The story never loses its fascination. Two brothers, “inseparable as twins,” their father said, innocently set out to solve one of the greatest technical problems of human history. They had no academic or professional training in physics or engineering. They were bicycle mechanics. Yet in only a few years of experiments, conducted entirely at their own expense under what can only be described as primitive conditions, the Wright brothers accomplished their goal, unlocking secrets that eluded the so-called experts. They learned how to fly.

Wilbur Wright was thirty-two and Orville Wright was twenty-eight in 1899 when they decided to experiment with sustained heavier-than-air flight. Neither had more than a high school education, a fact that should command our attention. High school now qualifies young Americans for little more than menial work and many employers in creative and analytical fields expect applicants to hold post graduate degrees. It would be easy to attribute the Wrights’ achievement to genius, a natural characteristic beyond the reach of education, but in their case this would be quite wrong. Both Wrights had an unusual aptitude for solving mechanical problems, but in each of them it was combined with independence of mind and spirit, patience, humility, confidence, determination, the ability to focus, and no small amount of courage.

Hardly any of these characteristics were innate. They were learned in youth in a family in which they were cultivated and cherished by their father, a bishop of the United Brethren Church, and their mother, who died in 1889, and encouraged by a large and supportive family. Their house was filled with books and their parents promoted intellectual inquiry. They grew into earnest, hard-working young men who absorbed all that their schools had to offer, at a time when good high schools offered a more thorough education than most modern colleges. Their genius, properly understood, was carefully cultivated.

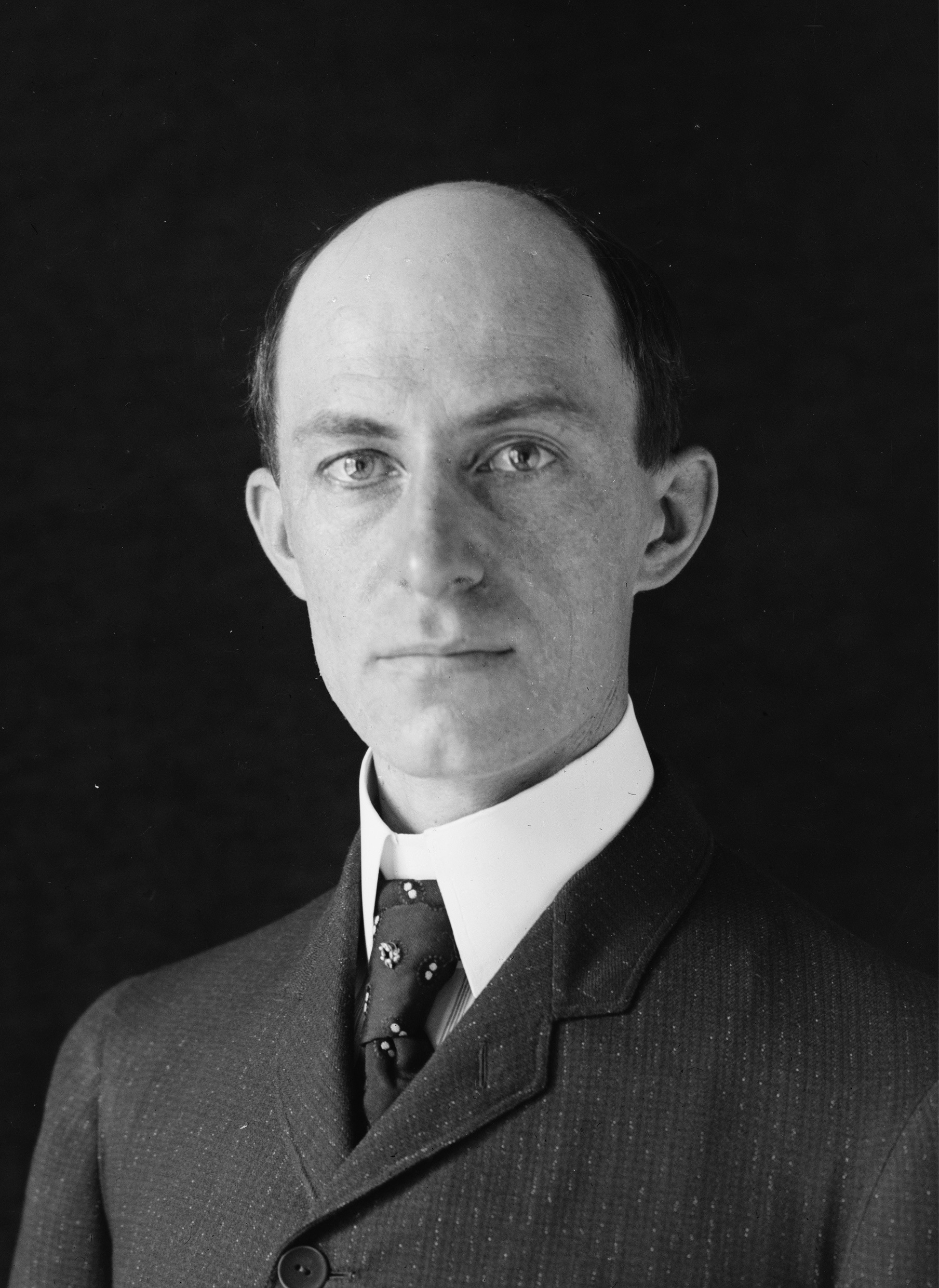

Wilbur Wright, about 1905 (Papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright, Library of Congress)

They were Christian gentlemen of a very American sort — tradesmen who saw nothing undignified about working with their hands and who quietly regarded themselves as the equal of college educated men, of wealthy men, and ultimately of aristocrats and kings. Their minds were too restless to be satisfied with the mundane work of building and repairing bicycles, but they never spurned or disparaged it. They had no vices. They did not drink, smoke, or swear. They did not work on the Sabbath. They were unfailingly honest, polite, and dignified, and typically wore suits and ties in company, even when flying. Wilbur was a bit taciturn, even socially withdrawn. He lost several of his front teeth in a hockey accident when he was a teenager and even after he was fitted with dentures it took him several years to be comfortable speaking in public. He had no interest in fashion. In group photographs he is easy to pick out — among grinning men with turn-of-the-century handlebar mustaches he’s the clean shaven man with dark, deep-set eyes, his mouth clamped, staring forward intently. Orville was charming, fun loving, and something of a dandy. His letters are full of warmth and humor. Wilbur devoted his correspondence to business and technical matters.

They were devoted to their family and both leaned heavily on their sister, Katharine, who was younger than Orville and a graduate of Oberlin — the only college graduate in the family. Katharine taught high school, managed the household, and supported her brothers in their work, ultimately handling their correspondence and a large part of their business affairs.

They were also happily provincial — comfortable in Dayton, where they lived with their widowed father and sister and close to an extended family that included two older brothers. They had no interest in the pleasures of big city life. They enjoyed seeing London and Paris but were not seduced by their charms nor moved by the attention of famous and wealthy people. Their own fame, when it came, did not change them much. They spent part of the money they earned building a big handsome house in Dayton — Wilbur did not live to see it finished — into which Orville moved with his father and Katharine. Orville sold the airplane business in 1915 and lived there for the rest of his long life.

Orville Wright, about 1905 (Papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright, Library of Congress)

The Wright brothers have come down to us as an inseparable pair who solved the problem of flight together. Wilbur always insisted that about the same credit was due to each of them, but a cursory examination of the record of their work demonstrates that Wilbur was the senior partner in more than years. A writer once proposed to describe them in an article as “Wilbur Wright & Bro.,” but Wilbur insisted on “Messrs. Wilbur and Orville Wright.” Nonetheless, it was Wilbur who first took up the problem, and it was he who solved many of the practical engineering puzzles involved. Wilbur died in 1912, at the height of his fame.1

Orville lived for thirty-six more years but never invented anything important on his own. He had great talent for mechanical work and solving practical problems and was utterly fearless, but his most important contribution to the partnership may have been to keep Wilbur going. Wilbur was given to brooding over very difficult problems and his brooding sometimes gave way to despondency. Orville was reflective, optimistic, and unfailingly supportive. He helped Wilbur overcome his doubts. They argued about technical matters and debated the best ways to solve difficult problems but invariably presented a united front to the world. They were true partners. To suggest otherwise is an injustice to their memory and their values — the virtue of hard work, the importance of family, sharing in success, and personal loyalty.2

Profits in the Air

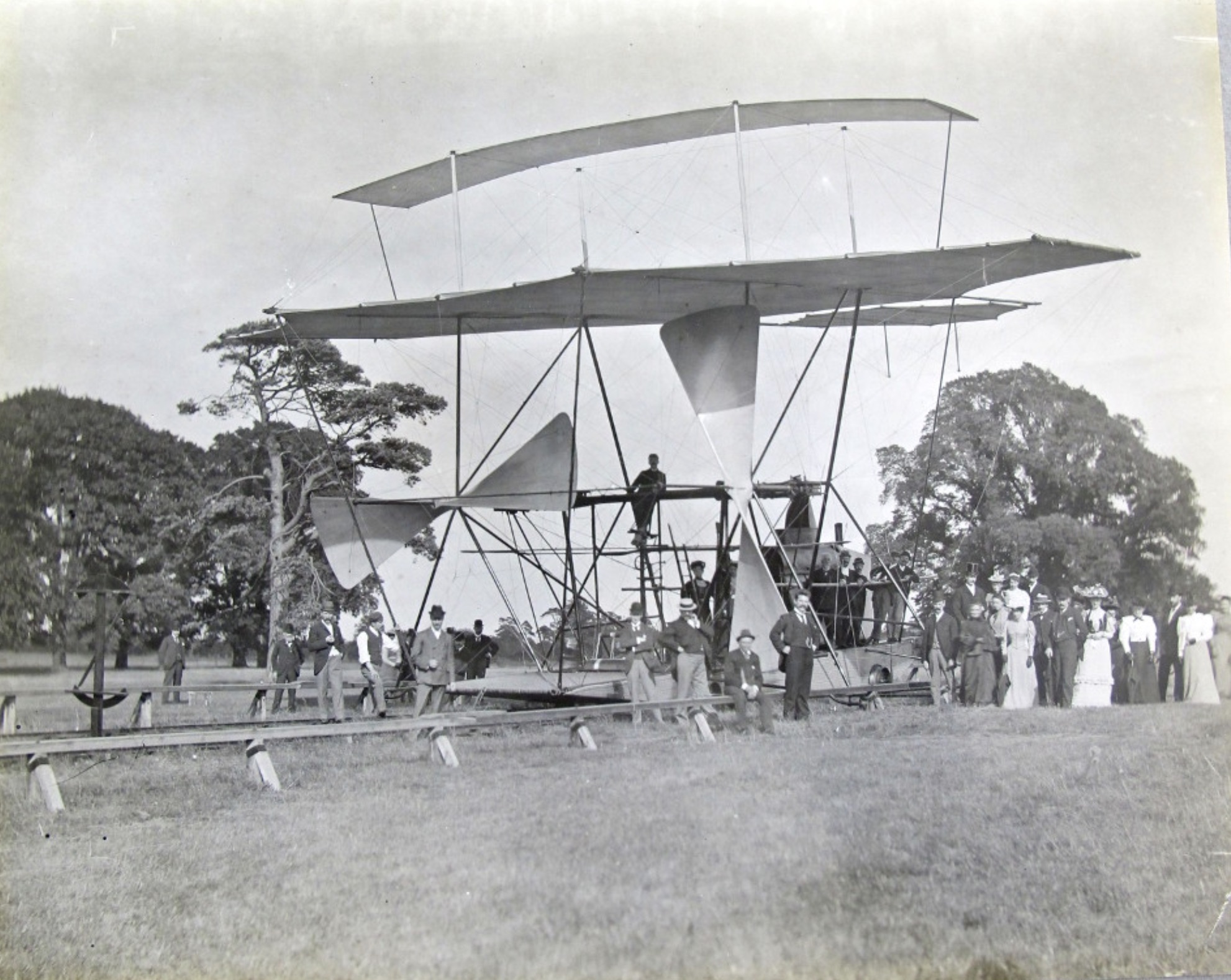

The basic principle of lift that makes heavier-than-air flight possible was already understood — though not particularly well — when the Wrights began their work, but no experimenter had managed to use it to achieve sustained powered flight. Some tried to fly by brute force, attaching powerful engines to heavy flying machines and shoving them into the air. In 1894 Hiram Maxim, inventor of a prototype machine gun, attached two 150 horsepower steam engines to a multi-winged contraption weighing over four tons. It shuddered under its own weight and rose from the ground, only to collapse in a heap of wings and wire after flying a few feet. Maxim declared theoretical success and walked away from flying for good. Others made even more ludicrous attempts to fly, their lunatic stunts involving catapults and suicidal leaps from cliffs, some recorded by primitive movie cameras. The one thing these flying machines had in common was a comic inability to fly. A few made short hops before crashing.

Hiram Maxim’s 1894 “flying machine,” which weighed four tons, never flew. It reflected the common nineteenth-century obsession with the capacity of mechanical power — the more the better — to solve engineering problems. (Vickers Archive, Cambridge University Library)

Those who managed to take off confronted the real flying problem — controlling their machine once it was in the air. A few flight enthusiasts appreciated this and pursued the principles of control by practicing with gliders. This work could have deadly consequences. Otto Lilienthal, a German experimenter, died piloting a glider in 1896. Three years later Englishman Percy Pilcher died when his glider broke up in flight. Their deaths cooled interest in flight at precisely the moment the Wrights were beginning their work.

After the deaths of Lilienthal and Pilcher, skeptics began to suggest that heavier-than-air flight was unattainable, a mirage like perpetual motion. Even those who thought that it was possible could not imagine much practical value in flying. The great inventions of the nineteenth century had immediate, practical, commercial applications. Steam engines had been brought to a high degree of perfection as a source of power for locomotives and industrial plants; the light bulb promised a cheaper and safer means of illumination than kerosene or gaslight; the internal combustion engine promised to provide an alternative, and ultimately a replacement, for the horse and the mule.

Many serious inventors thought that heavier-than-air flight, though theoretically possible, would never be much more than a circus stunt. Edison tinkered with propellers in his laboratory and singed his hair while working on a lightweight internal combustion engine fueled by long tapes of nitrate soaked paper, then gave up. No one except science fiction writers imagined flying machines that could carry hundreds of people or large cargoes over vast distances. The future of air travel, such as it was, seemed to lie with lighter-than-air craft like the semi-rigid and rigid airships being developed in Europe — a ponderous and slow but seemingly reliable way to fly. There seemed to be no profit in heavier-than-air flying machines.

If there seemed to be little money in the thing, at least the Wrights did not have to contend with too many competitors. Wilbur explained this to his father in a letter written just as the brothers were beginning their practical experiments: “It is my belief that flight is possible and while I am taking up the investigation for pleasure rather than profit, I think there is a slight possibility of achieving fame and fortune from it. It is almost the only great problem which has not been pursued by a multitude of investigators, and therefore carried to a point where further progress is very difficult.”3

Marginalized by circumstances, the flying problem attracted an increasing number of cranks and charlatans, dreamers, oddballs, and self-promoters given to making unverifiable claims of improbable flights. The Wrights were pillars of honesty in their company, like Sunday-school teachers at a convention for confidence men. Their only serious competitor, they concluded, was Samuel Pierpont Langley, the scholarly, well-financed head of the Smithsonian Institution. Langley had flown large unmanned models powered by miniature steam engines in still air over the Potomac River. They ended their flights by crashing into the river, as Langley expected. The experiments proved that powered heavier-than-air-flight could be sustained, but Langley had not devised reliable methods to control or land a flying machine — obvious prerequisites for manned heavier-than-air flight.

Wind and Sand

Langley had only proved the obvious — that an airfoil generating sufficient lift and stabilized with a vertical tail can fly through still air when driven by a propeller powered by an engine generating sufficient force. The Wrights recognized that the central problem of operating a flying machine, like riding a bicycle, was maintaining control while in motion, a delicate business in which the force generated by an engine plays a secondary role. They concluded at the start of their work that mastering control in gliding flights and adapting their gliders to the lessons they learned through practice was the only way to unlock the secrets of flight.

Practicing with gliders was a dangerous business that had cost Lilienthal and Pilcher their lives. A prudent man determined to minimize risk, Wilbur settled on Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, to carry out their flying experiments. He chose Kitty Hawk — a scrawny, threadbare village on the remote Outer Banks — because it offered steady winds to sustain their gliding flights and sand to cushion landings, conditions not found near their home. Much of the landscape — sandscape is perhaps a more descriptive word — was mostly barren of trees and other hazards. It was also conveniently remote from prying eyes of curiosity seekers and would-be competitors.

The Wrights first ventured to Kitty Hawk in the fall of 1900 and made camp near the village. Orville doubted that many people would “think of the place as a scene of beauty.” The Outer Banks, he wrote, “looked very much like the Sahara Desert, as I imagine that to be. There was little excepting sand and sand dunes and sky,” though he admired the sunsets which he called “the prettiest I have ever seen.” The place has changed considerably in the last 120 years, but the feature that attracted the brothers to Kitty Hawk — the steady wind they needed keep their gliders aloft — still blows across the narrow spit of sand.4

They began their experiments with a small biplane glider made from materials carried from Dayton by rail and fishing schooner to Kitty Hawk. It consisted of two stacked lightweight wings, seventeen by five feet each, framed in white pine (purchased en route in Norfolk) with ash ribs to provide the curve for the wings, which were covered in muslin and connected by rigid pine struts reinforced with diagonal wires. The two wings provided sufficient lift to carry a man in a strong, steady breeze. A single wing glider of sufficient size to provide the same lift would have to have been more heavily built and more than twice as large.

A biplane glider with wings connected by struts and wires was not original to the Wrights. Octave Chanute, a successful Chicago civil engineer with whom Wilbur corresponded, had sponsored trials with a similar biplane glider in the Indiana Dunes in 1896. But the Wright glider differed from it in essential ways. The Wrights included a system of wires for maintaining lateral equilibrium by curving the wing tips on either side. Chanute, who visited the Wright’s camp in 1901, called this technique “wing-warping,” though he never seems to have grasped its purpose. Wilbur had conceived this method of maintaining equilibrium in imitation of the way birds adjust the tips of their wings in flight, but he also imagined it as a way to make banking turns, much like a bicyclist leans into turns. Other investigators, Chanute included, were convinced that flying machines had to be self-leveling and steered with a rudder, like a ship in the air, executing broad arcing turns in level flight.5

The brothers spent much of their time flying their glider as a kite, manipulating the wing-warping control from the ground. Wilbur made a few gliding flights toward the end of their experiments. The experience convinced them that they could design a practical flying machine, capable of sustained powered flight that could also execute sharp turns and fly back to its starting point.

From the start they looked beyond the immediate challenge of getting into the air and landing safely to the engineering problem of building a useful flying machine. They weren’t dreamers or theorists. They were practical engineers working in a field that barely existed and that they were in process of inventing. They were isolated from academics and engineers who approached flight with theories, techniques, and assumptions based on naval architecture, railroads, and windmills. Some of those ideas were useful, but many of them were flawed or inapplicable to the flying problem. Isolation from them was, on balance, a benefit.

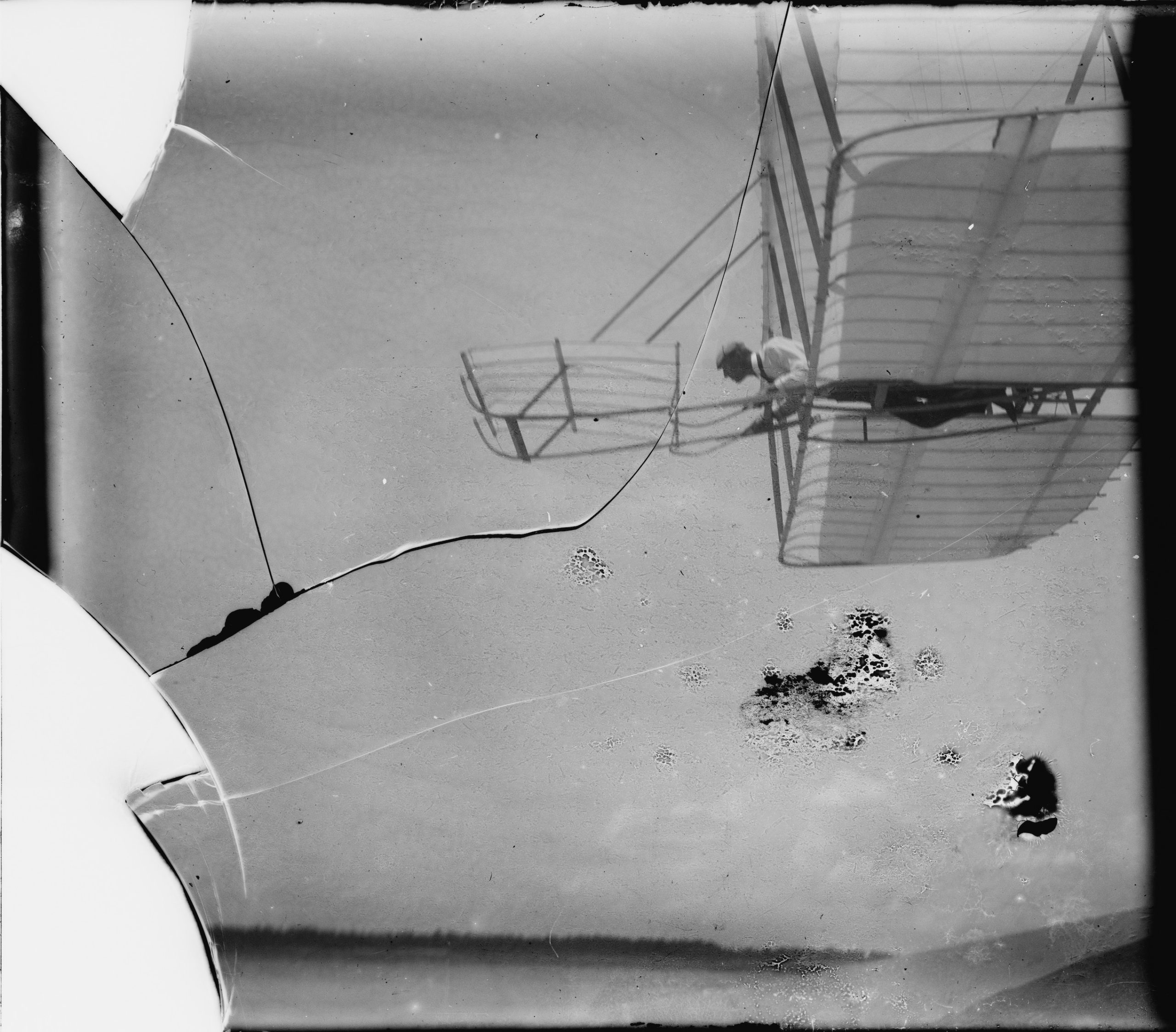

The Wrights attracted the attention of locals, including young Tom Tate, posing here in front of the 1900 glider with a drum fish caught in the surf. Forty pounds lighter than either of the Wrights, Tom proved to be the right weight to ride the glider as a kite and with his father’s permission he was the passenger on an experimental flight. The brothers carefully photographed their experiments and the people they met with a large format camera exposing glass plate negatives. Many of the plates were damaged by a flood in Dayton in 1913, which accounts for the losses to many of the images. (Papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright, Library of Congress)

“Misery, Misery!”

It took two more years of experiment, frustration, calculation, design, testing, and practice to build and operate the kind of glider they imagined. The brothers spent the winter making calculations and plans and returned to the Outer Banks in the summer of 1901 to carry out the serious, systematic glider experiments that would lead to the first powered flight.

They made camp four miles south of Kitty Hawk, close to Big Kill Devil Hill, a dune some one hundred feet high — ideal for launching their glider. They returned there in 1902 and 1903, when they achieved the first powered flight on the level sand at the base of the hill. The site is now preserved as Wright Brothers National Memorial, a popular cloudy-day destination for vacationers. Each summer thousands of people climb Big Kill Devil Hill and admire the panoramic view of the ocean shore, now lined with beach cottages and hotels. The National Park Service has nurtured shrubs and grasses in an effort to hold the shifting sands in place and preserve in a way the place where the brothers carried out their experiments. The work has changed the sandy dunes into a swath of green.6

The Wrights had little patience for guesswork and no intention of risking their lives unnecessarily. They wanted not just to fly, but to understand the principles that made flight possible. Reputed experts had developed elaborate aerodynamic theories, buttressed by complex tables of lift and drag. The Wrights found that the theories were mostly wrong and the tables were nearly all flawed, but not before passing through a crisis of confidence that nearly caused them to give up their work.

To judge from Orville’s account, mosquitoes did most of the real flying at Kitty Hawk that summer. “They chewed us clear through our underwear and socks,” Orville wrote. “We attempted to escape by going to bed . . . wrapped up in our blankets with only our noses protruding.” But the night was hot and “the perspiration would roll off us in torrents. We would partly uncover and the mosquitoes would swoop down upon us in vast multitudes. We would make a few desperate and vain slaps, and again retire behind our blankets. Misery! Misery!”

The next day the campers constructed net covered frames to surround their cots, but the enemy soon “gained the outer works.” The young aeronauts “were put to complete rout” and spent the evening “rushing all about the sand for several hundred feet around trying to find some place of safety.” The next night they built smoky fires to drive the mosquitoes away, which proved moderately successful, though a guest in camp couldn’t stand sleeping in the smoke and spent a miserable night retreating “from mosquito to smoke and from smoke to mosquito.”7

The pilot — Wilbur in this photograph of the 1901 glider in flight — operated the wing-warping mechanism by pressing on a wood bar with his left or right foot, which tightened the wires on the corresponding side and curved the wing tips on that side toward one another, causing the opposite side to rise. In later years the Wrights replaced the bar with a hip cradle allowing the pilot to operate the mechanism by shifting his weight to right or left. The wing-warping mechanism on the 1901 glider did not work as well as the brothers expected. Without a rudder at the back, the glider began to turn but then slipped on its vertical axis and resumed level flight. To control this phenomenon, called yaw, the Wrights added a rudder to their 1902 glider. The 1901 glider included a horizontal elevator in the front which Wilbur is manipulating in this photograph to control pitch. (Papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright, Library of Congress)

The mosquitoes were only part of their misery. They encountered technical problems so perplexing that they nearly abandoned the idea of flying altogether. The Wrights had based their wings on lift tables devised by Lilienthal, which serious men of science believed to be the best available, but none of the Wright’s gliding flights went as the tables suggested they would. They left Kitty Hawk in late August with their confidence badly shaken. Wilbur wrote that they “considered our experiments a failure” and doubted that they would ever resume their work. He predicted that “men would sometime fly, but that it would not be within our lifetime.”8

Wilbur’s despondency passed in a few weeks, and out of the confusion and frustration of that summer’s experiments came an epiphany. The so-called experts were wrong. If he and Orville were going to understand aerodynamics he realized they would have to do their own experiments and devise their own tables of lift and drag. He realized that they had little to learn from others. Back in Dayton the brothers developed their own theories and tested them in the first practical wind tunnel, a machine they constructed in the room above their shop. They made the balances used in the tunnel out of old hacksaw blades and bits of scrap metal. They devised their own tables and used them to design a new glider based on scientific data they alone possessed.

“the age of the flying machine . . . come at last”

They returned to Kitty Hawk in 1902 with a glider truly their own. It was larger than their 1901 glider and the wings, with a design based on their wind tunnel experiments, provided greater lift and control. To improve stability in the vertical axis they included a tail with a fixed rudder or vane. Practice demonstrated that the fixed vane interfered with turns, so the brothers put it on a hinge and added a mechanism to turn the vane. The 1902 glider then performed more or less as their experiments predicted. It was the first flying machine with true aeodynamic control, with mechanisms to manage pitch, yaw, and roll in any combination. The Wrights flew the 1902 glider more than 1,000 times that fall.

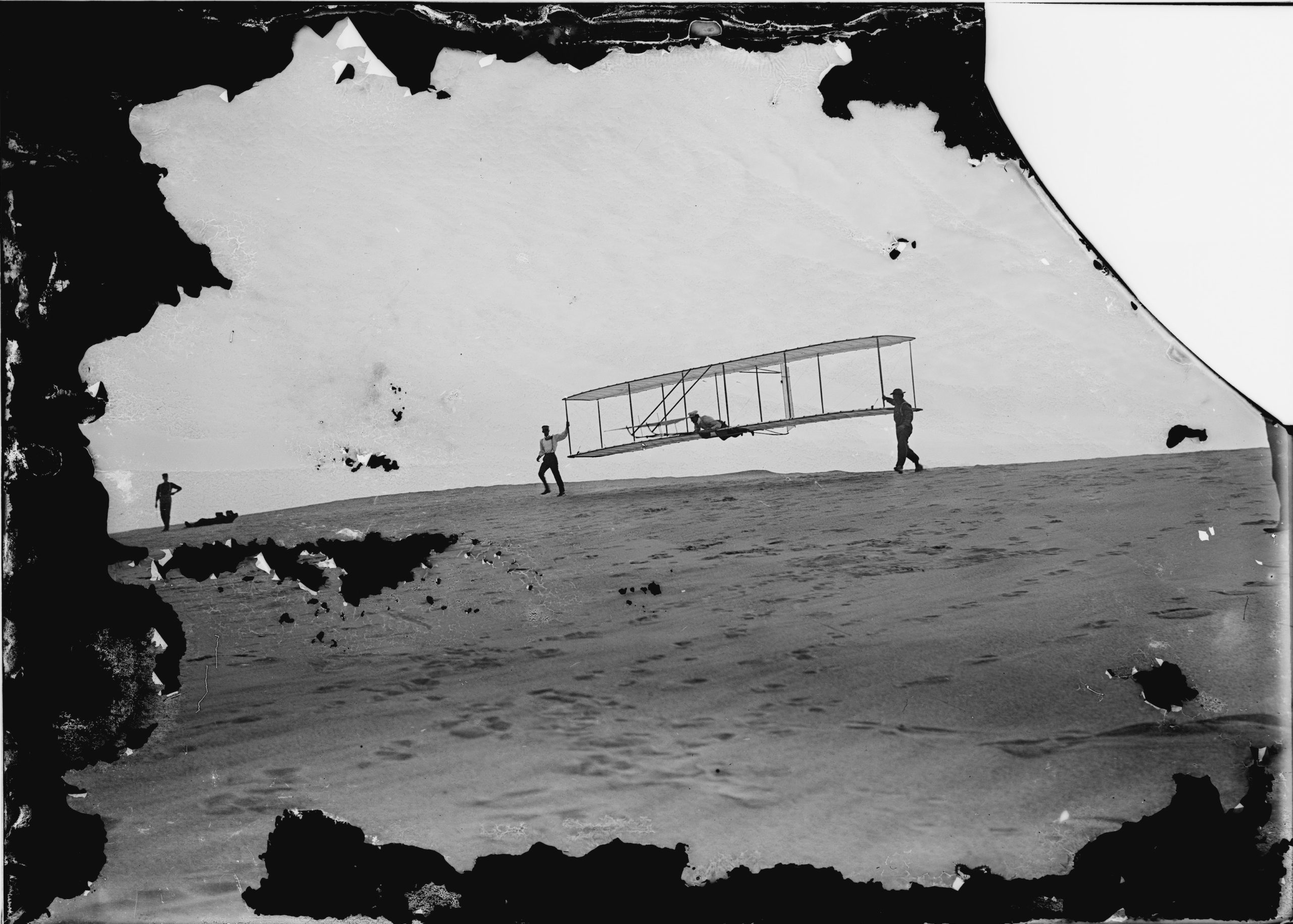

The Wights relied on the help of men from the local Life Saving Station to launch the 1902 glider. (Papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright, Library of Congress)

The brothers continued to refine their tables in 1903 and took up the issue of propeller design, confidently rejecting all previous work on this subject as worthless. They designed their own propellers, and when they could not find a motor that met their exacting specifications, they had a skilled mechanic in their Dayton bicycle shop build one to their specifications. It generated just twelve horsepower — all they calculated they would need to generate lift.

When the Wrights arrived in Kitty Hawk in the fall of 1903 to test their flyer, they had no doubt they would succeed. They understood the technical issues involved in flying better than anyone alive, and they knew it. They spent two months practicing with and adapting the 1902 glider while putting the finishing touches on their new machine, with the little engine connected to the propellers with bicycle chains. The climactic moment, on December 17, 1903, when the new machine took off under its own power, was almost devoid of drama. Chance played no part in it at all. The Wrights had overcome, through deliberate, thoughtful, and well-planned efforts, every obstacle in their way.

Hoping to photograph their first powered flight, Orville set their camera on its tripod and focused it on the point where he expected the flying machine to take off. Wilbur handed the shutter release to John Daniels, a local man who had come down from the Life Saving Station, and told him to squeeze the shutter release if anything interesting happened. The bench in the foreground supported the end of the wing while the brothers readied the flyer and started the motor. To the left of the bench you can see the undisturbed sand that was below the wing before the flight. It’s surrounded by the footprints the Wrights made while checking the flyer and getting ready for the flight. The flyer had no wheels — it sat on a low cart that rolled down a single wooden rail once the propellers began turning. Wilbur trotted alongside to make sure the wings remained level. With Orville at the controls, the flyer rose from the rail. Two or three seconds later Daniels squeezed the shutter release, taking one of the most historic, perfectly timed photographs ever made. (Papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright, Library of Congress)

We recognize that the moment the first Wright flyer took off as a watershed in modern history. Contemporaries did not understand its importance, at least at first. The brothers sent a brief telegram to their father announcing “success four flights” and asked him to inform the press immediately. Their older brother Lorin took the news to the Dayton Journal that afternoon. The Associated Press representative at the paper was unimpressed. A flight of fifty-seven seconds, he asked? “If it had been fifty-seven minutes,” he told Lorin, “that might have been a news item.” He declined to distribute the story.9

A reporter in Norfolk, Virginia, who learned the contents of the Wright telegraph was impressed. The next day’s headline in the Norfolk Virginian-Pilot announced: “Flying Machine Soars 3 Miles in Teeth of High Winds over Sand Hills and Waves at Kitty Hawk on Carolina Coast.” The story reported that “The problem of aerial navigation without the use of a balloon has been solved at last.” Two Ohio men had “proved that they could soar through the air in a flying machine of their own construction, with the power to steer it and speed it at will.”

Alas for the reputation of journalists, little in the story was true. “Like a monster bird,” the story went on, “the invention hovered above the breakers and circled over the rolling sand hills at the command of its navigator and, after soaring for three miles, it gracefully descended to earth again and rested lightly upon the spot selected by the man in the car as a suitable landing place.” The story was republished in the New York American and the Cincinnati Enquirer. The Associated Press then distributed an abbreviated version of the Virginian-Pilot story, which showed up in newspapers across the country. In Dayton a headline announced “Dayton Boys Emulate Great Santos-Dumont,” suggesting the Wrights had imitated Alberto Santos-Dumont, who had piloted a cigar-shaped dirigible around the Eiffel Tower in 1901. The distinction between a lighter-than-air contraption and the Wright’s flying machine was opaque to many people, though the story explained that the Wright flyer “has no gas bag or balloon of any kind.”10

The first flight had actually covered 120 feet. The longest of four flights that day covered 852 feet in fifty-nine seconds. The Wrights were so disturbed by the absurd Virginian-Pilot story that they issued a statement to the Associated Press describing their flights. For such an extraordinary accomplishment the report was remarkably simple and matter-of-fact:

On the morning of December 17th, between the hours of 10:30 o’clock and noon, four flights were made, two by Orville Wright and two by Wilbur Wright. . . .Each time the machine started from the level ground by its own power alone with no assistance from gravity, or any other sources whatever. After a run of about 40 feet along a mono-rail track, which held the machine eight inches from the ground, it rose from the track and under the direction of the operator climbed upward on an inclined course till a height of eight or ten feet from the ground was reached, after which the course was kept as near horizontal as the wind gusts and the limited skill of the operator would permit. . . . the first flight was short. The succeeding flights rapidly increased in length and at the fourth trial a flight of 59 seconds was made, in which time the machine flew a little more than a half mile through the air, and a distance of 852 feet over the ground. . . . As winter was already well set in, we should have postponed our trials to a more favorable season, but for the fact that we were determined, before returning home, to know whether the machine possessed sufficient power to fly, sufficient strength to withstand the shock of landings, and sufficient capacity of control to make flight safe in boisterous winds, as well as in calm air. When these points had been definitely established, we at once packed our goods and returned home, knowing that the age of the flying machine had come at last.11

Riding the Air

The Wright brothers had yet to build a practical flying machine — one capable of taking off without the aid of steady wind, remaining aloft for extended periods, turning to fly a complete circuit, and landing without damage to the machine or injury to the operator. Doing so required adapting their flyer to perform in still air and practicing with it until they learned to fly. At the beginning of 1904 they turned the operation of the bicycle shop over to an assistant and began work on a new flyer, which varied only slightly from the 1903 model. The main difference was a motor generating sixteen horsepower, which the brothers calculated they would need to fly in still air.

They chose Huffman Prairie — an unremarkable level tract eight miles east of Dayton — as their new practice ground. Huffman Prairie had the benefit of being close to home, easily accessible by an electric trolley line that passed the property. People would see them fly, of course, and inevitably some of them would stop and ask questions.

To satisfy local curiosity and show their family and neighbors what they had accomplished, the brothers invited some forty people to witness the first trial of the new machine. The group included a dozen reporters, but the Wrights excluded photographers. They were anxious to prevent would-be competitors from having pictures until they secured patents on their invention. On the afternoon of May 23, with the little crowd on hand, the Wrights started the engine. The air was still and the engine misfiring. The flyer started down the hundred-foot rail but never reached sufficient speed and rolled off the end of the rail without taking off. It then rained for two days. The brothers tried again on May 26 for a smaller group of spectators. This time Orville managed to fly for twenty-five feet.12

Huffman Prairie — now part of Wright-Patterson Air Force Base — was largely free of trees and other hazards. It was also in sight of several farmhouses, one of which is visible in the background of this 1904 photograph. The device mounted to the strut behind Wilbur (at right) is an anemometer that recorded the airspeed. (Papers of Orville and Wilbur Wright, Library of Congress)

The reporters went away with nothing much to report. “I sort of felt sorry for them,” the managing editor of the Dayton Journal said. “They seemed like well-meaning decent young men. Yet there they were, neglecting their business to waste their time day after day on that ridiculous flying machine.” Perhaps the Wrights didn’t intend to put on a real flying exhibition and had invited the press to watch an unimpressive display to discourage interest in their work that summer. “The best way to keep a secret,” one of the brothers told a visitor, “is to avoid letting anybody know you have a secret to keep.”13

For much of the summer they did no better than short hops of one to two hundred feet. They beat the Kitty Hawk record of 852 feet on August 13, but on August 24 Orville crashed the flyer on takeoff when the breeze died. In still air the flyer didn’t move down the rail fast enough. To solve the problem, the brothers rigged up a derrick with a heavy weight attached to a mechanism that pulled the flyer down the launching rail at sufficient speed to generate lift. Longer flight became routine. By September 15 they were able to fly for half a mile and execute a ninety-degree turn. Then on September 20 Orville flew completely around Huffman Prairie, a distance of 4,080 feet.

Amos Root, the editor of a folksy periodical called Gleanings in Bee Culture, witnessed the flight. He had traveled by automobile from his home in Medina, Ohio, to meet the brothers and happened to be there for the landmark flight. Root was anxious to publish an account of what he saw but waited patiently until the Wrights approved. Thus the first independent eyewitness description of a successful airplane flight was published, not in a scientific periodical or a major newspaper, but in a magazine for bee keepers.

Root called it a story that “out-rivals the Arabian Nights.” He had seen “the first successful trip of an airship, without a balloon to sustain it, that the world has ever made, that is, to turn the corners and come back to the starting-point.” He grasped for a way to describe it, suggesting readers “imagine a locomotive that has left its track, and is climbing up in the air right toward you ― a locomotive without any wheels, we will say, but with white wings instead . . . Well, now, imagine this white locomotive, with wings that spread 20 feet each way, coming right toward you with a tremendous flap of its propellers. It was, Root concluded, “one of the grandest and most inspiring sights I have ever seen.” Root thought that everyone would soon take to the air, doing away with the need for roads and bridges.14

By the end of 1904 the Wrights were circling Huffman Prairie as many as four or five times and remaining aloft for more than five minutes. Most flights were shorter and the flyer was not always easy to control — particularly pitch, which did not respond to the elevator as they wished. Hard landings and minor accidents remained common.

In the May 1905 they built a new flyer, aiming to correct the problems encountered in 1904. They used the same engine but included separate controls for wing-warping and turning the rudder, which had been linked in earlier flyers. The brothers enlarged the rudder and the elevator but the flyer continued to undulate as it flew, pitching and rising. In August the Wrights modified the design again, dramatically enlarging the elevator and moving it some five feet forward. That solved the problem. Flights grew longer and accidents fewer. On October 5, in plain view of dozens of witnesses, Wilbur flew until his fuel ran out, covering more than twenty-four miles in thirty-nine minutes before landing safely. They had built the first reliable aircraft capable of sustained flight and learned how to fly it. In his diary entry for the day Wilbur made note of the distance and time and added “Experiments discontinued for the present.” They had learned the secret of flight and had nothing more to prove to themselves.15

The Wright brothers were technically gifted and creative men. This accounts for their inventiveness. But they were also courageous and determined men, at once systematic and daring, humble and self-assured, confident in their ability to succeed at something many people regarded as impossible. Their character, as much as their inventiveness, was the source of their achievement. The secret they had discovered was not wing-warping or the particular design of wings, elevators, and rudders. Others in time would devise more effective methods of controlling aircraft. The secret of flight, Wilbur told Carl Dienstbach, the American correspondent of a German aeronautics journal, “is the man; not the machine.” Wilbur added that “if from another planet a perfect flying machine were dropped to the Earth, it would not help men to fly. They could not use it and would then begin trying to improve on the design and end by ruining the whole thing.” The Wright brothers “great scientific discovery,” Dienstbach concluded, was not their airplane. It was learning “how to ride it on the air.” Their invention has been eclipsed, but their achievement remains a symbol of technological virtuosity and a testament to virtue.16

Five years of diligent, systematic work culminated in the historic flights over Huffman Prairie in the fall of 1905. Wilbur took this photograph on September 29, when Orville circled the prairie fourteen times. (Papers of Orville and Wilbur Wright, Library of Congress)

Learn More: The Wrights are the subject of many books. Among the best are Tom Crouch, The Bishop’s Boys: A Life of Wilbur and Orville Wright (New York: W.W. Norton, 1989), James Tobin, The Wright Brothers and the Great Race for Flight (New York: Free Press, 2003), and David McCullough, The Wright Brothers (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015). You can explore the Papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright online at the Library of Congress.

You can visit Wright Brothers National Memorial in Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina, the site of the gliding experiments of 1901-1903 and the first powered flight, as well as Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park, in and around Dayton, Ohio, which includes one of the Wright bicycle shops, Hawthorne Hill, the home of Orville Wright from 1914 to 1948, and Huffman Prairie, where the Wrights perfected their flying machine. You can see the original 1903 flyer on permanent display at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. The 1905 flyer and the Korona V camera used by the Wrights are on display in the Carillon Historical Park in Dayton. Henry Ford bought the Wright home and the rented building that housed the Wright Cycle Company from 1897 to 1908, originally at 1127 West Third Street in Dayton, and moved them to Greenfield Village, his museum complex in Dearborn, Michigan, now called The Henry Ford. The Ford museum also displays a wide range of tools and other objects owned by the Wrights and a replica of the 1903 flyer.

The National Air and Space Museum has developed a collection of very fine resources for teachers and students (and the rest of us, too) on the Wright brothers. In this brief video, historian and curator Tom Crouch explains wing-warping using a model of the Wright’s 1900 glider. In another, he points out the details — some of which are easy to miss — in the famous photograph of the first flight.

For more articles, reflections, and commentary on our shared past, subscribe now to The American Crisis.

Notes

- Wilbur Wright to Octave Chanute, December 3, 1900, McFarland, ed., Papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright (see note 2), 1: 49. [↩]

- The most important source for studying the Wrights is the Papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright that Orville left to the Library of Congress. Most of the important correspondence can be found in Marvin McFarland, ed., The Papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright (2 vols., New York: McGraw-Hill, 1953), which includes important letters and diary entries by their father, Bishop Milton Wright, and others. Bishop Wright’s statement that the brothers were “inseparable as twins,” quoted in the first paragraph, is found in Milton Wright to Carl Dienstbach, December 22, 1903, McFarland, ed., Papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright, 299-400. Orville also left the brothers’ large collection of glass plate negatives to the Library of Congress. Arthur Renstrom, Wilbur and Orville Wright — Pictorial Materials: A Documentary Guide (Washington: Library of Congress, 1982) is a thorough guide to this collection. The Wrights are the subject of several biographies. Fred Kelly, The Wright Brothers (New York: Harcourt, Brace, and Company, 1943), was authorized by Orville, who assisted Kelly, a journalist and friend, in the work. Orville even signed copies of the book. The most insightful modern biography — Tom Crouch, The Bishop’s Boys: A Life of Wilbur and Orville Wright (New York: W.W. Norton, 1989) — combines an appreciation of the cultural circumstances that shaped the Wrights with a thorough understanding of their technical achievement, which the author, a longtime curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Air and Space, conveys in language a layman can grasp. James Tobin, The Wright Brothers and the Great Race for Flight (New York: Free Press, 2003) is particularly useful for locating the Wrights among those trying to achieve heavier-than-air flight. He does a particularly good job with Samuel Pierpont Langley. David McCullough, The Wright Brothers (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015) is less satisfying on technical matters, but is graceful and reflects the command of the period he has displayed in books on the Brooklyn Bridge, the Panama Canal, and Theodore Roosevelt. Katharine Wright emerges as an important character in McCullough’s version of the story. Despite the fascinating nature of their achievement and the richness of the documentary record they maintained, the Wright brothers are a difficult subject for biographers. They were so methodical and their relationship so devoid of conflict that their story lacks drama. Their creative virtuosity is enough to carry the story through 1905, when they were ready to exhibit and sell their flying machines, but thereafter their lives were tangled in marketing efforts and patent disputes. Their triumphant exhibitions in Europe and Wilbur’s memorable flights at the 1909 Hudson-Fulton Celebration are the climactic scenes in the brothers’ partnership. Wilbur’s sudden death from typhoid fever in 1912 truncates the story in a tragic, unsatisfying way. Orville lived on for decades in the shadow of their great achievement without adding to it. A more recent book, William Hazelgrove, Wright Brothers, Wrong Story: How Wilbur Wright Solved the Problem of Manned Flight (Amherst, N.J.: Prometheus Books, 2018) contends that Orville was really a skilled mechanic and assistant to Wilbur who manipulated Fred Kelly’s authorized biography to exaggerate his own role in the development of powered flight. Crouch, Tobin, McCullough and others recognized Wilbur as the senior partner in the work and Crouch sketched the difficulties Kelly had in dealing with the aging Orville’s demanding nature, so there is nothing deeply original in Hazelgrove’s argument other than his animus toward Orville. Hazelgrove exaggerates the reliance of modern biographers and scholars on Kelly’s book. Crouch and McCullough based their account of the Wright’s technical work on original sources, most importantly the Wright’s own correspondence and papers at the Library of Congress. Crouch, moreover, understood the engineering issues far better than Hazelgrove and was in a far better position to assess Orville’s contributions to the partnership. Hazelgrove simply ignores the abundant evidence of Orville’s contributions to the work, including documents written by Wilbur. [↩]

- Wilbur Wright to Milton Wright, September 3, 1900, quoted in McFarland, ed., Papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright, 1:14. [↩]

- Orville Wright to James Calvert Smith, February 11, 1933, McFarland, ed., Papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright, 2: 1161; on the sunsets, Orville Wright to Katharine Wright, October 14, 1900, McFarland, ed., Papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright, 1: 28-34. [↩]

- Chanute is an intriguing figure in the development of powered flight, which he embraced as a cause after a successful career designing railway bridges. He was sixty-four in 1896 — too old to make gliding flights himself — and lacked the craft skills to build a flying machine, but he sponsored experiments by others and offered technical advice. His chief role in the development of powered heavier-than-air flight was encouraging experimenters to communicate with one another and share their ideas. Chanute erred in supporting and trusting untrustworthy men. The Wrights read his 1894 book, Progress in Flying Machines, and Wilbur exchanged hundreds of letters with Chanute, who became an important sounding board for Wilbur. The two ultimately fell out. Chanute believed that he played a major role in the Wright’s success, which Wilbur insisted was based on innovations all their own. Chanute never relinquished his belief that a practical flying machine would maintain lateral stability on its own, not recognizing that actively managing lateral stability was essential for maneuvering. “It is possible to develop a flying machine which shall be automatically stable in the air,” he wrote in 1907, and “which will right itself up in every wind gust” [Octave Chanute, “Conditions of Success with Flying Machines,” American Magazine of Aeronautics, vol. 1, no. 1 (July 1907), 7-9]. Simine Short, From Locomotive to Aeromotive: Octave Chanute and the Transportation Revolution (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2011) is a thorough scholarly biography, long overdue. Readers inclined to make up their own mind about Chanute’s importance to the Wrights should read through the extensive correspondence between Wilbur and Chanute in McFarland, ed., Papers of Orville and Wilbur Wright. [↩]

- By 1928, when plans were laid for build a memorial atop Big Kill Devil Hill, the steady winds had moved the dune some 450 feet to the southwest. Today’s visitors are largely unaware that the Wright camp, carefully marked out close to the modern visitors center, is much farther from the hill than it was in 1900-1903 — or more accurately, the hill was much closer to their camp, since it is the hill that has moved. Sand dunes as much as forty feet high nearby, which the Wrights also used, were destroyed by a hurricane in 1932. The landscape of the park thus differs considerably from the barren sand hills that attracted the Wrights. [↩]

- Orville Wright to Katharine Wright, July 28, 1901, McFarland, ed., Papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright, 1: 71-76. [↩]

- First Rebuttal Deposition of Wilbur Wright, United States District Court, Western District of New York (1912). Complainant’s Record: The Wright Company vs. The Herring-Curtiss Company and Glenn Curtiss. p. 486. Some forty years later Orville told Fred Kelly that on the trip home in 1901 Wilbur had said “Not within a thousand years would man ever fly” (Kelly, Wright Brothers, 72). This more colorful formulation is frequently quoted, but Wilbur’s 1912 deposition is a more reliable source for the sentiment. [↩]

- Lorin’s daughter Ivonette remembered her father’s disappointment at this response and recorded the event in an unpublished reminiscence quoted in Crouch, Bishop’s Boys, 271. [↩]

- To its credit, and undoubtedly the amusement of readers, the Virginian-Pilot issued a lengthy correction on December 17, 2003, the one-hundredth anniversary of powered flight; Dayton Daily News, December 18, 1903. [↩]

- Statement by the Wright Brothers to the Associated Press, January 5, 1904, McFarland, ed., Papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright, 1 409-11. The statement was published as “Wright Flyer — A Report of the Late Tests Is Given by Messrs. Wright, Inventors of the Machine,” in the Dayton Press, January 6, 1904. The statement was circulated by the Associated Press and appeared in several newspapers on and after January 6. This report circulated widely but did not dispel misunderstanding. The New York Herald Magazine, January 17, 1904, described the Wright flyer as a balloon. [↩]

- Bishop Milton Wright’s Diary, May 23-26, McFarland, ed., Papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright, 1: 436; Wilbur Wright to Octave Chanute, May 27, 1904, McFarland, ed., Papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright, 1: 437-38. Twenty-five feet was the bishop’s estimate. Other sources put the distance at thirty and sixty feet. Wilbur told Chanute the flyer rose six feet off the ground. [↩]

- Luther Beard, quoted in Fred Kelly, The Wright Brothers, 139; the later visitor was Amos Root; see note 14 below. [↩]

- Amos Root, “Our Homes,” Gleanings in Bee Culture, vol. 23, no. 1 (January 1, 1905), 36-39; Amos Root, “The Wright Brothers’ Flying-Machine,” Gleanings in Bee Culture, vol. 23, no. 2 (January 15, 1905), 86-87. [↩]

- Wilbur Wright Diary F, October 5, 1905, McFarland, ed., Papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright, 1: 514. [↩]

- Wilbur Wright to Carl Dienstbach, November 17, 1905, Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology, Smithsonian Institution; Capt. [Alfred] Hildebrandt, “The Wright Brothers Flying Machine,” American Magazine of Aeronautics, vol. 2, no. 1 (January 1908), 13-16; Carl Dienstbach, “The Perfect Flying Machine,” The American Aeronaut, vol. 1, no. 3 (January 1908), 3-11. [↩]