knew what caused the Civil War. The South Carolina Declaration of Secession explained that the state’s decision to leave the Union was the consequence of “an increasing hostility on the part of the non-slaveholding States to the institution of slavery” and the agitation of those who have “encouraged and assisted thousands of our slaves to leave their homes” while “those who remain have been incited by emissaries, books and pictures, to servile insurrections.” The South Carolinians added that “for twenty-five years this agitation has been steadily increasing, until it has now secure to its aid the power of the common Government.”10

Lincoln knew it, too. When Secretary of State William Seward introduced Harriet Beecher Stowe to the president in December 1862 Lincoln reportedly said “Why, Mrs. Stowe, right glad to see you! So you’re the little woman who wrote the book that made this great war! Sit down, please.”

Mrs. Stowe was touched by the president’s “rustic pleasantry,” but she had come with a serious purpose. “Mr. Lincoln,” she said, “I want to ask you about your views on emancipation.” He had spent many years as an antislavery compromiser, but in the end he surrendered to the moral imperative of freedom and became an abolitionist at last. He knew that the abolitionists had pressed the slaveholders to secession and the nation to war and that they had turned the war into a crusade to make men free.11

Why don’t we see it?

Perhaps because in their time the abolitionists were widely condemned as eccentrics and incendiaries — as self-righteous, moralizing busybodies or, like John Brown and his supporters, dangerous agitators who encouraged violence and rebellion — and that reputation clings to them even now. Perhaps because many Americans are uncomfortable with the absolute moral certainty that flowed from Christian convictions they do not share. We live, to our detriment, in a time of subjectivism when many Americans no longer believe in moral absolutes or if they do, they don’t have the courage to uphold their convictions. The abolitionists chastise us by example.

Perhaps we don’t see it because for the last generation we have been told that we should be ashamed of our nation’s past. Surely the man who asked Nikki Haley “what caused the Civil War?” was not expecting her to answer: “an uncompromising demand for freedom and a conviction that all men and women, everywhere, should be free.” But that’s the right answer.

Notes

- Bertrand Russell, On the Notion of Cause (London: Allen and Unwin, 1918). [↩]

- On the Federal Convention, see particularly Sean Wilentz, No Property in Man: Slavery and Antislavery at the Nation’s Founding (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018); on the neutrality of Constitution with respect to slavery, see Don Fehrenbacher, The Slaveholding Republic: An Account of the United States Government’s Relations to Slavery, New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. [↩]

- On Douglass, see especially David Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018) and the scholarly edition of Douglass’ second autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), for which Professor Blight wrote the introduction and annotation. Our understanding of the abolitionist movement and its varied actors — white and black, men and women — has grown dramatically in the last generation. On women abolitionists, see Julie Roy Jeffries, The Great Silent Army of Abolition: Ordinary Women in the Anti-Slavery Movement (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998). [↩]

- Julia Ward Howe to J.C. Ridgway, May 21, 1892, RR Auction, September 23, 2023. See the online description. on the long, rich history of the song, see John Stauffer and Benjamin Soskis, The Battle Hymn of the Republic: A Biography of the Song that Marches On (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013). [↩]

- James McPherson, The Struggle for Equality: Abolitionists and the Negro in the Civil War and Reconstruction (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1965), 4. McPherson was referring to the radical Garrisonians, but his apt description applies to the abolitionists more broadly. For a fresh assessment of divisions among the Garrisonians during the war, see Frank Joseph Cirillo, The Abolitionist Civil War: Immediatists and the Struggle to Transform the Union (Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University Press, 2023). [↩]

- See, for example, in the popular press, Adam Gopnik, “We Could Have Been Canada,” The New Yorker, May 8, 2017. [↩]

- On the relationship between the American Revolution and the rise of the antislavery movement in Britain, see Christopher Leslie Brown, Moral Capital: Foundations of British Abolitionism (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006). [↩]

- This is a central insight of David Potter’s The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861 (New York: Harper & Row, 1976), still among the most important works on the decade preceding the Civil War. [↩]

- On the painfully slow end of slavery, Ira Berlin, The Long Emancipation: The Demise of Slavery in the United States (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015), is an excellent place to begin; Patrick Rael, Eighty-eight Years: The Long Death of Slavery in the United States, 1777-1865 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2015) puts the process in international context, distinguishes between metropolitan and colonial abolition, and recognizes the substantial role of black abolitionists in turning northern public opinion against slavery. [↩]

- For the text of the declaration, see John Amasa May and John Reynolds Faunt, eds., South Carolina Secedes (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1960), 76-81; On the declaration, see the commentary by Harry V. Jaffa in A New Birth of Freedom: Abraham Lincoln and the Coming of the Civil War (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2000), 230-35. [↩]

- The conversation was thus reported by her son and grandson, Charles Edward Stowe and Lyman Beecher Stowe, in Harriet Beecher Stowe: The Story of Her Life (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1911), 202-3. Their life of their mother and grandmother is generally sound and in the absence of further evidence about the conversation I am inclined to accept their account. Donald R. Vollaro is not. He calls the story “pseudo-historical flotsam” and has invested considerable effort trying to debunk it in “Lincoln, Stowe, and the “Little Woman/Great War” Story: The Making, and Breaking, of a Great American Anecdote,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, vol. 30, no. 1 (Winter 2009), 18-34. He has some interesting things to say, but ultimately his argument does not persuade me. The “Breaking” in his title is unmerited self-congratulation. Don Fehrenbacher, a great Lincoln scholar, properly described the story as an “unverified family tradition” (Don E. and Virginia Fehrenbacher, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1996), 428). Nothing in Vollaro’s lengthy examination invalidates the possibility that Harriet Beecher Stowe reported to her son Charles that the president had greeted her in this way. Vollaro attributes the story to the family’s desire (about which he cites no evidence at all) to attach greater importance to Uncle Tom’s Cabin than he thinks it deserves, citing critical contemporary reviews, which have nothing to do with the matter. The book sold 10,000 copies in its first week, 300,000 in its first year, and sold more copies in the United States, after the Bible, in the entire century. Vollaro seems to doubt that anyone was reading it or was much influenced by it. He shows his hand by suggesting that the book’s “main cultural legacy is its ability to provoke a necessary discourse on slavery and racism in the present” in “a nation that remains bitterly divided by racism, race consciousness, and the unresolved memory of slavery.” It isn’t clear that the nation was “bitterly divided” about racism or “the unresolved memory of slavery” (whatever that means) in 2009 or that it is now, except in the imagination of people like Vollaro. Racism is generally condemned. Division is sown by those who appropriate our language and attempt to redefine as racist any policies they dislike. [↩]