The Wilderness is a rather ordinary looking woodland, but what happened there in May 1864 changed the course of our Civil War and the shape of our history. Nearly a century ago the federal government included parts of the Wilderness battlefield in Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park, but despite the best efforts of the National Park Service and preservationists, much of the battlefield is not protected. The battlefield is now threatened by a real estate development that would destroy the rural character of the area, overwhelm the park with traffic, and surround it with twenty-first century sprawl. If the development moves forward, the north side of the Wilderness battlefield will be destroyed.

A developer wants to cover 2,600 acres of open space — that’s four square miles, an area roughly the size of Lower Manhattan — with residential and commercial buildings, retail distribution warehouses, and industrial data centers. The data centers would consist of huge windowless buildings as much as eighty feet high and would consume vast amounts of water and electricity. “Wilderness Crossing” — the developer’s name for the project — would include as many as five thousand homes and the retailers to support thousands of residents. It would be, in effect, a new town on the boundary of a national park. Since the land wasn’t zoned for this kind of use, the developer asked the Orange County Board of Supervisors to rezone it.

Local residents — nearly all of them, it seems — oppose the plan, some because they care about the battlefield but most because they believe it will diminish the quality of everyday life. Environmental organizations, led by the Piedmont Environmental Council, oppose the development because it would destroy open space, stir up toxic waste from nineteenth-century gold mining, pollute the Rapidan River, dramatically increase demand for electricity and water, and add thousands of vehicles to overburdened roads. Preservationists, led by the American Battlefield Trust, oppose the development because it would compromise the integrity of the Wilderness battlefield. “We simply cannot allow this potentially catastrophic impact to occur,” says David Duncan, president of the American Battlefield Trust, “when better planning and thoughtful consideration could preserve such a vital and irreplaceable historic site.”

The development would bring thousands of cars and commercial traffic to Route 3 between the Rapidan River and Fredericksburg (about which the supervisors of neighboring Spotsylvania County have expressed alarm). Thousands of new residents at Wilderness Crossing would mean dozens of more gas stations and fast food outlets and more strip development between the Wilderness and Fredericksburg. The consequences for the Chancellorsville battlefield, which lies between the two, would be disastrous.

Wilderness Crossing would cover most of the land on the north (right) side of Route 3 in this aerial view. The boundary of Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park is on the south side of the highway. Union breastworks extended across the road here. Courtesy American Battlefield Trust

Wilderness Crossing would also spur development along Route 20 on the west side of the Wilderness battlefield, where Union troops briefly broke the Confederate lines before the Confederates mounted a successful counterattack. The site of that action lies on the western boundary of the park and much of it is outside the park. The American Battlefield Trust has acquired some of this land, but most of remains in private hands and would be attractive to developers if Wilderness Crossing is built.

The plan for Wilderness Crossing takes this into account. The developer proposes the state move Route 20, the historic Orange Turnpike and an axis of the battle, to better serve dramatically increased traffic crossing the battlefield on its way to Wilderness Crossing. They would shift the intersection of Route 20 and Route 3 to the west, which would require changing the historic path of the Orange Turnpike through the eastern side of the battlefield park. This should be a non-starter for the National Park Service, but political pressure would undoubtedly be put on the park service to accommodate the development.

The rezoning request was taken up by the Orange County Board of Supervisors on April 25, 2023. Every one of the dozens of people who spoke at the meeting opposed the project and asked the supervisors to reject the request. The supervisors nonetheless voted 4-1 to rezone the land. This was the largest single zoning change in the county’s history and was accomplished at the first public board meeting at which the application was considered. The approved application differs considerably from the proposal discussed by the county planning commission a few weeks earlier and includes a five-fold increase in the amount of industrial data center and warehouse space, which went from five million square feet to thirty million square feet without public disclosure, appropriate evaluation, or open discussion.

“Wilderness Crossing” would bury four square miles of battlefield land, woodlands, and riverfront under asphalt, concrete, and twenty-first century sprawl. Courtesy Piedmont Environmental Council

The American Battlefield Trust, the Central Virginia Battlefields Trust, Friends of Wilderness Battlefield, and local residents filed a lawsuit in November 2023 to overturn the zoning decision, citing major irregularities in the approval process they contend violate Virginia law. The American Battlefield Trust is appealing for financial support for the litigation and intends to pursue every available strategy to protect the battlefield. Opponents of the development have formed the Wilderness Battlefield Coalition, which includes the Cedar Mountain Battlefield Foundation, the Coalition to Protect America’s National Parks, Historic Germanna, Journey Through Hallowed Ground, the National Parks Conservation Association, Preservation Virginia, the Piedmont Environmental Council, and the National Trust for Historic Preservation. In May 2024 the National Trust for Historic Preservation named the Wilderness battlefield one of the eleven most endangered historic places in the United States, focusing national attention on the threat.

This fight is very similar to the current struggle over the future of the Manassas battlefield, which data center developers want to hem in with the world’s largest computer processing facility. Both proposals involve thousands of acres. County supervisors in both cases support the developers because they cannot resist the promise of increased tax revenue and underestimate the added costs of providing roads, schools, and the entire range of government services to the thousands of new residents the development will attract. In growing regions county officials are often more concerned about these imaginary people — people who don’t live in their jurisdiction yet and who didn’t elect them — than serving the interests of their constituents, the people who live in their counties now. Many of those constituents are hostile to sprawl.

Short-sighted county officials also fail to recognize the value of historic preservation to their local economy. Land devoted to battlefield parks is taken off the property tax rolls, but those same parks attract visitors who spend millions of dollars and support local businesses that pay taxes, all without the costs associated with massive developments. And choosing preservation is not an either-or proposition. Orange County has plenty of space for development that won’t compromise the national park.

Mark Johnson, chairman of the Orange County Board of Supervisors who voted to rezone the land, doesn’t seem to understand any of this. “I’m not sure how many thousands of acres are necessary to memorialize a battlefield,” he says. If he’s genuinely puzzled by this question he shouldn’t have acted in such haste.

The goal is not to “memorialize a battlefield.” It’s to memorialize a decisive moment in American history and the thousands of Americans who fought in one of our most terrible battles. To achieve that goal we have to preserve the scene of the battle and use the surrounding land in a way that’s compatible with understanding and appreciating what happened there.

Everything to Lose

Chairman Johnson’s uncertainty may be feigned — he may prefer warehouses and industrial data centers to national parks — but it reflects a common failure to grasp the importance of the Battle of the Wilderness.

It was a battle many preferred to forget. It was fought in a remote and inhospitable area — a Confederate staff officer called the Wilderness a “repulsive district.” None of the famed Civil War photographers followed the armies into the Wilderness and documented its scenes. The first photographers reached the battlefield after the war and could find little in the tangle of burnt-over second growth scrub to photograph except unburied skeletons. The battle stirred memories of unrelieved horror among many of its veterans, and relatively few returned to the Wilderness to reminisce after the war. Neither side celebrated it as a victory. For many of its generals the Wilderness was a battle of lost opportunities. It was not a battle of courtly heroics writers could romanticize. And over the battlefield looms the memory of Ulysses S. Grant, celebrated as the victor of the war in his own time but regarded for much of the last century as a second-rate soldier who drank too much and sent tens of thousands of young men to their deaths in a callous war of attrition that smothered the Confederacy under a mountain of corpses.1

The Wilderness battlefield challenges our imagination. It offers no sweeping vistas, no hilltops or ridgelines held against great odds, no fabled wheat field, peach orchard, stone bridge, or sunken road. The Wilderness is not an elegant, manicured battlefield park littered with monuments like Gettysburg or Antietam, vast outdoor memorials on which earlier generations imposed their ideas. The Wilderness is a simple woodland with scattered clearings, the battle lines marked by the remains of hastily constructed breastworks. But this is its peculiar value for us. Its landmarks are subtle. In place of sweeping vistas and soaring memorials it offers us the opportunity to consider the battle in our own way. This is also what makes it peculiarly vulnerable to the ambitions of developers and the indifference of public officials, to whom it looks like just another battlefield and not one of very great importance.2

To appreciate the Wilderness battlefield we need to understand what made the battle so important and how the battlefield reflects that importance in a way that compels us to preserve it. To grasp its importance we have to view the battle from the perspective of the men who risked the future of the United States on the outcome.

The Civil War had been going on for three years when the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia met in the Wilderness. In Virginia the two sides were about where they were when the war began, having churned through many thousands of young lives. For all the courage, suffering, and sacrifice of those years those armies had accomplished nothing of any military consequence except prolonging the war. In hindsight we imagine the Union victory at Gettysburg in July 1863 as the turning point that led inevitably to Union victory in the war. But it did not seem so to contemporaries and they were right.

War weariness was growing in the North. Recruiting had faltered and Lincoln’s government had turned to the draft, prompting riots in New York City that left 120 people dead and thousands injured. Defeat, corruption, and the mounting cost of war had blunted patriotic enthusiasm. Factions in the Republic Party were aiming to replace Abraham Lincoln in the upcoming election. Peace Democrats, arguing that the war was an expensive failure and that abolitionists had turned it into a misguided crusade for black equality, were gaining strength. Another costly defeat in Virginia — another Fredericksburg or Chancellorsville — and demands for an armistice might have become irresistible.

The Union had run out of opportunities to lose major battles in Virginia without losing the war. Lincoln understood what was at stake. In March 1864 he gambled and promoted Ulysses S. Grant, the victor of Vicksburg and Chattanooga, and gave him command of all of the Union armies. Grant replaced Henry Halleck, who like Grant had made his reputation in the war’s western theater but turned out to be a plodding administrator, Lincoln finally concluding that Halleck was nothing more than “a first-rate clerk.” George McClellan had found Halleck “hopelessly stupid” and resented being subordinated to him. That the senior generals of the Army of the Potomac, a group of distinguished, urbane Regular Army officers who had risen under McClellan, would accept subordination to Grant was not at all assured. They would follow his orders, of course, but it was not clear they would trust his leadership or that he would value their abilities.3

Ulysses Grant sat for this portrait when President Lincoln promoted him to command of the armies. A few days later Richard Henry Dana, a New England lawyer, encountered Grant in the lobby of the Willard Hotel. He described Grant as “an ordinary, scrubby-looking man” with “a look of resolution, as if he could not be trifled with.” Library of Congress

They were immediately put to the test. Too restless to manage the war from an office in Washington, Grant decided to make his headquarters with the Army of the Potomac, assuring its commander, George Gordon Meade, that he would leave army administration and tactical oversight to him. Grant harbored doubts about the fighting spirit of the generals of the Army of the Potomac, but he had little time to assess much less replace them in the few weeks remaining before the army resumed active campaigning.

Many of Meade’s officers were equally suspicious of Grant, whose western victories, they said, had come against small, poorly led Confederate armies. Grant may have overcome John Pemberton and Braxton Bragg, but Pemberton and Bragg were not Robert E. Lee. “The feeling about Grant is peculiar,” Capt. Charles Francis Adams, Jr., wrote to his father from Meade’s headquarters, “a little jealousy, a little dislike, a little envy, a little want of confidence — all in many minds and now latent.” Theodore Lyman, an aide on Meade’s staff, was more generous. Grant, he wrote, was “a man of a good deal of rough dignity; rather taciturn; quick and decided in speech. He habitually wears an expression as if he had determined to drive his head through a brick wall, and was about to do it.” Lyman concluded that Grant “is the concentration of all that is American.” As soon as the roads dried out Grant intended to cross the Rapidan and Rappahannock and confront Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia. Only then would the army learn the strengths and weaknesses of its new leader.4

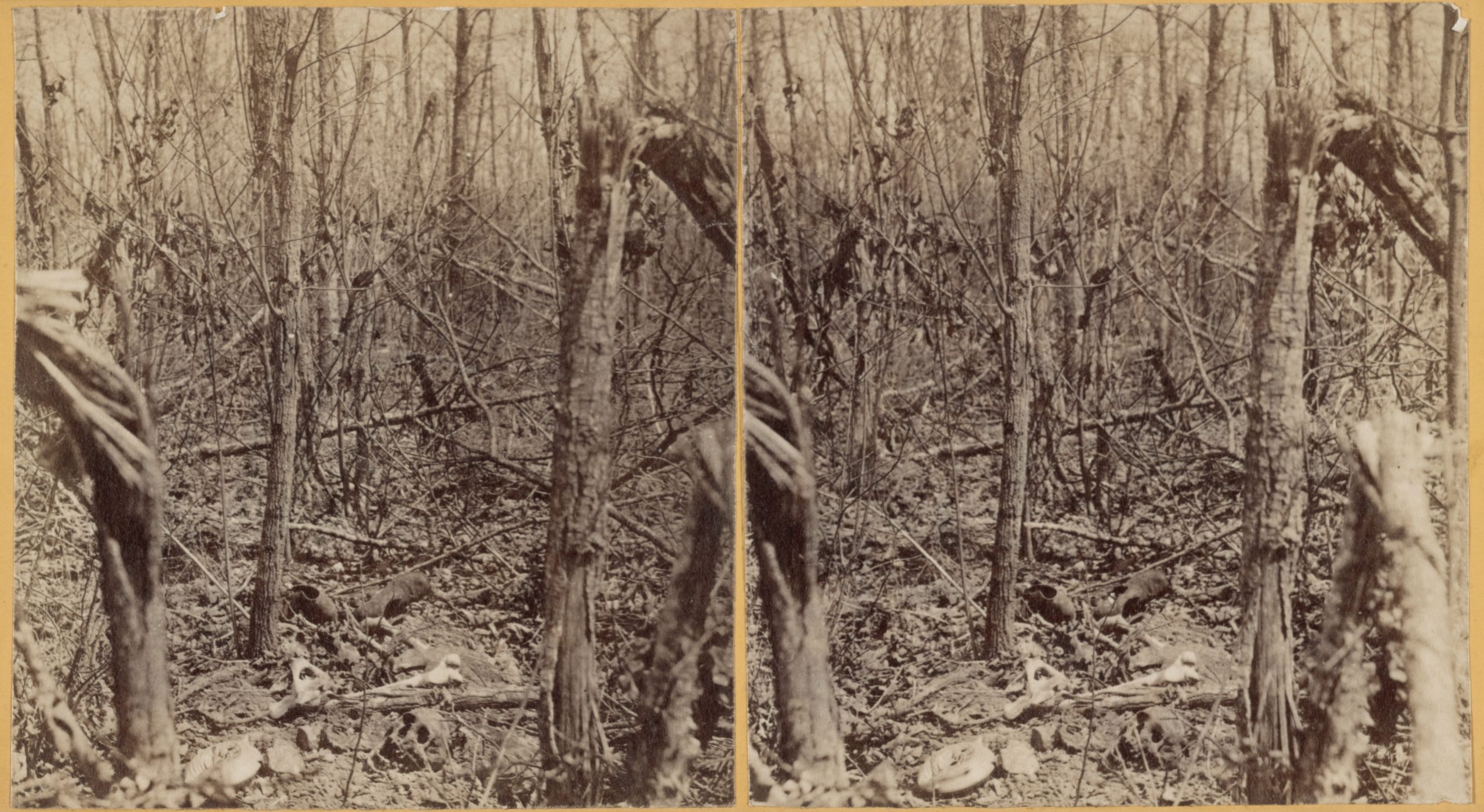

Contemporary photographs of the Wilderness battlefield depict the dense scrub and underbrush in which the battle was fought. This stereoscopic photograph was taken near the Orange Plank Road in 1865 by George O. Brown. The skeleton in the foreground was probably the remains of a Confederate soldier. Burial parties had recently gone over the area to collect Union remains. Library of Congress

Neither Grant nor Meade had any intention of fighting in the Wilderness, a dense tangle of spindly trees, briars, and underbrush extending south of the Rapidan and the Rappahannock for eight to ten miles. The Wilderness was crossed, east to west, by the Orange Turnpike and the newer Orange Plank Road, but it was a difficult place to maneuver and a harder place in which to fight. The Union army’s advantage in numbers counted for little in woods cut by narrow roads and the weight of its artillery was of small value in a forest. The Army of the Potomac had learned the disadvantages of operating in the Wilderness in the 1863 Battle of Chancellorsville, when the Confederates used the deep woods to mask a flank attack that crumpled the Union right and forced an inglorious retreat back across the Rappahannock.5

Grant and Meade aimed to push through the woods and into the more open country to the south where Lee was certain to bar the road to Richmond. They didn’t count on Lee moving swiftly to attack the Union army in the woods, despite Lee’s preference for taking the war to his opponents. It was a stunning miscalculation that could have cost the Union the war.6

“as if the earth had swallowed them”

With everything at risk, the Army of the Potomac crossed the Rapidan on May 4. It consisted of three large corps — the Second Corps under Winfield Hancock, the Fifth under Gouverneur Warren, and the Sixth under John Sedgwick. They were veteran general officers who had served with the Army of the Potomac since early in the war. The Ninth Corps, under Ambrose Burnside, was attached to the army but answered directly to Grant, a clumsy arrangement owing to the fact that Burnside, who had commanded the Army of the Potomac in the Fredericksburg debacle, outranked Meade. Burnside’s corps included a division of untried black troops — the first to serve with the Army of the Potomac — and a large proportion of conscripts, new recruits, and men who had spent the war on garrison duty. Not much weight could be put on the its shoulders and it crossed the river last, guarding the supply train.

That night the army was arrayed along the road from Germanna Ford east to the old Chancellorsville battlefield, where some of the men spent the night among unburied dead. The Fifth Corps made camp on land where the developer proposes to build Wilderness Crossing. A supply train crossed the Rapidan where the developer proposes to build massive data centers and the army’s medical service set up its supply depot on the property. Grant congratulated himself on getting across the Rapidan unopposed, not appreciating that Lee was unlikely to contest river crossings that would leave his opponent spread out and vulnerable.7

Edwin Forbes made this sketch of the trailing units of the Army of the Potomac crossing the Rapidan at Germanna Ford on May 5. Smoke rises on the horizon from the fighting on the Orange Turnpike. Library of Congress

On the morning of May 5 the Fifth Corps was already on the move when Warren learned that Confederate troops were marching up the Orange Turnpike from the west. “I do not believe Warren ever had a greater surprise in his life,” wrote one of his staff. Warren ordered division commander Charles Griffin to attack the enemy “and see what force he has.” General Griffin passed the assignment to a brigade commander who dispatched two regiments down the turnpike to investigate. The twenty-eight-year-old colonel of the Eighteenth Massachusetts, Joseph Hayes, promptly deployed four companies in a skirmish line across a clearing called Saunders Field, which straddled the turnpike.8

The chain of authority from corps commander to private ended on this particular morning with Charles Wilson, a seventeen-year-old Massachusetts farm boy who had enlisted in December. His captain put him into the skirmish line. In Saunders Field the skirmishers encountered the leading element of Richard Ewell’s corps of Lee’s army. Charles Wilson was killed, his death notable only because he was the first to die. Many more Charles Wilsons would die that day, and the next, with no notice at all. The skirmish line pulled back and Hayes reported to Griffin that the enemy had arrived in force and was building breastworks on the west end of the clearing. This intelligence, paid for with the life of a seventeen-year-old farm boy, reached Meade, who ordered Warren’s corps to attack immediately. Grant — who was back near Germanna Ford — urged Meade to attack without giving the Confederates time to complete their defenses.9

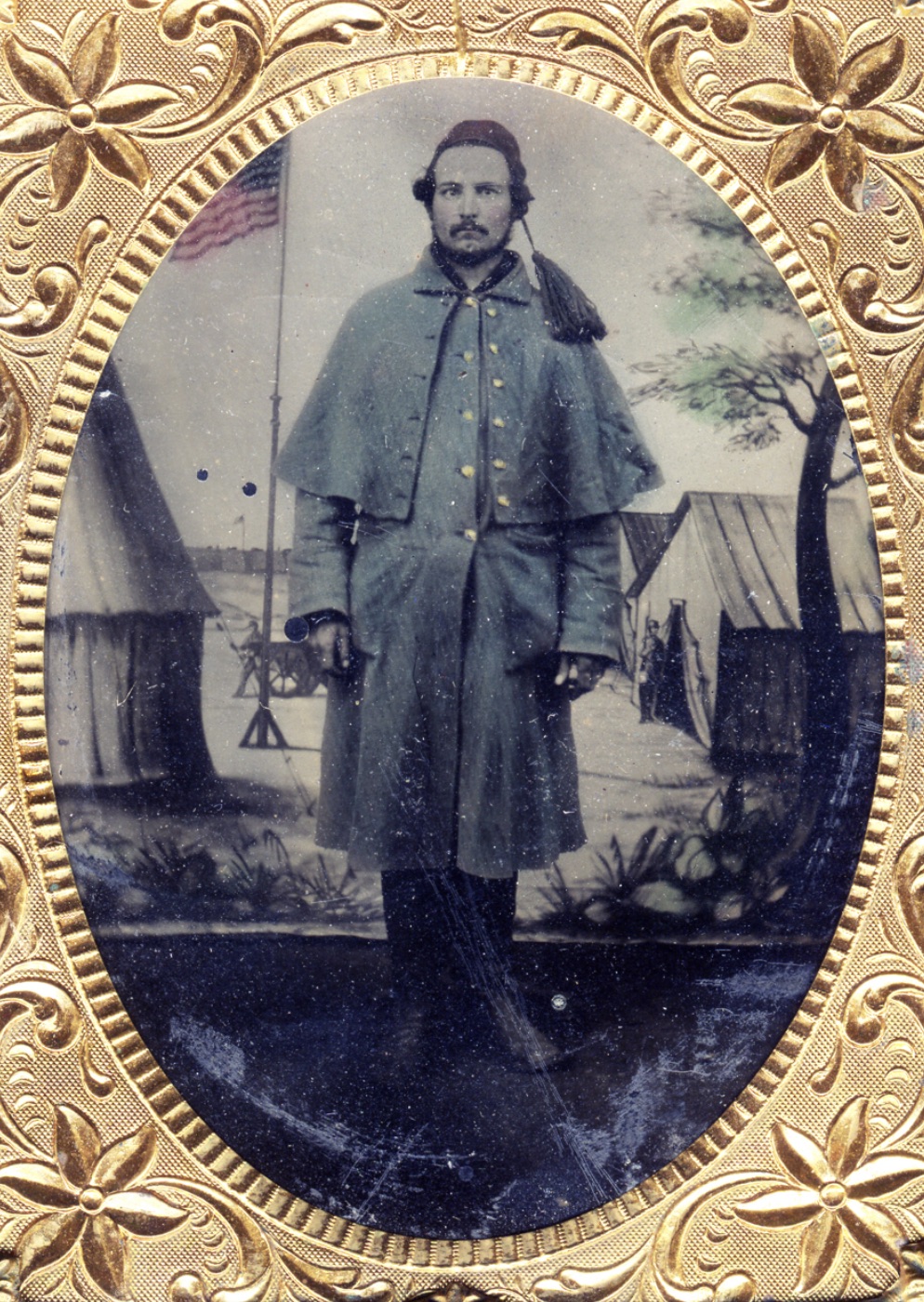

Henry Rae Dunne was a compositor at New York City newspaper when he was drafted in September 1863 and assigned to the veteran 140th New York Infantry. In his last letter home, written on April 29, he promised to send his three-year-old daughter a leaf from Virginia. He was wounded in Saunders Field on May 5 and either died on the battlefield or was taken prisoner and died in captivity. He never returned home. Collection of Paul Stokes.10

It took Warren’s corps until early afternoon to get into position, by which time Grant had joined Meade at his headquarters on a rise near the junction of what is now Route 3 and Route 20, facing the Wilderness Crossing site. There, Lyman wrote, Grant “took his seat on the grass, and smoked his briarwood pipe, looking sleepy and stern and indifferent.”11

He was, in fact, growing irritated and impatient. Whatever inclination he may have had not to interfere in the tactical dispositions of the Army of the Potomac was quickly evaporating. He made his displeasure known to Meade and in the process questioned the bravery of Meade’s army. Meade in turn said “unpleasant things” to Warren, whose headquarters was nearby. When Griffin urged Warren to delay the attack until Sedgwick’s Sixth Corps came up to support his men in the woods north of Saunders Field, Warren refused.12

The attack went forward around one that afternoon. The men of the 140th New York, distinctive in the baggy red pants and short blue jackets of the zouaves, were near the front. Captain Porter Farley remembered that the regiment did not slow until it reached the edge of the woods on the west side of Saunders Field, expecting to meet the Confederates with bayonets, only to find that the enemy had retreated a few yards into the undergrowth. The New Yorkers fired and advanced, but found itself without support on its right. The Virginia troops in their front got around their flank and raked the Union line.

“The regiment melted away like snow,” Farley wrote. “Men disappeared as if the earth had swallowed them. Every officer about me was shot down.” Among the wounded was Colonel Hayes of the 18th Massachusetts, who managed to get back to the Fifth Corps hospital, his face covered with blood. Ewell’s corps drove the disorganized attackers back across Saunders Field and through the woods to the east.13

When the attack was over Griffin rode to headquarters to vent his frustration. “Stern and angry,” according to Lyman, Griffin announced that he had had driven the enemy, but the divisions on either side had failed to keep up and he had been outflanked and forced to retreat. He blamed Warren for the debacle. Grant’s chief of staff John Rawlins was stunned by Griffin’s insubordination and urged Meade to arrest him. Grant asked Meade “Who is this General Gregg?” adding “You ought to arrest him.” Meade, though typically temperamental, responded gently, “It’s Griffin, not Gregg; and it’s only his way of talking.”14

The attack accomplished nothing except to expose discord and dysfunction in the Union command. Grant had come to the Army of the Potomac, wrote a member of Warren’s staff, “with an impression that in many of its engagements under McClellan, Pope, Hooker, and Meade, it had not been fought to an end.” The events of May 5 seemed, to Grant, to confirm this suspicion and led him to take more active control of Meade’s army.15

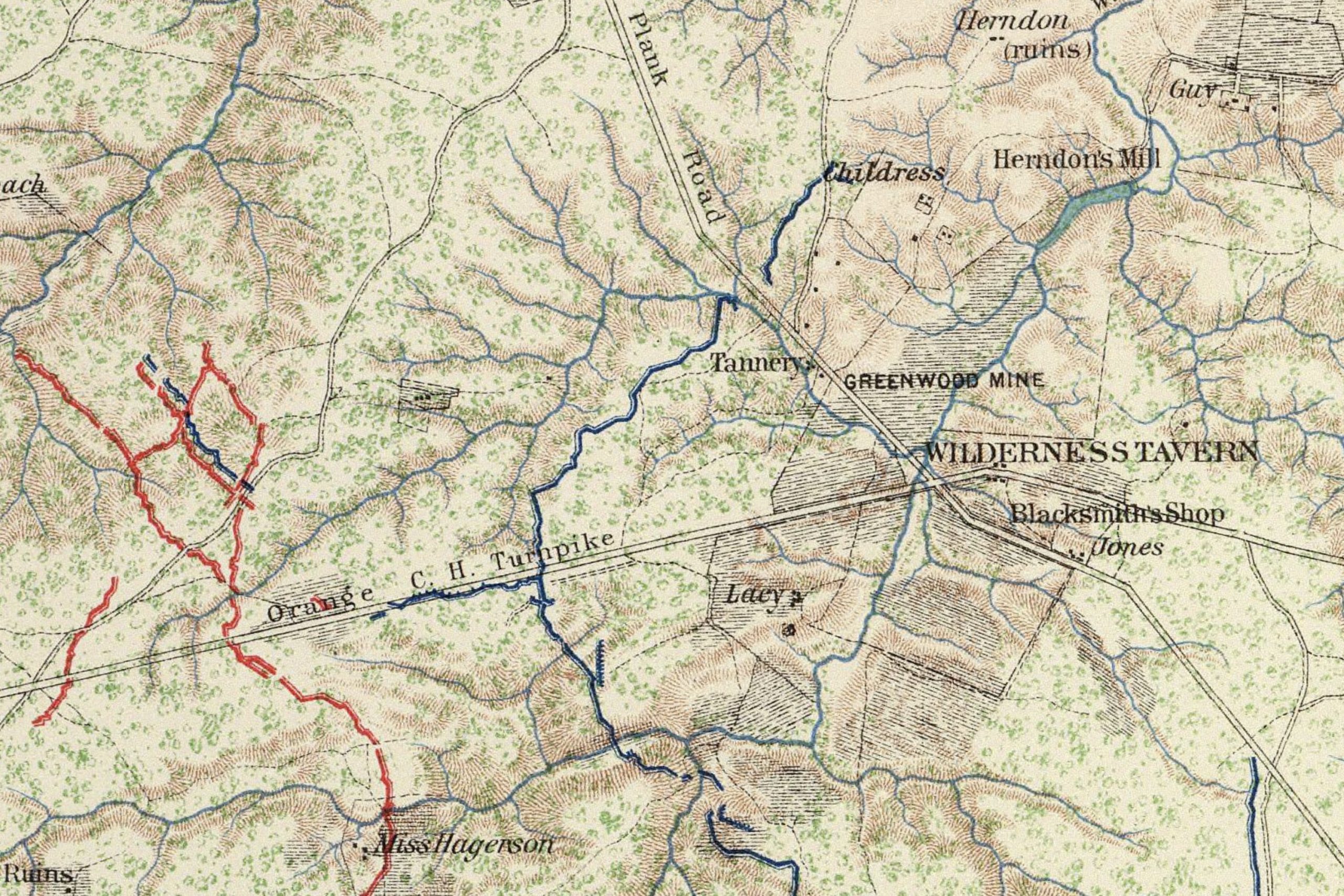

The Battle of the Wilderness began on May 5 in Saunders Field on the Orange Turnpike, the open space at middle left just to the east of the Confederate lines, which are marked in red on this U.S. Army map. Some of the heaviest fighting took place along the Orange Plank Road, which cuts diagonally across the map at lower right, culminating in savage fighting for the Union breastworks lining Brock Road on May 6. At the end of the battle a Confederate attack on the Union right north of the Orange Turnpike forced the Army of the Potomac to withdraw to new lines extending north across the Germanna Plank Road, at the top of this map. Wilderness Crossing would be built there, on the northern part of the battlefield close to the site of Grant’s headquarters. Leventhal Map Center, Boston Public Library

“unutterable horror”

The attack on the turnpike was a costly disappointment, but by the time it was over Grant and Meade had a more pressing challenge some three miles to the south. Union cavalry had encountered the leading units of A.P. Hill’s corps of Lee’s army on the Orange Plank Road in the morning. In response Meade and Grant dispatched George Getty’s division of Sedgwick’s corps to hold the intersection of the Orange Plank Road and Brock Road, the main route southeast toward Spotsylvania Court House, until Hancock’s corps joined them. Getty parried Hill’s men until early afternoon, when two divisions of Hancock’s corps took up a position along the Brock Road.

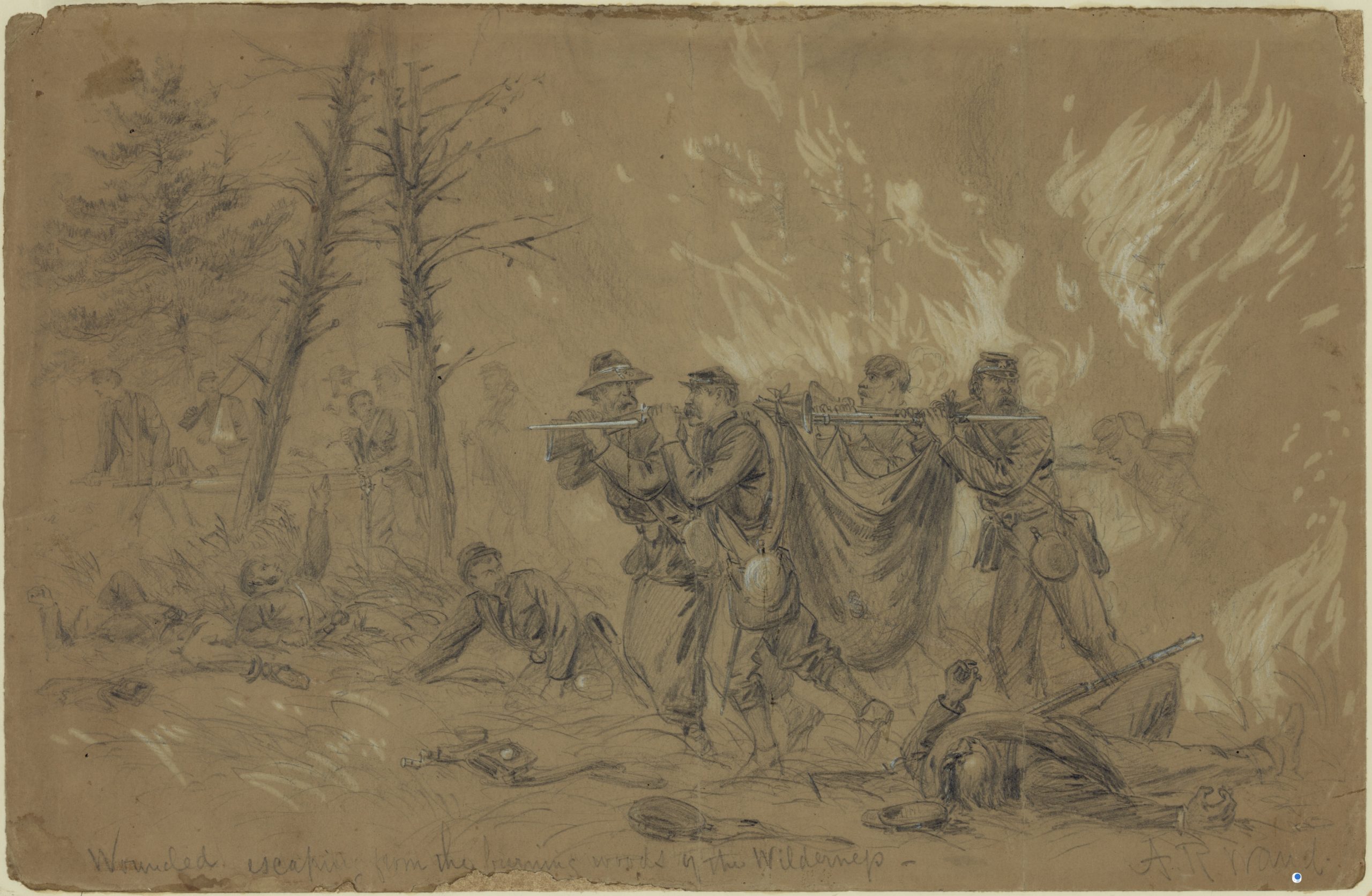

Hancock then launched an attack that continued through the afternoon. Most of the fighting took place in the tangled woods on either side of the plank road. Hopelessly snarled in the scrub, units lost cohesion and fired blindly. “There were features of the battle,” wrote Grant’s aide Horace Porter, “which have never been matched in the annals of warfare.” Smoke filled the tangled woods and reduced visibility to a few yards. Officers gave orders based more on sound than sight except when the flash of enemy volleys made it plain, for a moment, which direction to fire. “All circumstances seemed to combine to make the scene one of unutterable horror.” Gunfire soon set the woods on fire. Ammunition wagons exploded, killing men and spreading flames in every direction. The smoke of forest fires combined with the smoke of battle. Wounded men unable to crawl out of the flames suffocated or burned to death. Burnt corpses were scattered through the woods. Hancock managed to push Hill back, but suffered horrifying losses in some of the most confused fighting of the war.16

The woods beyond the intersection of the Orange Plank Road (running west toward the horizon) and Brock Road were the scene of some of the most brutal combat of the Civil War. This area had changed very little in the twenty-three year between the battle and 1887, when William H. Tipton made this photograph. J. Brainerd Hall of the 57th Massachusetts Infantry was shot on May 6 while fighting near this point. He languished overnight in a field hospital and four days later reached a makeshift hospital in the Methodist Church in Fredericksburg, where he was nursed by Clara Barton. Hall returned to the Wilderness with a group of Massachusetts veterans in 1887 and acquired this copy of Tipton’s photograph as a keepsake.17 Virginia Museum of History and Culture

Nightfall ended the fighting for a few hours, but forest fires spread during the night, reaching wounded men trapped between the lines. A veteran of the 118th Pennsylvania wrote that “their shrieks, cries and groans, loud, piercing, penetrating, rent the air, until death relieved the sufferer, or the rattle of musketry, that followed the advent of the breaking morn, drowning all the other sounds in its dominating roar.”18

By nightfall on May 5, A.P. Hill’s Confederates on the Orange Plank Road were spent. Grant cannot have known this but he was inclined to press. He instinctively understood the importance of seizing and holding the initiative. He knew that Lee would take advantage of any opening and was determined not to give him one. From prisoners Union commanders learned that James Longstreet’s corps was expected by dawn. Grant ordered Hancock to attack at first light and break Lee’s right before Longstreet arrived. 19

Alfred Waud captured the horror of the fighting in the Wilderness in this drawing of Union soldiers rescuing a wounded comrade from the flames. Library of Congress

At 5 a.m. Hancock attacked Hill’s weary men and drove them down the plank road, the Confederates falling back in disorder. “So thick were the trees,” wrote William Hincks of the 14th Connecticut, “that it was difficult for men to advance and we could seldom see further than a few rods ahead.” Hancock’s men paused on the edge of a clearing to dress their lines before delivering a final, crushing blow. On the far side of the field a Confederate battery with twelve guns fired grapeshot to hold Hancock’s men at bay, but with their infantry support dissolving they could not hold their position for long.20

Longstreet’s corps arrived at that critical moment. His troops formed their line of battle in the stunted woods and dense undergrowth while Hill’s dispirited men passed through, disorganized, to the rear. Despite have been on the march since one in the morning Longstreet’s men advanced flawlessly. They brought the Union attack to a halt and drove Hancock’s stubborn veterans back. Longstreet then directed his adjutant, G. Moxley Sorrel, to take three brigades and hit Hancock’s line on its exposed left in the woods north of the plank road. Hancock said this attack “rolled me up like a wet blanket.”21

The flank attack reached the Orange Plank Road, but in the smoke and confusion of the moment Longstreet was wounded by fire from his own men. No one else understood the disposition of the Confederate troops so the attack paused while they were sorted out. This gave Hancock the opportunity to place his men behind breastworks along Brock Road.

The pause lasted until shortly after four in the afternoon, when the Confederates mounted an assault on the Union left on both sides of the Orange Plank Road, moving troops to within a hundred yards of the breastworks and opening a heavy fire. After half an hour the woods all around were ablaze and the log breastworks caught fire. The battle continued, Grant wrote, “our men firing through the flames” until they could no longer stand the heat and smoke. At one point the Confederates reached the breastworks and planted their flags but were driven back. Whole trees burned and came crashing down through the smoke, crushing men who were unable to see more than a few feet in any direction. In places the fighting was hand to hand. “It was as though Christian men had turned to fiends,” Porter remembered, “and hell itself had usurped the place of earth.” The Union line held — barely — but when Lee finally withdrew Hancock’s men were out of ammunition and too exhausted to counterattack.22

Before darkness fell Lee made a final bid to smash Grant’s army. The brigade commander on the extreme left of the Confederate line, John Brown Gordon, had discovered that the Union right ended in the woods north of the Orange Turnpike, completely exposed to a flank attack. Gordon had scouted the area before dawn and assured his division commander, Jubal Early, that such an attack would result “in the crushing defeat of General Grant’s army.” Early was just as certain that Gordon was wrong. Ewell refused to overrule Early and the day passed with little action on their front. Near sunset, with the armies deadlocked on the plank road, Lee learned of Gordon’s plan. He overruled Ewell and Gordon went crashing through the underbrush, driving the Union right in disorder and capturing hundreds of prisoners, including two brigadier generals.23

Confederate troops are barely visible through the trees in this Alfred Waud sketch of James Wadsworth’s division fighting near the Orange Plank Road on May 6. Wadsworth was mortally wounded during this action. Library of Congress

Reports of looming catastrophe reached Grant’s headquarters. Two staff officers reported that the entire Sixth Corps had been routed, and others claimed that Sedgwick and one of his division commanders had been captured. A general rode back to headquarters in a panic and warned Grant that “this is a crisis that cannot be looked upon too seriously. I know Lee’s methods well by past experience; he will throw his whole army between us and the Rapidan, and cut us off completely from our communications.”24

By then Grant had heard enough. For a moment he lost his usual composure and rose to his feet, saying, to every officer within hearing: “I am heartily tired of hearing about what Lee is going to do. Some of you always seem to think he is suddenly going to turn a double somersault, and land in our rear and on both of our flanks at the same time. Go back to your command, and try to think what we are going to do ourselves, instead of what Lee is going to do.”25

Grant calmly dispatched reinforcements to the point of attack and withdrew the army’s right all the way to the Germanna Plank Road. As the day’s fighting came to an end, the Union right rested on what will be the entrance to the Wilderness Crossing if the developer has his way.

In the final stage of the battle, Grant withdrew the right wing of his army to new fortified lines crossing the Germanna Plank Road, depicted in blue on this 1867 map prepared by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The army’s right flank, near the Childress house, rested on land where Wilderness Crossing would be built.

“Wild cheers echoed through the forest”

When dawn came on May 7 neither army advanced. The men were exhausted and their commanders recognized that they had asked all that they could expect. “More desperate fighting,” Grant later wrote, “has not been witnessed on this continent.” The woods continued to burn, filling the heavy air with smoke.26

In almost identical circumstances a year before the Army of the Potomac had retreated across the Rappahannock to recover and reorganize. In many respect it had been handled more roughly in the Wilderness than at Chancellorsville. Lee’s army had beaten in both flanks and held the ground in front. The casualties were appalling. Over seventeen thousand Union soldiers were dead, wounded, or missing, along with more than twelve thousand Confederates — totals only exceeded over three days at Gettysburg, in the ghastly two-day Battle of Chickamauga, and over the sprawling twelve-day Battle of Spotsylvania Court House. More Americans were killed at the Battle of the Wilderness than died in Normandy on D-Day.27

Renewing the battle in the woods could serve no useful purpose, but the Army of the Potomac had to move somewhere. Grant knew that if the army retreated it would have to pay the whole price of the Wilderness a second time. So without calling a counsel of war or seeking Meade’s counsel or indeed the advice of anyone, Grant made his decision — the most important decision of the Civil War.

Grant might have ordered a retreat from the Wilderness, but it was not in his nature. Richard Dana had sensed his determination, Theodore Lyman his apparent willingness to drive his head through a brick wall. James Longstreet had known Grant before the war — known him much better than the officers of the Army of the Potomac — and warned fellow Confederates before the campaign opened: “We must make up our minds to get into line of battle and to stay there; for that man will fight us every day and every hour until the end of the war.” Lee, who knew Grant not at all, recognized when the Battle of the Wilderness was done that Grant would not retreat.28

Yet Grant’s nature did not determine the matter. He had to have the opportunity to decide as he did, and that opportunity was contingent on things that happened and did not happen during the battle. The Army of Northern Virginia might have routed the Army of the Potomac if Longstreet had not been wounded or if Ewell had sided with Gordon and Ewell’s corps had flanked the Union right while much of the Union army was engaged on the Orange Plank Road. If either or both of those things had happened the Army of the Potomac would have retreated in confusion and the future of the war and everything to follow might have been very different. None of those thing had happened.

Shortly after dawn Grant wrote out orders for the army to move south, toward the more open ground around Spotsylvania Court House. Grant understood that this would result in more battles in which the cost in lives would be terrible but if the army paid that price it would only have to pay it once. The march was to begin at dark, when the Confederates would be less likely to detect it and attack the army while it was pulling out of the lines.

Ordinary soldiers knew nothing of these plans and waited all day behind breastworks, most expecting an order to retreat, as their army had done after so many battles. Grant remained at his headquarters near the intersection of the Orange Turnpike and the Germanna Plank Road most of the day. Then late in the afternoon he rode to the Orange Plank Road and on toward Hancock’s headquarters, where he planned to wait while the troops marched past.

It was dark when he reached Brock Road, where the day’s fighting had been savage and the smoke from the smoldering woods hung heavy in the air. Hancock’s men watched as Grant and his staff rode by their lines. He had been with the army only a few weeks, and most of the men had never seen him or had only seen him from afar, but soldiers recognized him, and word passed through the lines that the army was not retreating after all. They were pulling out, the men learned, but the general who had led them into the Wilderness had ordered the army to march south, toward the Confederate capital. Soldiers forgot their exhaustion and rushed to the road from all sides to celebrate. Grant paused, Horace Porter recalled. “Wild cheers echoed through the forest,” as men used to retreat pressed forward, clapping and calling out to the general. Men tossed their hats in the air. Torches lit the scene, which became all at once a triumphal procession.29

Edwin Forbes captured the moment when the veterans of the Army of the Potomac, marching through the haze of the burning forest, cheered Grant for leading them south. Library of Congress

From that moment until Lee surrendered his army at Appomattox on April 9, 1865, the armies fought every day. And every day young men died, on some days just a few, on others many thousands, until Lee’s army had no more fight in it. Among the dead of that terrible year were men who crowded the road that night to cheer before they marched toward Spotsylvania Court House.

They left the Wilderness battered and crowded with the dead. “I have never before seen woods so completely riddled with bullets,” a Confederate doctor wrote to his wife. “The dead Yankees are everywhere.” The northerners, he said, “had not taken the time to bury their dead except behind their breastworks.”30 Burial parties returned to the battlefield at the end of the war and collected the skeletons of the Union dead and buried them in two temporary cemeteries, one on the turnpike and the other on the plank road. The army later moved them to the national cemetery on Marye’s Heights in Fredericksburg. Many of the dead were never found. The Wilderness still holds their remains.

Despite all the suffering and sacrifice it is hard to be sentimental about the Battle of the Wilderness. It has too much in common with Verdun and the Somme, where men died in the mud, winning nothing, in titanic battles without heroes. For most of the twentieth century we didn’t want to imagine our wars that way. Our impulse was to romanticize, and we decided the important battles were the most romantic — Jackson standing like a stone wall at Bull Run, the sacrificial drama of Pickett’s Charge — with moments to inspire sculptors, painters, poets, and filmmakers.

The horrors of modern war have weakened the hold of romance on our imagination. Glory no longer stirs us as it once did. Much as we admire courage and devotion to duty we dwell on body counts. The Wilderness is a reminder of the awful brutality and terror of war and for that reason alone the battlefield ought to be carefully preserved. The lessons the Wilderness battlefield offer are too important to be sacrificed to commercial profit.

Preserving our Civil War battlefields is ultimately an act of patriotism. It flows from an unselfish love of country and a sense of kinship with the men and women of our nation’s shared past. That sense of kinship does not depend on a family tie to the Civil War. It can be felt by anyone who has embraced the ideals that define our national identity — independence, liberty, equality, natural and civil rights, and responsible citizenship — and who understand that terrible costs have been paid to secure them.

Critics of battlefield preservation say that it stands in the way of progress — by which they mean the bulldozer — and that we cannot live in the past. They fail to grasp that history lives in the present, in how we understand ourselves and our own time. Our identity is tied together by ideas and the historical experiences that shaped them. There is a little bit of Lexington Green and Antietam and the Wilderness in each of us, and preserving them offers all of us opportunities to reflect on our relationship to the ideas, people, and events that fill them with meaning. On a battlefield history is not an abstraction. When a battlefield is gone — buried under asphalt and concrete or compromised by traffic and strip shopping centers, warehouses, or data centers — our ability to understand ourselves is diminished.

Notes

- James Longstreet’s adjutant G. Moxley Sorrel called the Wilderness a “repulsive district” in his Reminiscences of a Confederate Staff Officer (New York: The Neale Publishing Company, 1917), 231; William A. Frassanito, Grant and Lee: The Virginia Campaigns, 1864-1865 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1983), 47, explains that none of the wartime photographers took photographs in the Wilderness, though Timothy O’Sullivan photographed the Army of the Potomac crossing the Rapidan on May 4, 1864; on the evolution of Grant’s historical reputation, see especially Joan Waugh, U.S. Grant: American Hero, American Myth (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013). Grant’s reputation as a military and political leader has risen in this century, thanks largely to the publication of The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, edited by John Y. Simon and his colleagues, and published by Southern Illinois University Press between 1967 and 2009. The books resting on this foundation include Brooks D. Simpson, Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph Over Adversity, 1822–1865 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2000), Ron Chernow, Grant (New York: Penguin Press, 2017), and the new annotated scholarly edition of The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant, edited by John F. Marszalek (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2017). [↩]

- John Auwaerter and James Mealey, et al., Cultural Landscape Report for Wilderness Battlefield — Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park, Spotsylvania and Orange Counties, Virginia (Boston: National Park Service, 2021) is a marvelous guide, in rich detail, to the present state of the battlefield. Anyone interested in how the battlefield has changed since the war and how the park has evolved would do well to take a copy with them to the battlefield. Readers who want to learn more about the Battle of the Wilderness should begin with the opening chapters of Bruce Catton’s elegiac A Stillness at Appomattox (Garden City, New York: Doubleday and Company, 1953). The standard modern military history is Gordon C. Rhea, The Battle of the Wilderness, May 5-6, 1864 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1994), which focuses on strategy and tactics and is critical of blunders on both sides, supplemented by Gary W. Gallagher, ed., The Wilderness Campaign (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997). John Reeves, Fire in the Wilderness: The First Battle Between Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee (New York: Pegasus Books, 2021) is a graceful account that focuses more on the experience of the battle than strategy and tactics. A fine short account is Chris Mackowski, Hell Itself: The Battle of the Wilderness, May 5-7, 1864 (El Dorado Hills, California: Savas Beatie, 2016). The specialized atlas by Bradley M. Gottfried, The Maps of the Wilderness Campaign: An Atlas of the Wilderness Campaign, May 2-7, 1864 (El Dorado Hills, California: Savas Beatie, 2016), helps make the complex battle comprehensible. [↩]

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, eds., Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1999), [April 28, 1864], 191; George B. McClellan, McClellan’s Own Story (New York, Charles L. Webster & Company, 1887), 137. [↩]

- Charles Francis Adams, Jr., to Charles Francis Adams, May 1, 1864, Worthington C. Ford, A Cycle of Adams Letters, 1861-1865 (2 vols., Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company), 2: 126-28; Theodore Lyman to Elizabeth Russell Lyman, April 12, 1864, George R. Agassiz, ed., Meade’s Headquarters 1863-1865: Letters of Colonel Theodore Lyman from The Wilderness to Appomattox (Boston: The Atlantic Monthly Press, 1922), 81; TL to ERL, June 12, 1864, ibid., 156. Though a friend to Meade and attached to his staff as a volunteer aide, Lyman described Meade as “an abrupt, harsh man, even to his own officers.” TL to ERL, April 17, 1865, ibid., 359. Lyman was a civilian at heart to whom the competition for precedence and prestige among West Pointers was opaque, but his letters offer the insights of a sophisticated and thoughtful spectator. Richard Henry Dana, a wealthy New Englander lawyer who encountered Grant at the Willard Hotel on April 21, 1864, was not as generous but expressed similar conclusions. “He had a cigar in his mouth,” Dana wrote, “and rather the look of a man who did, or once did, take a little too much to drink.” He found Grant “an ordinary, scrubby-looking man, with a seedy look” but added that he had “a clear blue eye and a look of resolution, as if he could not be trifled with.” Dana visited Meade’s headquarters on April 26 and implicitly noted the contrast between Grant and his new subordinates, noting that “Meade and Humphreys [his adjutant general] are gentlemen — well-bred, courteous, honorable men, — and they set the tone of headquarters.” Charles Francis Adams, Richard Henry Dana: A Biography (2 vols., Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1890), 2: 271-72, 273. [↩]

- The region was desolate as early as 1732, when William Byrd rode over it and found “on either side continual poisen’d Fields, with nothing but Saplins growing on them.” John Spencer Bassett, ed., The Writings of Colonel William Byrd of Westover in Virginia Esqr. (New York: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1901), 356. In the early nineteenth century what remained of the old growth forests had been cut over to make charcoal for iron furnaces and rough lumber for plank roads. [↩]

- Rhea, Battle of the Wilderness, 118; Lee, in fact, had been looking for a way to resume the offensive for three months, having written to Jefferson Davis on February 3: “The approach of spring causes me to consider with anxiety the probable action of the enemy, and the possible operations of ours in the ensuing campaign. If we could take the initiative and fall upon them unexpectedly we might derange their plans and embarrass them the whole summer” and suggested reinforcing Longstreet for an invasion of Kentucky or “forcing General Meade back to Washington, and exciting sufficient apprehension at least for their own position to weaken any movement against ours.” When Longstreet rejoined Lee the latter became Lee’s objective. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, series 1, volume 33 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1891), 1144. [↩]

- For the medical services on the Wilderness Crossing site, see Joseph Barnes, The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1870), 151-52. [↩]

- Rhea, Battle of the Wilderness, 99-101; Schaff, Battle of the Wilderness, 126-27. Meade’s failure to send cavalry south and west of the Wilderness to screen his army’s movements and discern Lee’s intentions was the reason he and his generals were surprised. See Rhea, Battle of the Wilderness, 110-12. [↩]

- “Report of Lieut. Col. William B. White, Eighteenth Massachusetts Infantry, of operations May 4-23 [1864],” August 1864, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, series 1, volume 36, part 1 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1891), 575-77. White asserted that Wilson was the first Union infantryman killed in the battle, which is probably correct. White does not place the action in Saunders Field, but Lt. Col. De Witt C. McCoy, Eighty-Third Pennsylvania, in his report of August 7, 1864, describes the skirmishers advancing “from the edge of an open field” (ibid., 588-89), which can only be Saunders Field; John J. Hennessy, ed., Fighting with the Eighteenth Massachusetts: The Civil War Memoir of Thomas H. Mann (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000), 234-35; Grant’s order to Meade was “If any opportunity presents itself for pitching into a part of Lee’s army, do so without giving time for disposition.” This order is commonly misquoted and misinterpreted as an order to attack impetuously, without careful preparation, when Grant plainly meant that the army should deny Lee’s troops the time to dispose themselves to receive an attack. U.S. Grant to G.G. Meade, 8:24 a.m., May 5, 1864, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, series 1, volume 36, part 2 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1891), 403. [↩]

- Dunne’s letters are among the thousands of Civil War letters transcribed and published online by William Griffing at Spared & Shared. [↩]

- Theodore Lyman to Elizabeth Russell Lyman, May 15, 1864, George R. Agassiz, ed., Meade’s Headquarters 1863-1865: Letters of Colonel Theodore Lyman from The Wilderness to Appomattox (Boston: The Atlantic Monthly Press, 1922), 91. Grant remained there throughout the battle, with only brief forays to nearby units. Andrew Humphreys, The Virginia Campaign of ’64 and ’65 (New York: Charles Scribner’s, 1883), 24. [↩]

- The authority for Grant disparaging the army and Meade’s exchange with Warren is William W. Swan, “Battle of the Wilderness,” Papers of the Military Historical Society of Massachusetts, vol. 4 [The Wilderness Campaign, May-June 1864] (Boston: Published by the Society, 1905), 119-63; the quoted passage is on p. 129. Swan was on the staff of General Ayres, one of Griffin’s brigade commanders. [↩]

- Farley’s manuscript account of the fight at Saunders Field is the Porter Farley Papers, Rundel Library, Rochester, New York. An edited version, “The 140th New York Volunteers: Wilderness, May 5th, 1864,” is in Blake McKelvey, ed., Rochester in the Civil War, The Rochester Historical Society Publications, vol. 12 (Rochester: Published by the Society, 1944), 237-44. A full version is available in Brian A. Bennett, ed., An Unvarnished Tale: The Public and Private Civil War Writings of Porter Farley, 140th N.Y.V.I. (Wheatland, New York: Triphammer Publishing, 2007). See also Brian A. Bennett, Sons of Old Monroe: A Regimental History of Patrick O’Rorke’s 140th New York Volunteer Infantry (Dayton, Ohio: Morningside Bookshop, 1996). On the wounded Hayes, see Theodore Lyman to Elizabeth Russell Lyman, May 15, 1864, Agassiz, ed., Letters of Colonel Theodore Lyman from The Wilderness to Appomattox, 88. [↩]

- Agassiz, ed., Letters of Colonel Theodore Lyman, 91. Warren was privately fuming about having been forced to attack before he was ready. See Rhea, Battle of the Wilderness, 141, 172-73. [↩]

- Morris Schaff, The Battle of the Wilderness (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1910), 106. This was the first book-length treatment of the battle. Schaff returned to the battlefield while writing his book. It is written in an easy, conversational style, touched by a romantic spirit. [↩]

- Horace Porter, Campaigning with Grant (New York: The Century Co., 1907), 72-73. [↩]

- John Anderson, The Fifty-Seventh Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers in the War of the Rebellion (Boston: E.B. Stilling & Co., Printers, 1896), 57-60; Percy H. Epler, The Life of Clara Barton (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1915), 91-92. The photograph is in the collections of the Virginia Museum of History & Culture. [↩]

- Emory Upton alleged that Ewell’s Corps deliberately set fires north of the Orange Turnpike on the afternoon of May 5 to block the Union advance there; no conclusive evidence has been found that any of the fires were deliberately set. “Report of Brig. Gen. Emory Upton, U.S. Army, commanding Second Brigade,” September 1, 1864, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, volume 36, part 1 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1891), 665; [Survivor’s Association], History of the Corn Exchange Regiment, 118th Pennsylvania Volunteers, from their first engage at Antietam to Appomattox (Philadelphia, J.L. Smith, 1888), 403. [↩]

- Douglas Southall Freeman, R.E. Lee: A Biography, vol. 3 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1935) 280. Hill’s men rested overnight rather than improve their breastworks, which Lee expected to abandon when Longstreet arrived. ibid., 285. That prisoners had revealed that Longstreet was expected by dawn is documented in Humphreys, The Virginia Campaign of ’64 and ’65, 37. Humphreys was Meade’s chief of staff and in a position to know. [↩]

- Charles D. Page, History of the Fourteenth Regiment, Connecticut Vol. Infantry (Meriden, Connecticut: The Horton Printing Co., 1906), 235-316; Freeman, R.E. Lee, 3: 287; Hancock directed two of his divisions and one of Sedgwick’s in this assault. [↩]

- G. Moxley Sorrel, Recollections of a Confederate Staff Officer (New York: The Neale Publishing Company, 1917), 235-36; 287-92; James Longstreet, From Manassas to Appomattox: Memoirs of the Civil War in America (Philadelphia: L.B. Lippincott Company 1896), 568; Douglas Southall Freeman, Lee’s Lieutenants: A Study in Command, vol. 3 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1944), 360-68. [↩]

- Humphreys, The Virginia Campaign of ’64 and ’65, 47-49; Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant (2 vols., New York: Charles L. Webster & Company, 1885-86), 2: 201; Porter, Campaigning with Grant, 72-73. [↩]

- John Brown Gordon, Reminiscences of the Civil War (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1903), 243-61. Early insisted that Burnside’s corps was behind the Union right flank, which was wrong. Most of Burnside’s men had been committed to the fight on Orange Plank Road. Thus, Gordon wrote, “the greatest opportunity ever presented to Lee’s army was permitted to pass” (p. 261). His success in the short time before dark suggests what he might have accomplished if permitted to attack earlier in the day. Douglas Southall Freeman comes down on Gordon’s side; see Freeman, Lee’s Lieutenants, 3: 368-72. [↩]

- On the rumors reaching headquarters, see TL to ERL, May 17, 1864, Agassiz, ed., Letters of Colonel Theodore Lyman, 98. [↩]

- Porter, Campaigning with Grant, 68-70. Porter says the panicky officer Grant rebuked was a general but unfortunately doesn’t identify him. [↩]

- Grant, Personal Memoirs, 2:204. [↩]

- Battle casualty statistics should be used with care and awareness about how records were created and maintained. Grant’s staff included the casualties sustained on May 7, 1864, mostly by cavalry on the road to Spotsylvania Court House, in the losses of the Wilderness. But Rhea contends that some Union commanders consciously underestimated their losses. Rhea, Battle of the Wilderness, 435-36. By any measure the Battle of the Wilderness was one of the most terrible in our history. [↩]

- Porter, Campaigning with Grant, 46-47. Porter learned about Longstreet’s warning in a conversation with Longstreet “several years after the war.” [↩]

- Porter, Campaigning with Grant, 78-79. [↩]

- Dr. Spencer Welch to his wife, Cordelia “Corrie” Strother Welch, May 7 and 17, 1864, Spencer Glasgow Welch, A Confederate Surgeon’s Letters to His Wife (New York: The Neale Publishing Company, 1911), 93-96, 98; Welch was surgeon to the 13th South Carolina. His letters were compiled by his daughter Eloise Welch Wright (1874-1973). [↩]